The Torah has been translated into nearly every written language. It has passed from Hebrew into Greek, from Greek into Latin, and from Latin into the English with which these words are written. The Torah, as written and spoken, might most laconically be characterized as the story of the Jewish people as told by the Jewish people. It is a story, but it is also a conversation; a conversation that can also be understood as a sacred dialectic through which the Spirit of history plays out.

But the Torah can also be characterized and defined in other ways. Abbreviated even further, perhaps even to its essence, the first word of each of the five Books of Moses form the following acrostic, translated into English:

“In the beginning… Names!

And He called in the desert… words.”

Does this not concisely describe the five Books of Moses in both form and content? These five simple words uncoil the whole text of the Pentateuch, the part reflecting the whole, from Genesis through Deuteronomy, from Bereshit through Devarim. “Names” and “words” affirm the significance of language and give form to a holiness that is abstract, giving it life within a tradition that eschews the concreteness of images and idols.

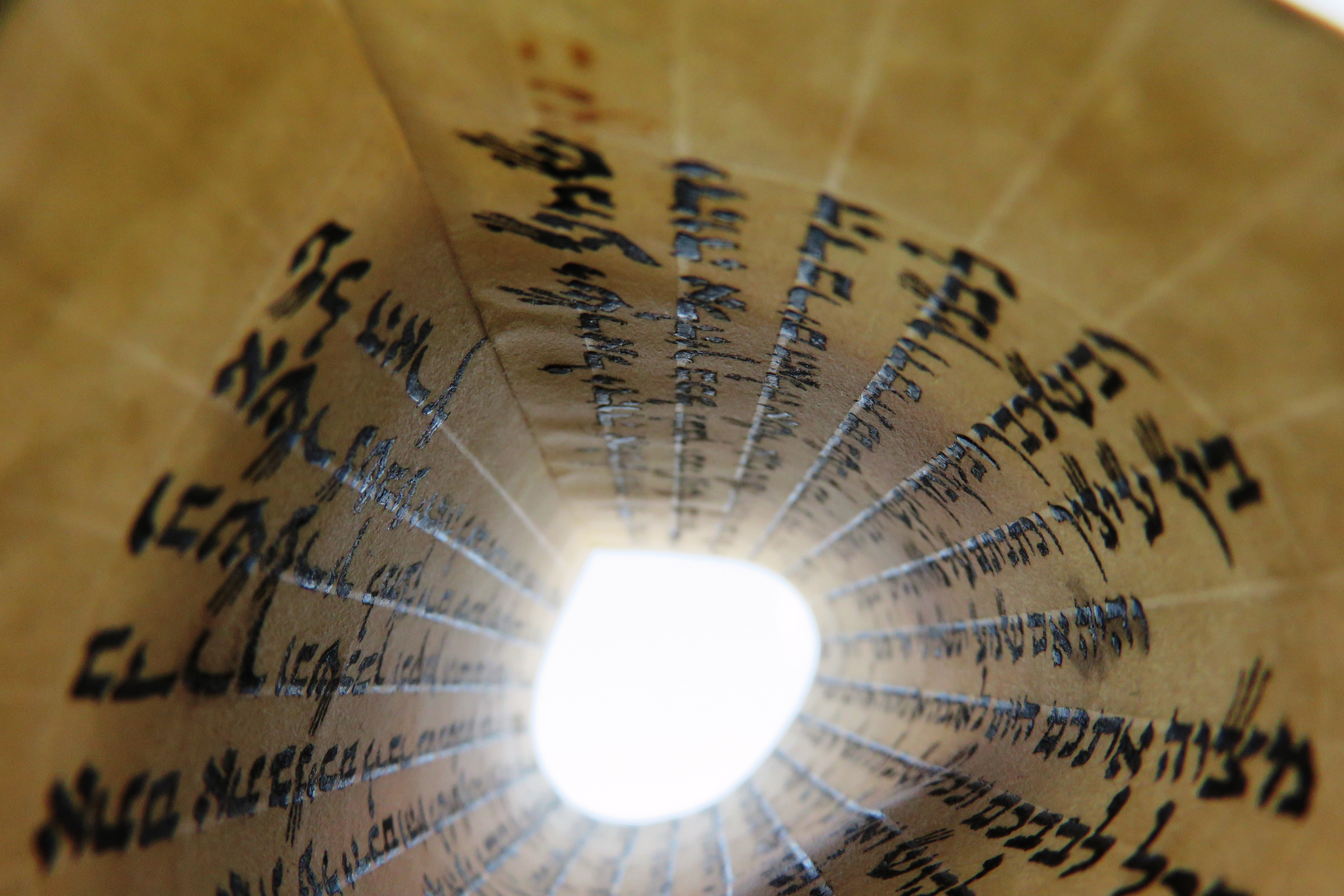

In maximalist or universalist terms, beyond the Pentateuch, beyond the Writings and the Prophets, beyond the Oral Law and centuries of Rabbinic commentary, the Torah might be said to be a conversation that reflects all conversations in all times and all places. Throughout the millennia, these conversations have found myriad expressions in the texts and beliefs of other religions beyond Judaism and are a fundamental cultural element of Western civilization. This perpetual conversation, this “eternal light,” including all related religious and secular traditions, transcends the historical context of the Torah, like a Borgesian mirror that reflects everything all at once, reflecting the light of what was, what is, and what will be. From this vantage point, every conversation is an aspect of Being and becoming. Every conversation is an interpretation that depends on the period, place, and people engaging in the interpretation. Every conversation is a spark that is part of a greater light. In this sense, the Torah is the aggregation of all conversations that constitute the Spirit of History.

This cultural progress, this process of becoming across many traditions, is an ongoing hermeneutical project. There are many ways to encounter the text. The hermeneutical tradition within Judaism is usually divided into four complementary categories: Peshat examines what is on the “surface,” or the most literal interpretation of the text. Remez gives “hints” to the allegorical meaning beyond the literal meaning. Derash is comparative and dialectic, while Sod reveals the esoteric, mystical, and concealed aspects of the Torah.

But for all the ways in which we might understand the text, there remains a more fundamental matter of exegesis and translation, which raises questions about the nature of language itself.

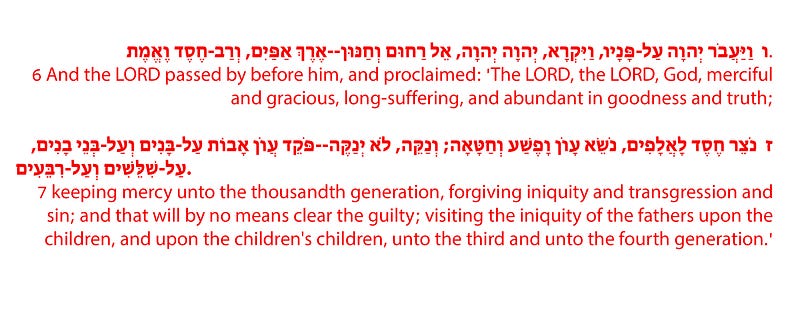

There is a tradition that Hebrew was the language with which G!d created the world. At least as far back as the Sefer Yetzirah, and probably long before that, the relationship between language and creation has been understood by commentators on the Torah, and on Genesis in particular, as being dependent on language. When G!d created the creatures and things that would come to populate the world, G!d did so through speech acts, Names, and words. What was said was what was done. What a thing was called gave form to what it was. It was this performative function of language that imbued each word, each character, with its natural or inherent meaning.

This notion that language has a natural or inherent meaning, even a divine significance, is at odds with the modern understanding of how language works. This shift emerged most distinctly in the early 20th century through the work of Ferdinand de Saussure and the Structuralist tradition he laid the foundation for. Structuralism has had an immense influence on how meaning is understood to be constructed and exchanged.

Saussure had at least two important insights with regard to how language works. The first is that language is made up of signs and that these signs have two parts: a signifier and a signified. The word “book” is a signifier that is perceived to signify the concept of a book. However, there is nothing inherent or naturally meaningful about the characters B-O-O-K; there is no essential “bookness” in the characters B-O-O-K. Therefore, the relationship between the signifier and signified is arbitrary.

But if the relationship between the concept and word, between the signified and the signifier, is arbitrary and not inherent, as is claimed in the aforementioned Jewish tradition of biblical exegesis, then how does the sign obtain a stable meaning?

The second insight is that rather than language possessing a positive, inherent, or essential meaning, Saussure asserts that meaning is constructed through difference and contrast. I understand a “book” to be a book only because I understand that it is not a tree or a house. I understand it as a sign within a system of signs, and that contrast and difference with other signs is what gives a sign its meaning.

So we have two claims: One is the claim that there is a deep structure to the text, reflected in the natural universe itself, based on inherent, essential, and positive features of the text. The other is that the structure of the text is arbitrary and predicated on differences within a system of signs. This brings us to our present project – the translation of the Torah into light.

A translation is always less and always more than what is being translated. It makes the text accessible to an audience who would not otherwise be able to understand its meaning. It also denudes the text of the meaning it may have had in its “original” context.

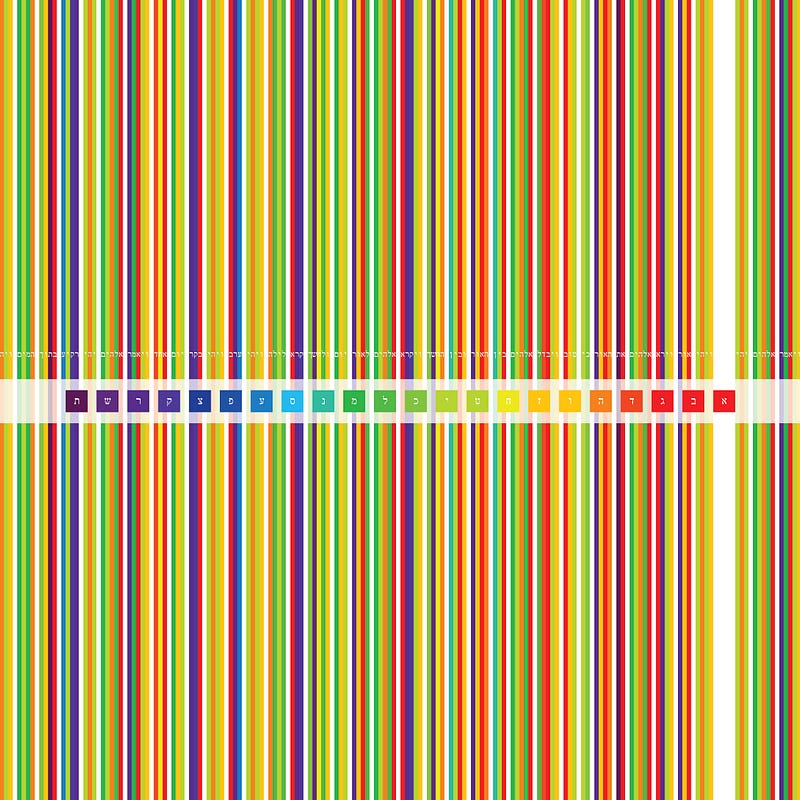

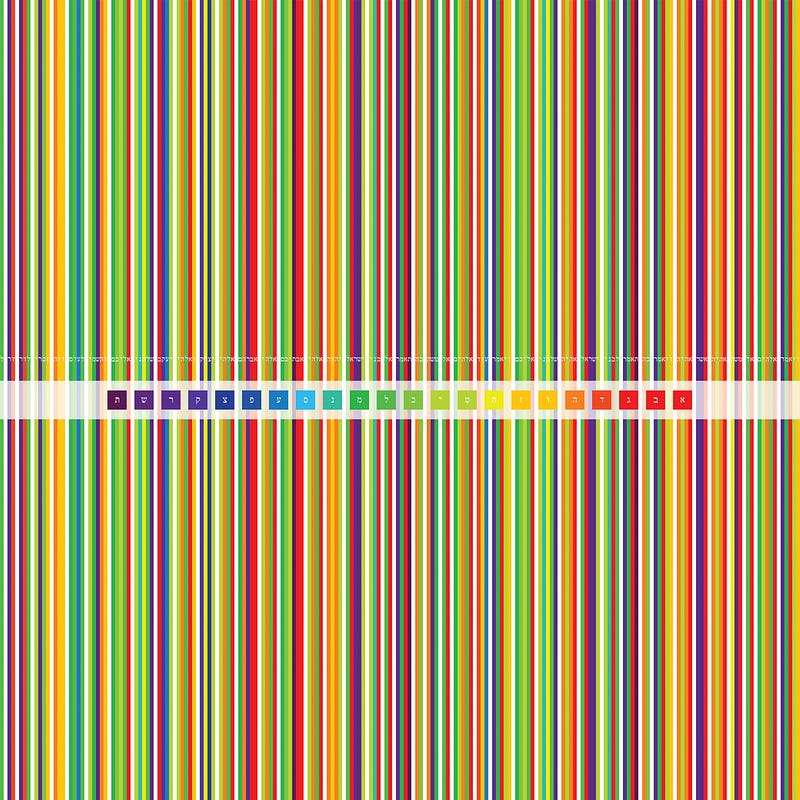

The methodology employed here is based on interpretations of the Sefer Yetzirah and other commentaries, as well as initial experiments into the translation of the Torah into sound and music. There is an ancient tradition that each character in the Hebrew alphabet also has a meaningful, numerical equivalent. This tradition is called Gematria (interestingly, both “gematria” and “alphabet” are translated from Greek words).

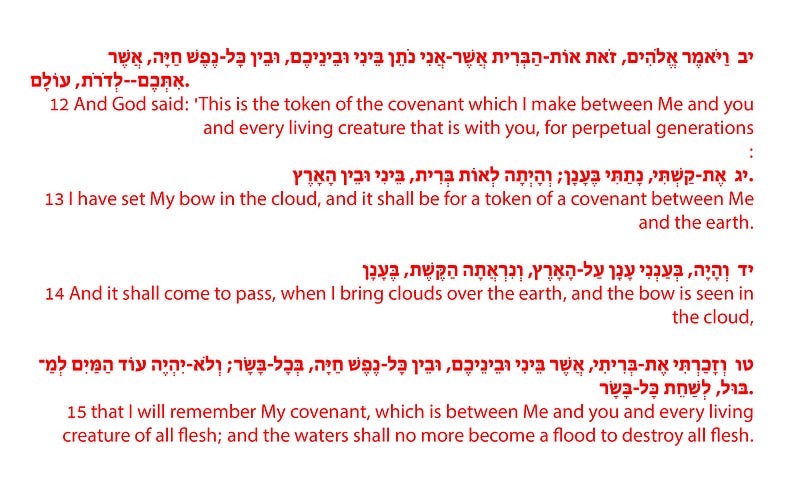

It stands to reason that if a letter can be translated into a number, then that number can be given a chromatic value as well. By mapping each character’s position in the Hebrew alphabet to correspond with a color on the visible spectrum, we can translate these chromatic values from the text. We can translate the text into light.

Some viewers will look at these patterns of color and see only noise. Some may even encounter an aesthetic experience in the arbitrariness of that noise. Others may see meaning and significance and perhaps something of a hint at a deep structure that dwells within the text… but I leave it to the viewer to decide.

Ian Gonsher is Assistant Professor of Practice in the School of Engineering and Department of Computer Science at Brown University. His teaching and research interests examine creative process as applied to interdisciplinary design practices. Recent work includes Ian’s teaching and research within the Brown Humanity Centered Robotics Initiative, and explores the ways technology might enhance our humanity, rather than rob it from us. He is also working on a translation of the Torah into light. More information about his work can be found at his website.