The Shabbat before Purim, this last Shabbat, is called “Shabbat Zachor,” because during it we read a special additional Torah reading describing Amalek’s attack on the Israelites:

Remember what Amalek did to you on your journey, after you left Egypt—how, undeterred by fear of God, he surprised you on the march, when you were famished and weary, and cut down all the stragglers in your rear. Therefore, when your God grants you safety from all your enemies around you, in the land that your God is giving you as a hereditary portion, you shall blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven. Do not forget! (Deuteronomy 25:17-19)

Haman is considered to be a descendent of the Amalekites, and so our tradition links the story of the Amalekites attacking the Israelites in the time of the Exodus to our blotting out Haman’s name with noisemakers on Purim.

The above piece from Deuteronomy describes a particularly confusing commandment, difficult to parse in English or even in Hebrew. We usually remember to remember, or we forget to remember; we don’t usually try to remember to forget something.

Why would we need to remember to forget something? First, let’s look at what we are told to blot out. The people of Amalek attack the Israelites as they are making their way, exhausted and thirsty, after the splitting of the Red Sea. The battle is described in Exodus 17:8-16. The Amalekites, according to the verses in Deuteronomy, attacked the rear of the Israelite march, which is where the weakest of the group are. They killed the women and children. The sick and the elderly. They targeted them on purpose. They showed no mercy. It was a trauma seared into the Israelites’ memory.

It was a Terrible Thing—something you don’t easily recover from in your life. Something that is a touchstone, a turning point; something that changes things forever. This kind of trauma, this kind of affront to decency and shattering of our sense of security: We hold on tight to the memory. We say, “Remember what they did!” We say, “Never again!” We witness. We testify.

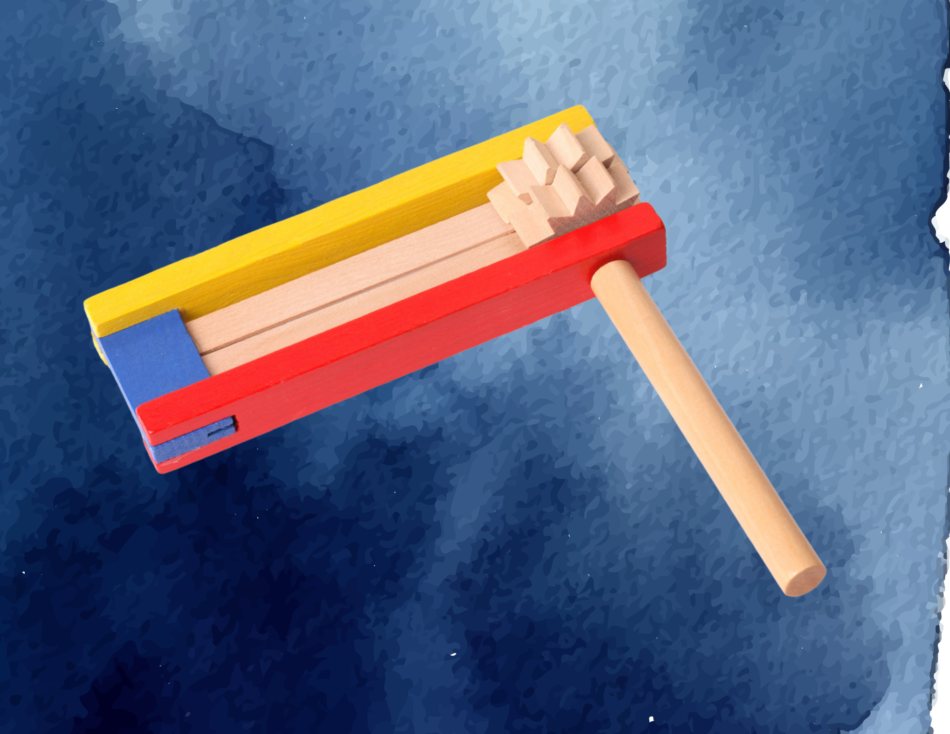

However, we are told in the Deuteronomy passage to blot out the Amalekites. To forget them. To make sure no one remembers them. So, we fight people who want to remember the perpetrators as glorious and just. At the same time, we ourselves may still hold tight to the memory of The Terrible Thing while we blot it out, in clenched fist. We shake, shake, shake that grogger, gripping it hard, to drown out Haman’s name. We yell; we boo. This is not really forgetting.

The deep truth of Purim is connected to the fact that it’s a celebration after an almost genocide. It’s a different quality of celebration than a light-hearted night out. It’s the celebration that comes after surviving The Terrible Thing.

Rebbe Nachman taught, “It’s a great mitzvah to be happy all the time.” It’s important to remember that Rebbe Nachman was a sad person who struggled to find joy. They say rabbis write the torah they most need to hear themselves. This teaching is not a statement of obligation; it’s a prayer. A prayer to be able to be happy.

I’m feeling the Amalek portion this year a bit differently. What is the forgetting we need? I deeply feel all the instincts to hold on tight to the traumatic memory, to insist that it not be forgotten. Let’s turn deeper inwards, though, to our own spirit, our neshama: What if we do indeed need to remember to forget, sometimes? To put down the grogger? To put down the phone, the videos of kidnappings, the petitions, the protests on campuses and counterprotests, the news articles, the fights in city council meetings? To put it down and remember to forget The Terrible Thing, just for a moment, so we can practice living in a place of abundance and joy? With the topsy turvy nature of Purim, maybe it’s both “Never Again!” and also, at the same time, “Remember to forget sometimes!”

It is a balance. Sometimes we do need to remember to remember. Sometimes putting The Terrible Thing out of our mind entirely means we aren’t able to metabolize it and turn it into a regular memory, which leaves it radioactive and it continues to harm us.

This week marks the fifth anniversary of the shutdown of the world and the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. Some states and countries have created a national day to remember the pandemic, but most have not, and public observances are uneven. I might have expected a national televised memorial service honoring the dead, the orphans, and the heroes. It seems that some people are ready to remember, and some are still trying to forget. The World Health Organization estimates at least 7 million people died of Covid-19 worldwide, probably many more. In New York City alone, 900,000 people lost three or more loved ones to Covid. I myself can barely look at the pictures or call up the memories.

Remember to remember and remember to forget. They are both present in this Purim precursor in Deuteronomy. Our task is to discern when is the right time for each one. That’s maybe why the commandment is so confusing (Remember! And also forget!) When it comes to The Terrible Thing, we may need to do both.

Rabbi Julia Appel is Clal’s Senior Director of Innovation, helping Jewish professionals and lay leaders revitalize their communities by serving their people better. She is passionate about creating Jewish community that meets the challenges of the 21st century – in which Jewish identity is a choice, not an obligation. Her writing has been featured in such publications as The Forward, The Globe and Mail, and The Canadian Jewish News, among others.