How do you live well? And when the times comes, how do you die well? There is no single or simple answer to either of those questions, but there is real wisdom that can help us all to answer those questions better.

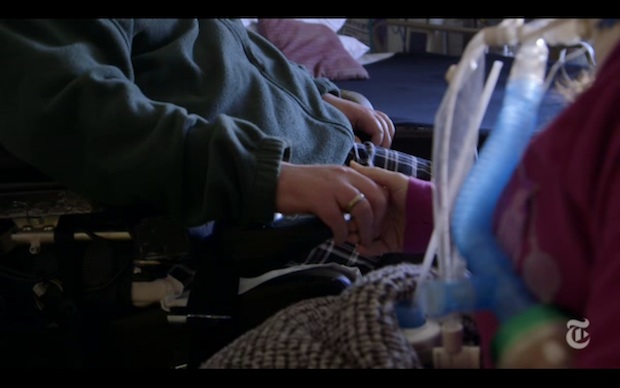

This story in the New York Times and its accompanying video (see below) describe, with exquisite poignancy, different patients’ experiences in a long-term care hospital, i.e., a place where people may reside for years, but very few of whom will ever recover from the terminal diagnoses which brought them there. These patients are quite sick, many dying, and they have so much to teach us about life.

When people find sufficient love and meaning in their lives, the courage part pretty much takes care of itself.

I pay especially close attention to these stories not only because my daughter spent last summer interning in a similar facility, but because through firsthand stories, we can be inspired about choosing life and finding meaning, even under pretty daunting circumstances.

Frankly, although the Times story concludes with a reflection on a patient having the courage to die, I’m not sure that the end-of-life decision is about courage. Are you? Is courage even the proper state of mind through which to analyze life-and-death decisions?

We use so much military language when it comes to illness, death and dying. We “battle” disease, “conquer” the illness, patients “pull through” or “lose the fight.” And yes, we celebrate the courage of sick people – sometimes their courage to live and sometimes their courage to die. While the animating logic behind these word choices makes real sense to me, I wonder if it always serves patients, their families or the rest of us as well as we think.

If accepting the end is called “giving up,” aren’t we implicitly pushing the patient to go on, whether that makes sense or not? Conversely, if we praise a patient’s “courage to die,” are we incentivizing a premature death?

Perhaps, instead of asking what’s the courageous thing to do, especially in moments of life-or-death decision making, we might consider this question: What is the loving thing to do? Perhaps, instead of asking what’s the “bravest” decision a patient can make, we invite conversations about what is the most meaningful one for them.

And don’t worry about missing out on the courage thing, if that’s important to you. My experience has been that when people find sufficient love and meaning in their lives, the courage part pretty much takes care of itself, whether it has to do with living, dying, or everything in between.

Listed for many years in Newsweek as one of America’s “50 Most Influential Rabbis” and recognized as one of our nation’s leading “Preachers and Teachers,” by Beliefnet.com, Rabbi Brad Hirschfield serves as the President of Clal–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a training institute, think tank, and resource center nurturing religious and intellectual pluralism within the Jewish community, and the wider world, preparing people to meet the biggest challenges we face in our increasingly polarized world.

An ordained Orthodox rabbi who studied for his PhD and taught at The Jewish Theological Seminary, he has also taught the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs an ongoing seminar, and American Jewish University. Rabbi Brad regularly teaches and consults for the US Army and United States Department of Defense, religious organizations — Jewish and Christian — including United Seminary (Methodist), Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (Modern Orthodox) Luther Seminary (Lutheran), and The Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative) — civic organizations including No Labels, Odyssey Impact, and The Aspen Institute, numerous Jewish Federations, and a variety of communal and family foundations.

Hirschfield is the author and editor of numerous books, including You Don’t Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism, writes a column for Religion News Service, and appears regularly on TV and radio in outlets ranging from The Washington Post to Fox News Channel. He is also the founder of the Stand and See Fellowship, which brings hundreds of Christian religious leaders to Israel, preparing them to address the increasing polarization around Middle East issues — and really all currently polarizing issues at home and abroad — with six words, “It’s more complicated than we know.”