For food historian and cookbook author, Joan Nathan, recipes need to be about more than just pretty food. What interests her, particularly at seder time, is how a recipe creates a connection to the past.

In all her work, and particularly her new cookbook King Solomon’s Table, Nathan is not just about the food itself, but about the stories behind it: who the people are who cook it and what it means to them, where they are from and how they come by their food traditions. Many of her recipes are not from professional cooks, though some are.

Rest assured of Nathan’s food world bona fides; she has won James Beard and Julia Child awards for her cookbooks and no less an authority than Alice Waters of Chez Panisse in Berkeley CA wrote the foreword. Nathan both researches recipes in archives (such as going to Oxford to see lists of ingredients that were found in the 8-12th centuries in the Cairo Genizah, as she told me in a recent interview at the Bread Furst bakery near her home in Washington DC) and visits individuals in their homes around the world to get their recipes as well as their stories.

However, when Nathan quotes Mathilda Steinberg of Recife Brazil in a recipe for “Brazilian-Belarusian Grouper with Wine, Cilantro and Oregano” who says of her recipes, “I hope that the next generation will feel the desire to pass on these foods. That’s the way the Jewish people have always continued” she could also be speaking for herself. Nathan’s own mother passed away at 103, this past February, after having had a chance to see that, in this cookbook, Nathan was carrying on traditions of her mother’s mother.

For Ms. Nathan, food and culture are inseparable. As she told the Washington Post in a recent interview, after her first time living in Israel for a few years with her family in the early 70’s, “I saw not a clash but a coming together of civilizations. You know, for me, Jewish food was my mother’s matzoh ball soup. Then I went there and I saw stuffed vegetables and all kinds of salads that were different, and this was in the early ’70s…. I realized then that food was culture, and it was not restaurant culture. It was ethnic culture.”

The Wisdom Daily caught up with her briefly by phone as she awaited a plane to Providence RI, where she grew up, her own mother who passed away this past February resided, and her brother, who she was going to visit, still lives.

WD: Why is a book about Jewish foods from around the globe and the cross-pollination of Jewish recipes relevant at this moment?

JN: Well, first of all, because the fabric of America is being questioned right now. We are a nation of immigrants and immigrants have enriched our country in every single way. And I also think all the ingredients for so many dishes…pomegranate paste, date jam, kiwis, they all came from different places and we have them in the US. People have to go to those places and come from those places for food to be here. And then, who helps in kitchen? Immigrants.

WD: Can you talk a bit about the history of seder foods?

JN: The seder came out of a spring festival in the ancient world, it was not the Passover seder as we know it till after second expulsion(from Israel). King Solomon would have had a springtime feast, most likely a roasted lamb and he would have had unleavened bread and maror, the greens that come from the earth. Maror in Arabic means greens.

Horseradish came when Jews went north to Alsace- Lorraine and Germany. France was the center of horseradish production in the medieval era, 10-11th century.

WD: How do you decide what is on your own seder menu?

JN: Chicken soup matzo balls, gefilte fish. Some traditional dishes, some new – artichokes from Italy, hardboiled eggs with spinach from Greece. I used to have salt water and egg, then egg and spinach, which we like so much we replaced my in-laws tradition of starting the meal with an egg. Five kinds of haroset. I always integrate to the seder salad or vegetables, and I always want to find a good chicken dish. Flourless chocolate torte. My father’s recipes for chremsel and prunes. I have an amalgamation of different recipes, and it depends on who the guests are and who wants to bring something.

WD: How does your approach to food fit into Pesach? Incorporating journeys of Jews?

JN: You learn traditions from everyone you speak to. When you interview them or go to their home, you learn things. I don’t like all these modern recipes that are just pretty. I like a connection, a connection to the past.

WD: How do your recipes connect you to the past?

JN: When my mother looked at the book, she was 103, [she told me] “I am so excited, you started the book with my mother’s recipe.’ She thought the recipe for “Huevos Haminados con Spinaci, Long-Cooked Hard Boiled Eggs with Spinach” was like a recipe her mother made with eggs and chopped onions.

Nathan added that her own mother had always “felt bad about not having a good relationship with her own mother, and was moved that in her daughter’s book, she was carrying on her mother’s traditions.” Nathan added, “She died the next day.”

WD: Advice for those cooking for seder?

JN: Make a long list. Make as many lists as you can. Lots and lots of lists. Make a time line and allow a lot of time for shopping.

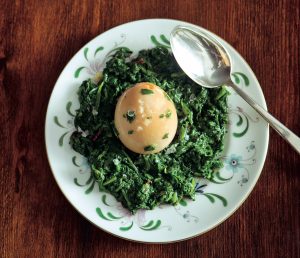

Huevos Haminados con Spinaci,

Long-Cooked Hard-Boiled Eggs with Spinach

yield: 12 to 16 servings

12 to 16 large eggs, preferably fresh from a farmers’ market

4 tablespoons olive oil

1 large (about 225 grams) red onion, peeled and coarsely chopped (1 ½ cups)

1 tablespoon sea salt

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

1½ pounds (680 grams) spinach, fresh or frozen (thawed and drained if frozen)

One of the most ancient symbols of birth, rebirth, and mourning is the incredible egg. Observant Jews eat them for breakfast or lunch on the Sabbath, cooked overnight in their Sabbath stew or boiled in water laced with onions or coffee for flavor and a dark color.

The symbol of the round, smooth egg for rebirth is especially universal in the spring, the time of an abundance of eggs because there is more daylight, and more for hens to eat. “Factory” hens will still lay eggs through the winter because they are kept under artificial lighting and tricked into thinking it is spring and summer because there is more light.

Eggs, a product of the fowl domesticated by the Chinese in about 1400 b.c.e. and then shipped west, are significant in cultures the world over–from ancient Persia to modern India, from small Italian villages to mainstream America. In Jewish communities, the egg is also a symbol of mourning, both personally and communally. When someone in an observant Jewish family dies, the first thing that is traditionally eaten after the funeral is a hard-boiled egg.

As a community, Jews put a roasted egg on the Seder plate as a symbol of life and of mourning for the destruction of the First and Second Temples of Jerusalem. And many Jews have the custom of starting the Passover Seder with eggs, either cooked in salt water or even cooked overnight in sand, a custom still followed today in North Africa.

This recipe for long-cooked eggs with spinach came from the island of Corfu, Greece, to Ancona, Italy, a seaport on the Adriatic coast. I tasted it in Rome, loved it, and it is now a keeper at our Passover Seder. Daisy Dente Modigliani, who shared this recipe with me, hard-boils sixty eggs to serve as the first course of her Passover Seder for both the first and second nights.

This recipe has replaced our simpler family Passover tradition from Poland of serving hard-boiled eggs in salt water, a custom I learned from my mother-in-law when I married my husband many years ago.

- Put the eggs in a cooking pot and add water to cover by about 2 inches. Then add the olive oil, onions, salt, and pepper. Bring to a boil over medium-high heat, then lower heat and simmer for 30 minutes. Cool and remove the eggs with a slotted spoon. Tap the eggs gently against the counter and peel under cold running water, keeping them as whole as possible.

- Return the peeled eggs to the pot with the seasoned water and simmer very slowly uncovered for at least 2 hours, or until the water is almost evaporated and the onions almost dissolved. The eggs will become dark and creamy as the cooking water evaporates and they absorb all the flavoring.

- Remove the eggs carefully to a bowl, rubbing into the cooking liquid any of the cream that forms on the outside. Heat the remaining cooking liquid over medium heat, bring to a simmer, and add the spinach. Cook the spin- ach until most of the liquid is reduced, stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon, about 30 minutes, or until the spinach is creamy and well cooked. Serve a dollop of spinach with a hard-boiled egg on top as the first part of the Seder meal or as a first course of any meal

Note To see if the eggs are really boiled, remove one egg from the water and spin it on a flat cutting board. If it twirls in one place, it is hard-boiled. If it wobbles all over the board, it is not cooked yet and the weight isn’t distributed evenly. The easiest way of peeling a hot hard-boiled egg is to put it under cold water between your hands and rub it quickly until it cracks, then peel under the running water.

To prepare the symbolic egg for the Passover Seder plate, boil the egg in its shell, dry it, and then light a match underneath to char it.

Beth Kissileff is the co-editor of the anthology Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy, author of the novel Questioning Return and the editor of the anthology Reading Genesis. Her writing has appeared in the Atlantic, Michigan Quarterly Review, New York Times, Tablet, the Forward, 929English and Haaretz, among others. Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.