In the category of “you can’t make this up, but wish you were” comes the story of Manhattan author, Justin Renel Joseph who is suing the Metropolitan Museum of Art, demanding that they remove “racist” paintings that depict Jesus as a fair-haired Caucasian. Specifically, the plaintiff seeks the removal of four works of art for “offensive aesthetic whitewashing” – itself a rather ironic term in this particular case – and the “extreme case of discrimination” created by their presence.

Mr. Joseph contends that the presence of such works of art create stress, and a sense of being “rejected and unaccepted by society”. Assuming he is being honest, and there is no reason to assume otherwise, nobody can challenge the authenticity of his feelings. They are just that, his. What can and should be challenged is their appropriateness and even more so, the remedy which he seeks to address them.

This is not, as Mr. Joseph charges in his suit, analogous to segregated lunch counters in the 1950s and early ’60s, in which people were barred from equal participation in public life. This is simply another case in which someone confuses appropriate cultural sensitivity and social responsibility with the assurance that their happiness and comfort in all situations is a civil right. He doesn’t like how something makes him feel, so it should go away. On that basis, in fact, we could probably make a case for closing pretty much all public displays of art.

He did get something at least partially right however, and it’s worth noting. In speaking to the New York Post, Joseph remarked that painters “completely changed (Jesus’) race to make him more aesthetically pleasing for White people”. I don’t know about completely, but to the extent that the story of Jesus comes out of the Land of Israel, it is at least more likely than not, that he was more tan than white. Of course, that entire debate is silly because it requires accepting the historicity of Jesus, which is hardly something upon which people agree, and certainly not the Met’s job to determine. I guess Mr. Joseph fails to appreciate any of that.

He is certainly correct that people tend to imagine their heroes and God as looking like themselves, and that is certainly the case when it comes to Jesus. It is why we have magnificent depictions of Jesus as Black by way of the Coptic and Ethiopian Orthodox Churches. And if Joseph had not sued for the removal of White Jesus’, but for the inclusion of some of those images, he may have had a point. But like so many people who wave the banner of inclusivity, they often prefer to banish what they don’t like, not fight for the inclusion of what they do. Sad, actually.

Ultimately, there is a positive take away here and it hinges on the importance of people having access to symbols which affirm them in lots of different ways and on many different levels. That does not mean that White people should only see White Jesus and Black people, Black Jesus. It simply means that at least some of the time, we all need to imagine our Gods, our heroes, our leaders and even our toys, as reflecting all of who we are. If they must always look like we expect, we are flirting with idolatry, but if they never do, it’s going to pretty hard for most people to make them their own. It reminds me of an exchange with one of my daughters when she was about four years old.

As we were concluding our bedtime prayers, my daughter looked at me and said, “I know who God is”. “Really?” I responded, “Can you tell me?” She said, “Yes I can. She is a 12 year-old girl who loves me very much”. I looked at her and told her that sounded just about right, gave her a kiss on the forehead and left the room. I think you get the point.

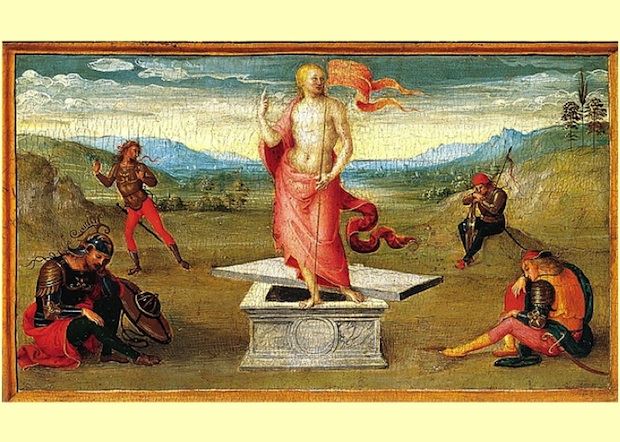

Image:?”The Resurrection” by Perugino, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Listed for many years in Newsweek as one of America’s “50 Most Influential Rabbis” and recognized as one of our nation’s leading “Preachers and Teachers,” by Beliefnet.com, Rabbi Brad Hirschfield serves as the President of Clal–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a training institute, think tank, and resource center nurturing religious and intellectual pluralism within the Jewish community, and the wider world, preparing people to meet the biggest challenges we face in our increasingly polarized world.

An ordained Orthodox rabbi who studied for his PhD and taught at The Jewish Theological Seminary, he has also taught the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs an ongoing seminar, and American Jewish University. Rabbi Brad regularly teaches and consults for the US Army and United States Department of Defense, religious organizations — Jewish and Christian — including United Seminary (Methodist), Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (Modern Orthodox) Luther Seminary (Lutheran), and The Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative) — civic organizations including No Labels, Odyssey Impact, and The Aspen Institute, numerous Jewish Federations, and a variety of communal and family foundations.

Hirschfield is the author and editor of numerous books, including You Don’t Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism, writes a column for Religion News Service, and appears regularly on TV and radio in outlets ranging from The Washington Post to Fox News Channel. He is also the founder of the Stand and See Fellowship, which brings hundreds of Christian religious leaders to Israel, preparing them to address the increasing polarization around Middle East issues — and really all currently polarizing issues at home and abroad — with six words, “It’s more complicated than we know.”