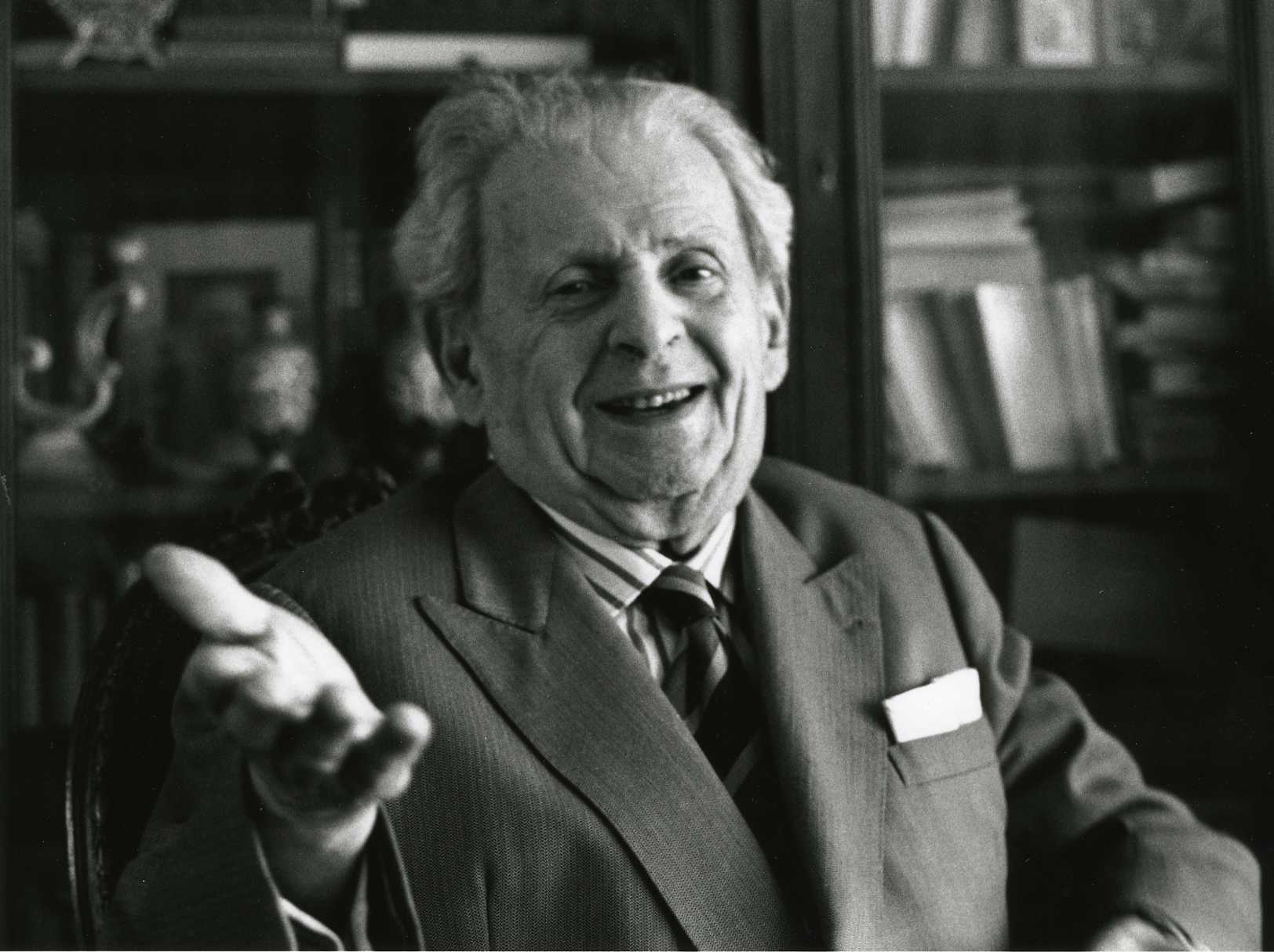

Over the centuries many philosophers have taken up the nature of the self and its knowledge. Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995), in contrast, was concerned with the Other and her demands. Levinas, a Lithuanian born Jew and Holocaust survivor who rose to be one of the most important philosophers of post-WW2 France, spent his career analyzing our relationship to the humanity of the Other, which for Levinas was the most important issue in human existence.

Levinas was viewed as one of the most important European thinkers of the 20th century. Championed by Jaques Derrida and many others, Levinas had a rapidly growing audience in his last years that has only expanded further since his death. His influence has spread beyond philosophy to literary theory, film studies, psychology and politics.

Whereas for many philosophers the question of the ethical follows that of the ontological (“what is real”) for Levinas, philosophy begins in the ethical. All questions of reality and non-reality, truth and lies, action and inaction, follow upon the face to face meeting with an Other who I am responsible for, whom I have the power to kill or not to kill, whose subjectivity forever escapes my grasp, challenging my hegemony and my egotism.

For Levinas, the face of the Other both fundamentally structures my human universe and exists as a constant challenge, calling my being into question and, in so doing, birthing me as a moral human, or to be more blunt, as a human being at all.

In our time, we’ve seen an ascendancy of “me first” politics, whether it is the “me” of the ethnostate, of my religion, my race, my identity, or the “me” of the capitalist. Ethno-nationalism, violent jihadism, white supremacy, identity politics, and neoliberal economics all have in common an argument for why I should attend to my own interests first, whether those interests are interpreted as being those of myself, my family, my tribe, or my country.

For Levinas, humanity dwells in recognizing our total reliance and interdependence with others and the acute responsibility that lies on us because of the vulnerability of the other who comes before us. The fundamental ethical command is “do not kill,” by which he means practice no violence toward the other; do nothing which negates their humanity or your responsibility towards their call.

It is hard to argue that a viable human future can be based on anything other than Levinas’ vision and its reflection in societal structures which enshrine the protection of the other in culture and law. The opposite vision, so well embodied by Trump, but encouraging simalucra throughout the world like bacterial echoes, is one of political and cultural victory through radical selfishness and violent posturing. The other is never met with help but only demands. This is not only antithetical to the human future, it is emboldening all those who embrace the raw egotism that Levinas called, no doubt with a hint of irony, “atheism.”

Beyond this diagnosis, Levinas offers us a practical insight with regards to discourse in the Trump-blasted wilderness we currently inhabit. The disappearance, in the places of power, of the normal laws of conversation, where one tries to speak truthfully, tries to be as truthful as possible, or at least tries to appear to be telling the truth in the eyes of a reasonable observer, is chilling. So is the fevered polarization in public discourse with its attendant disappearance of listening and its weakening of collective action for the common good.

In Levinas’ way of thinking, there is no truth outside of human discourse. Discourse- the face to face encounter where we present the world to each other- is the fundamental organizational principle which creates the field in which the concepts of knowledge and truth exist and have meaning. Without discourse, we as individuals would have no concept of truth and would not seek it or possess it.

On the basis of this claim, Levinas states that it is a mistake to think that truth precedes justice. We may think that if people had better information they would be more just, but Levinas says this is not so. In fact, argues Levinas in his first masterwork “Totality and Infinity,” justice precedes truth. Truth is not an abstraction acting under its own power; truth only exists in the mind that receives it, and it exists on the basis of a human world of sincere, lawful (i.e. just) discourse.

Truth is not something possessed by an imaginary solipsist, a pristine mind confronted with the mystery of the universe- because such a person is a chimera. Truth and falsehood arise only socially, in human community, even if truth is found in a mind that has retreated to ponder what it heard among others.

The value of truth depends on the justice of speakers- only in a world of sincere discourse can the quest for human truth even arise. As it turns out, the entire social fabric of humankind relies on people following the laws of conversation. This is a reason that the blithe disregard for truth currently echoing in the halls of power is so concerning.

It also points to where we should be focusing our attention- not on yelling truth at each other but on asking how to restore justice to the discourse. Why are people not speaking sincerely? Why are people not listening with a regard for truth? What are the mechanisms that condition them to use the rhetoric of truthseekers while being so devoid of any concern for what is true? How do we inspire conversations where both sides are honestly searching for the truth?

C.S Lewis pointed out that in his day almost no one was concerned with what was true. Instead of truth they were concerned with what was “modern,” or “traditional,” “progressive” or “conservative,” or what have you, and throwing one of those sobriquets at something or someone was enough to twist the conversation and cloud the issues. It seems that is more the case today than ever, and that all of us- not only Sean Spicer- have to take a renewed interest in what is true.

That is an effort which can not only take place in our thoughts, but must also take place in our conversations, and in our attempts to build them on the justice of both speakers and listeners. What conditions need to be in place for sincere discourse to take place? Unless we ask that question, every time we engage with someone with whom we disagree, we are unlikely to get anywhere.

For Levinas, the conditions for just discourse are honesty, fairness and desire for the truth. If one of those is absent, how can the truth be found between the speakers? If one is absent, unless we try to restore it, we are wasting our time. This leads us to ask, if one is missing, what needs to be there for it to be restored? Assuming we are being honest, fair, and open to truth, how do we help our interlocutor regain one of those attitudes? What do they need to feel comfortable enough to be honest, to feel generous enough to be fair, to feel companionable enough to search for truth together?

“To approach the Other in conversation is to welcome his expression”, wrote Levinas. “But this also means: to be taught. The relation with the Other, or Conversation, is a non-allergic relation, an ethical relation; but inasmuch as it is welcomed this conversation is a teaching.”

Matthew Gindin is a journalist, educator and meditation instructor located in Vancouver, BC. He is the Pacific Correspondent for the Canadian Jewish News, writes regularly for the Forward and the Jewish Independent and has been published in Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Religion Dispatches, Kveller, Situate Magazine, and elsewhere. He writes on Medium from time to time.