Explaining where I was and how I felt this morning is complicated. I’ll begin with the basics. About four years ago I started making calls to a wounded warrior organization called the Wounded Warriors Family Adventures, which takes place in Breckenridge, Colorado every April. To my knowledge they’re one of the only veterans groups that work with severely injured soldiers and their entire families. In fact, just to qualify for this program you must be married, and both husband and wife need to be living together underneath one roof.

My many calls and emails to the program’s facilitators went unanswered for nearly a year as I tried to make the case that I had a set of skills that might be helpful to these soldiers and their families. But having no psychology background and no military experience whatsoever wasn’t exactly making anyone in that organization take notice. I understood that. Why would anyone want a middle-aged songwriter from Santa Monica to mess with the minds of these physically and psychologically scarred soldiers and their families?

Eventually I did get to speak with a man named Bob Miller, a retired Colonel from the United States Army. I was able to convince him that through my music and a creativity development program I’d been working on, I might be able to add to his organization’s main objectives, which I understood as opening up lines of communication between the family members. It was a communication that had largely shut down; in many cases it had been deteriorating for several years.

I told Bob about the work I’d been doing with different universities and corporations and how I believed I might be of help. The thing that seemed most compelling for him was the fact that my dad had been a Marine, and that even as a rock musician –with all its presumed anti-military associations, I had always been predisposed to admiring armed service personnel. Bob asked me to come to Breckenridge soon after that initial phone call, and my first workshop was successful enough that I was asked to come back every year. “If you don’t want to join us next year,” one of the facilitators said at the time, “You’d better change your phone number and your address, because we will find you.”

Each time I come to this mountain it gets more and more intense. Because there’s no effective way to prepare for this kind of thing it always feels new, and as a result, I go totally sleepless the night before. ‘What if I don’t get through to them? What if they think I’m a fraud? What if I have nothing of value to say…?’ To make matters even more complicated, the facilitators wanted the soldier’s young children to be involved in the sessions — as opposed to last year, when they were tucked away in another room, drawing pictures and making animals out of Playdough.

Through no fault of their own, kids tend to take over, and they wind up creating the baseline for everything you say and do. Therefore, it must all be understandable (on some level at least) if you want to hold the children’s attention and not have them become disruptive. Because while adults have all been children, children have never been adults — though I will say that this group of seven and eight-year olds were as close to adults as I’ve ever seen, given their proximity to such enormous psychological and physical trauma.

I began the session by telling the group how proud and honored I was to be there with them, and then by making up some songs about a couple of the little girls that were sitting with their families. After that, I told the group a story about my dad. In 1983, when he was near the end of his four-year battle with stage IV lymphoma, I had written him a song called, This Father’s Day that expressed how much I loved him. I turned on my iphone and played the recording of the song I made those many years ago. Very audible at the very end of the recording, is me breaking down in tears.

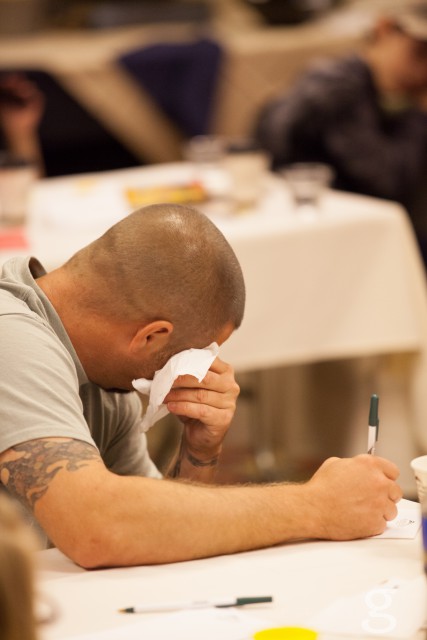

Playing the song was an invitation of sorts, a silent permission for the group to open up to the idea of writing letters to one another. “Soldiers,” I said, “I want you each to take five minutes to write a letter to your wife and kids, to tell them how much you love them, and how proud you are of them. Wives and kids, I want you to do the same for your husbands and dads.” The constraint of the time limits made it easier to write, made it somehow less daunting to pour out emotions that had long remained locked away. The room grew silent as they wrote.

If expressions of love had been hard to find in the families’ households over the last several years because of PTSD and anger issues, it was present now, and when I asked the soldiers and their families to read their letters aloud the men and women rose, one after the other, saying things that were unimaginably touching in their unadorned beauty. For me, watching these people share their emotions through tears and pain was among the most profoundly religious moments of my life. These were people who hadn’t until this morning, found the appropriate context to pour out, not just their hurt and anger–which they’d surely done countless times–but to declare for all to hear, their words of love for their spouses, for their children, and for God.

I’m fortunate to know several artists and poets, some of them great ones, but I have rarely heard the kind eloquence I heard from these families. When you see men and women, children too, bravely overcoming the native human reluctance to reveal vulnerability, it changes you. When you see these wounded soldiers telling their children how proud they are of them, hugging them, kissing them for perhaps the first time in years; you become wiser. In that instant, the thing we all instinctively know –that fame, and wealth and power are fleeting –suddenly becomes as real a fact as a tree or a stone.

It is then you realize that you are witnessing something of greatness. And when you see real greatness, not something marketed or foisted upon you by a thin and desperate culture, you become silent and still. Perhaps it’s that stillness that we most crave, that most resonates with us. All my life, as a musician, as a poet, as a religionist, I’ve been searching for those moments. Moments when the skin of things is pushed aside and the soul, the essence, is laid bare.

Later, when I spoke with a few of the soldiers they told me that their time on the field of battle hadn’t prepared them for the bravery it took to say the things that were said in that room this morning. To me though, the men are all uniformly brave, both in combat and in the world of emotions. Having been so close to death and to unspeakable loss, they have developed an acute sense for what is of greater value and what is of lesser value.

The soldiers uniformly rejected the appellation, “heroes,” which some people on the staff had called them. “It’s the ones who didn’t make it back that are heroes,” is what they told me. But I begged to differ with them. A hero is one who gives his or her life in service to a cause beyond him or herself, and these men have truly done that. Sometimes that service takes the form of violent conflict, other times it takes the form of battling with one’s own fears, so that others may grow and prosper.

As I was about to leave for the airport Bob Miller took me aside and thanked me for having come up to the mountain. But even as he said it, I knew that it was me who was the most grateful, by far.

See some images from my visit below (Photos by Garrett Hacking, photography G):

Peter Himmelman is a Grammy and Emmy nominated rock and roll musician, visual artist, author, film composer, and speaker. Peter’s new book, Let Me Out (Unlock your creative mind and bring your ideas to life) is available here.