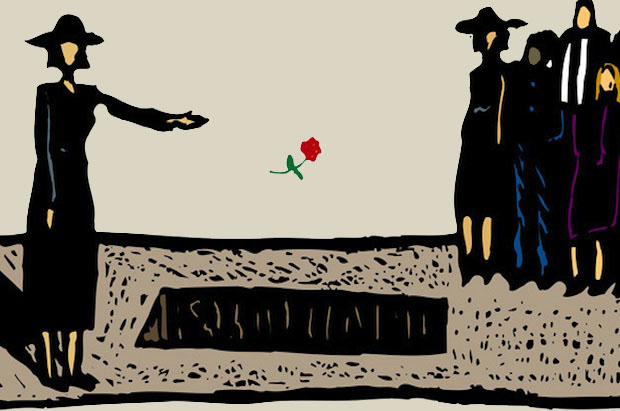

How we deal with death tells us a great deal about how we think about life. No surprise there, right? More surprising: Almost all the ways that we deal with death are changing, leading to what some call the death of funerals.

It’s not that funerals are going away anytime soon. But they’re certainly being redefined in profound ways. Consider the rapidly rising popularity of cremation over burial. Cremation, which once accounted for a mere 3.6% of dispositions in 1960, now accounts for almost half! In 2013, more than 45% of Americans and their families chose cremation.

Traditions and rituals are living things which change over time.

Given how seriously people take death rituals and practices, this shift has the potential to divide family members at a moment when they need to come together most. Not to mention that, typically, cultures change quite slowly when it come to entrenched practices.

So what’s going on? Probably a bunch of things, from increasing mobility to the decreasing appeal of traditionalism, from tightening budgets to expanding personalization.

Americans are more mobile than ever, hence our declining connection to the “permanence” of in-ground burial (or to family plots and cemeteries where generations of our ancestors lie). Maybe that’s not a good thing, but it’s real. It doesn’t mean people don’t care deeply about how to honor departed loved ones; in plenty of cases, they care so much that they want to honor their beloved in a way that helps them stay more connected, even in a time of great mobility.

Add the legitimate factors of job insecurity and income stagnation, and it further incentivizes choosing the (more economical) route of cremation over burials. Furthermore, cremation has far less tradition and religious structure (ceremony) around it, at least in our country, so we can understand why a generation of Americans who feel free to choose their own rituals and religious authorities would be open to cremation. In fact, people are especially comfortable organizing funerals without the direct involvement of clergy when a cremation is involved.

To be clear, my own tradition sees burial as pretty much the only option, and I admit that my own feelings about cremation are influenced (almost?) as much by Holocaust memory as by tradition. Of course, traditions, rituals and memories are living things which change over time. In fact, the very Jewish traditions which so privilege in-ground burial once included the steps of digging up the beloved’s bones and saving them in boxes at home – not unlike the practice of keeping urns of a loved one’s cremated remains.

So the burial custom may be dying. But that means, in a time of cultural change, planning a funeral is a moment of genuine opportunity. As the “how” of saying goodbye shifts, we can connect to a series of shared “whats” to help us navigate the moment of change with greater wisdom and compassion for all those saying good-bye.

Whether a bereaved family chooses in-ground burial, cremation, or another form of disposition, we all want to mark a loved one’s passing in a way that does three things:

– Makes sense, given the time and place in which we live,

– Honors the memory of the person to whom we’re saying goodbye,

– Affirms our enduring connection to that person in a loving and meaningful way.

Whatever funeral practice is trending up or down, if we relate to the ritual in that way – especially if other family members may not share our view on how to accomplish those three things – we can help each other (and ourselves) make it through a difficult transition with compassion and love.

Listed for many years in Newsweek as one of America’s “50 Most Influential Rabbis” and recognized as one of our nation’s leading “Preachers and Teachers,” by Beliefnet.com, Rabbi Brad Hirschfield serves as the President of Clal–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a training institute, think tank, and resource center nurturing religious and intellectual pluralism within the Jewish community, and the wider world, preparing people to meet the biggest challenges we face in our increasingly polarized world.

An ordained Orthodox rabbi who studied for his PhD and taught at The Jewish Theological Seminary, he has also taught the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs an ongoing seminar, and American Jewish University. Rabbi Brad regularly teaches and consults for the US Army and United States Department of Defense, religious organizations — Jewish and Christian — including United Seminary (Methodist), Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (Modern Orthodox) Luther Seminary (Lutheran), and The Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative) — civic organizations including No Labels, Odyssey Impact, and The Aspen Institute, numerous Jewish Federations, and a variety of communal and family foundations.

Hirschfield is the author and editor of numerous books, including You Don’t Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism, writes a column for Religion News Service, and appears regularly on TV and radio in outlets ranging from The Washington Post to Fox News Channel. He is also the founder of the Stand and See Fellowship, which brings hundreds of Christian religious leaders to Israel, preparing them to address the increasing polarization around Middle East issues — and really all currently polarizing issues at home and abroad — with six words, “It’s more complicated than we know.”