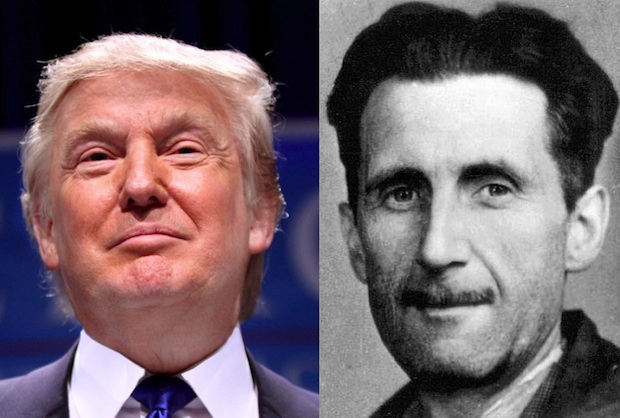

Donald Trump makes me think of George Orwell, but perhaps not for the reason one might expect. My association is not with the totalitarian state described in Orwell’s book, 1984, and its dictator, Big Brother. Rather, it is with the author himself, and the value he attributed to words, their import and the responsibility human beings have when using them.

George Orwell was first and foremost an opponent of using language in a sloppy or unthinking way. For Orwell, without clear and precise expression, there could be no clarity and precision in thought. And when thought becomes muddled, purposefully or otherwise, the worst kind of politics becomes possible.

It would be simple to use Orwell’s claims to indicate that our politics have descended to such lows that they indeed drag along with them just the type of vacuous and muddled discourse that he warned against. The obvious exhibit would be Mr. Trump, a man who despite holding a prominent position in his party’s electoral polls, espouses rhetoric that evokes the tenets of fascism. Yet, Orwell also warned against just this sort of unthinking simplicity in labeling political opponents.

According to Orwell, words that one would never apply to themselves must be used sparingly and with care. Fascism is precisely such a word. What is called for now is not only for voices to be raised in opposition to the noxious ideas that Trump articulates, but to do so without recourse to sloppy and unthinking language. Words like fascist only serve to provide more cover for those who would promote a worldview of “us against them”. Whether regarding terms like terrorism, radical Islam, fascist, or demagogue, the idea is not to avoid these words but to, in the words of Orwell again, “use [the words] with a certain amount of circumspection and not, as is usually done, degrade [them] to the level of swearword[s].”

This is not to say that strong words are not applicable in this context, nor is it to posit equivalences between the danger posed by different misuses of language. Rather, I feel it is important to emphasize that in communicating with each other about vitally important issues, we have a responsibility to add our understanding of the situation and not obfuscate it. Much of political discourse hinges on cliches and epithets, in some cases turning others’ political, religious, or cultural affiliations into slurs. The point here is not one about civility. Worse than the incivility of these terms is the way in which using cliches narrows the conversation and makes it possible to think or say less and less.

Orwell’s genius was to show how the way we use language and the politics we practice go hand in hand. How can language be used to expand and not shrink our vocabulary of reality? How can it be used to encourage, not dissuade us from engaging someone of a different view?

How, in our increasingly bifurcated society, can we recover our ability to speak to and about each other in a way that more effectively reveals what is at stake in our world and the challenges that lie before us?

Michael Bernstein, a Rabbi, has served since 2009 as Rabbi of Congregation Gesher L’Torah, a vibrant and dynamic Synagogue community in north Atlanta where each person’s story is embraced and Judaism is personal. He was ordained as a conservative Rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York in 1999. He and his wife Tracie have three children, Ayelet, Yaron and Liana.