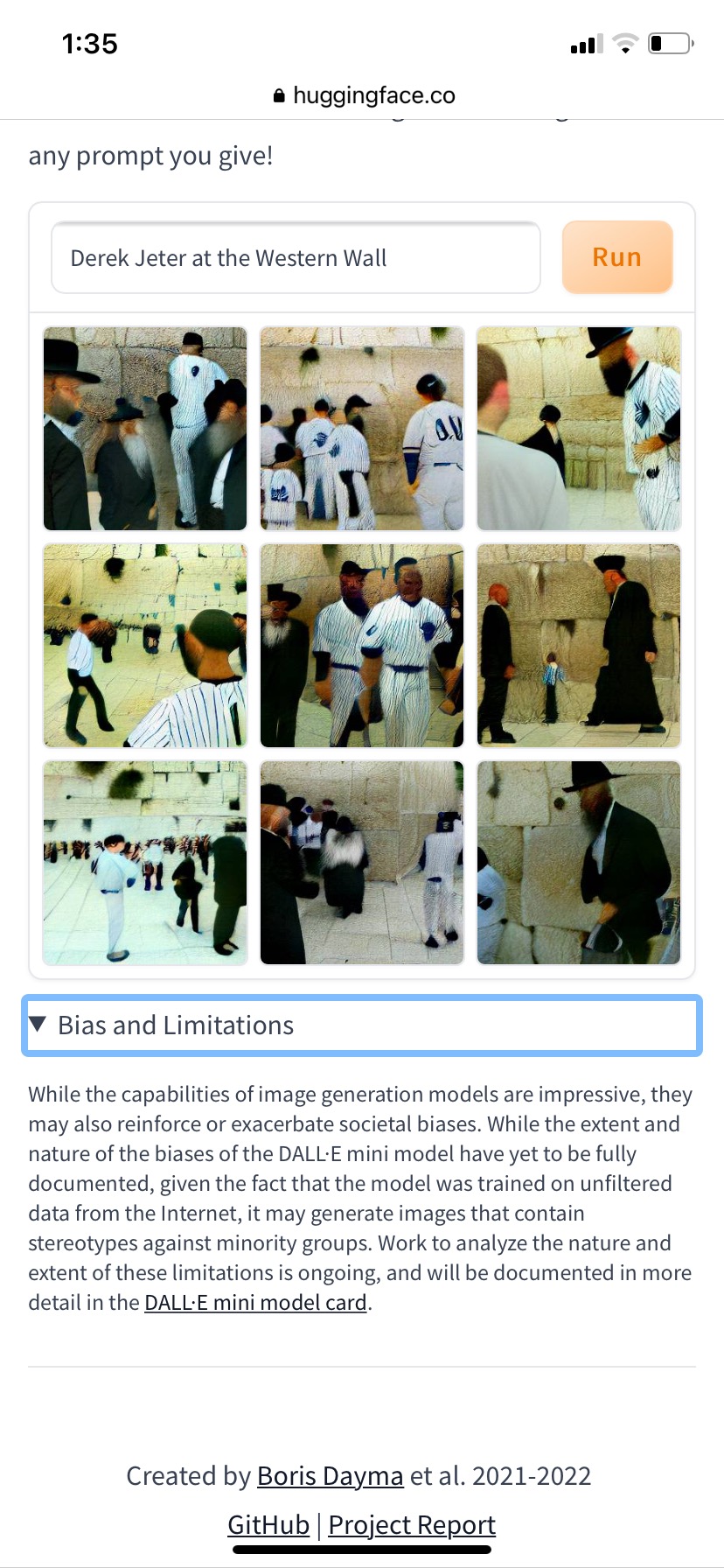

We all know that a picture is worth a thousand words. But how about transforming the words into pictures? That’s the idea behind a new open-source AI called Dall-E Mini, where you type in a text prompt, and it creates an image that’s amazingly representative of the text prompt. If you’ve ever wanted to see Derek Jeter at the Western Wall, a triceratops running in the 1964 Olympics, or Sonic the Hedgehog as a guest star on “Friends,” this is the site to visit.

Aside from the fascinating way in which it works, I’ve been struck by the dynamic between the chosen words and the AI-generated image. It’s one thing to imagine unusual ideas in words, but the visual punch brings it to a whole new level. And while the words are intentionally chosen, once the images are created, you can’t unsee them – whether you want to or not.

This week’s Torah portion, Sh’lach l’khah, emphasized the power of visual reminders over a long string of words. The very end of the portion includes a section that was later included as part of the Shema liturgy, where we are commanded to make fringes and attach a blue cord (tzitzit). Rather than trying to remember the language of all the various mitzvot, which were written down, the tzitzit was designed to be visual and immediate. We are to “look at it and recall all the commandments of ??”??” and observe them, so that [we] do not follow [our] heart and eyes in [our] lustful urge.” (15:39). And while we tie the tzitzit on purpose, once we see them, we can’t ignore it.

Along those lines, the Rabbis note that “You find that three organs fashioned by the Holy One, blessed be God, are under our control, and three are not under our control. We control the functioning of our hands, our mouth, and our feet…The organs not under our control are our eyes, our ears, and our nose.” (Midrash Tachuma Toledot 12) As they remark, if we want to, we can use our hands to perform mitzvot (such as putting on tzitzit), or we can use them to shed blood. We can use our mouths to speak kindly to others, or we can lie. We can use our feet to go to visit the sick, or we can use them to go steal. However, we also have experienced seeing things we wish we hadn’t heard things we wish we could forget, and smells would have rather avoided.

Similar to the Dall-E prompts, we can choose our words, but once ideas are out in the world, the things we see and hear are outside of our control. We can’t turn a blind eye or a deaf ear, even if we wanted to. But that lack of control actually has great power, because it also means we can’t ignore injustice or pain or suffering. It’s then upon us to act. As Menahot 43b says, “Seeing leads to remembering, and remembering leads to doing.”

Language is incredibly powerful, but our visual cortex has a much deeper and longer evolutionary history. So much of Judaism is verbal, complex and nuanced, and hard to conceptualize succinctly. But seeing a blue thread is an immediate visual, capturing at least a small part of the essence of the 613 mitzvot. And as both Dall-E and tzizit show us, it’s one thing to talk about an idea; it’s entirely different to see it.

And while we can’t necessarily transform our words into images perfectly, once we imagine things – such as a world of peace and justice – we can then use our mouths, our feet, and our hands to turn it into a reality.

Rabbi Geoffrey A. Mitelman is the Founding Director of Sinai and Synapses, an organization that bridges the scientific and religious worlds and is being incubated at Clal – The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership. He was ordained by the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion and served as Assistant and then Associate Rabbi of Temple Beth El of Northern Westchester. In addition to My Jewish Learning, he’s written for The Huffington Post, Science and Religion Today, and WordPress.com. He lives in Westchester with his wife, Heather Stoltz, a fiber artist, and their daughter and son.