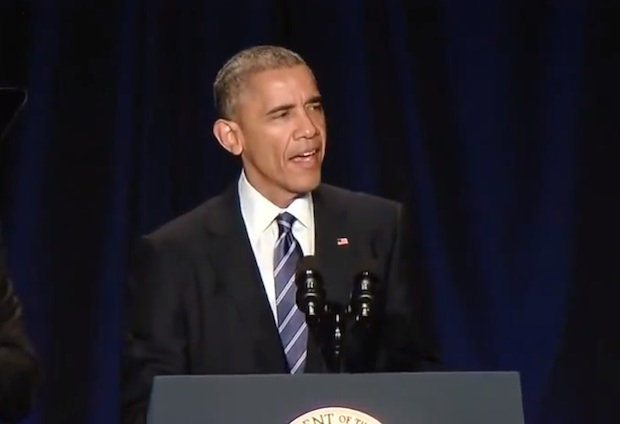

When I’m wrong, I admit it — at least, I try to. My first gut reaction to President Barack Obama’s controversial remarks at last week’s National Prayer Breakfast was both right and wrong; so was Mr. President. I’ll explain what I mean.

My first response was unreservedly positive, both off the air and when I appeared on NewsmaxTV to offer commentary. But I was wrong not to challenge the warning that we shouldn’t “get up on our high horse” criticizing the horror of radical Islam.

The President is certainly correct about this fact: All faiths have had blood on their hands at some point in history. In fact, every faith has been used to justify some terrible things, which the faithful came to regret years later. That insight is not only true, but has real moral and strategic importance. More on that below.

And I appreciate that the President probably meant: No community should pretend to be without sin when it comes to its use of faith. Again, he’s 100% correct. His admonition suggests, however (or at least is being understood by many to mean), that the current condition of all global faith communities is equal — I believe that to be totally false — or that, because of past sins, no community can raise a voice of moral conscience about the horrors done in the name of another tradition. I find that dangerously absurd. Accepting such an argument would lead to a kind of paralysis, and a tolerance of the death of untold innocents.

Americans have every right to get up on our high horse, precisely because where America is generally (and where contemporary American Christianity is more specifically), there’s no comparison to be made with radical Islam. Americans are far from perfect. And that should be acknowledged. Although his comments require clarification, I don’t think the President was attempting to create false moral equivalence.

President Obama’s remarks were actually a corrective on his past refusal to name radical Islam (as opposed to amorphous “extremism”) as the engine driving the global terror we are fighting. Since it’s hard to effectively fight what cannot even be named, he was right to do that.

Furthermore, by openly admitting historic atrocities committed in the name of Christianity, he was creating the ethical context which demands that Muslim leaders engage in the kind of public soul-searching that the President was modeling. In effect, our President finally threw down the gauntlet to all those who suggest that the problem has nothing to do with religion/Islam, but is instead strictly a function of culture, economics, or who knows what. All of those are factors, yes. But when the last thing that hundreds of thousands of victims hear just before their deaths is “Allahu Akhbar,” that’s a problem with the use of one particular tradition – and we dare not ignore that fact, however painful it may be for some.

The Prayer Breakfast comments were appropriate precisely because they made people uncomfortable. Self-critique and genuine humility create the moral ground from which we can criticize others and legitimately fight against them. We hold out no pretenses of our own perfection, but neither will those past imperfections be an excuse for fighting contemporary horror.

The burden is now squarely on those who confuse support for Islam with dangerous apologetics. They must allow themselves to feel as honest and uncomfortable as many good Christians may be after hearing the President’s history lesson.

The willingness to hear that lesson is what gives us the right to demand that others do the same, with respect to their tradition. If they will not rise to that challenge, then – whether they admit it or not – they carry a real measure of responsibility for what’s being done in the name of their religion.

These remarks of the President’s have lifted the conversation out of an unhelpful debate about who’s inherently better. Instead, his comments bypassed that debate for the only important question: Is the tradition you love being used for life or for death, for coercion or for liberty, for love or for hate?? That’s how we should judge ourselves in this country, and how we’ll judge others as well.

Listed for many years in Newsweek as one of America’s “50 Most Influential Rabbis” and recognized as one of our nation’s leading “Preachers and Teachers,” by Beliefnet.com, Rabbi Brad Hirschfield serves as the President of Clal–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a training institute, think tank, and resource center nurturing religious and intellectual pluralism within the Jewish community, and the wider world, preparing people to meet the biggest challenges we face in our increasingly polarized world.

An ordained Orthodox rabbi who studied for his PhD and taught at The Jewish Theological Seminary, he has also taught the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs an ongoing seminar, and American Jewish University. Rabbi Brad regularly teaches and consults for the US Army and United States Department of Defense, religious organizations — Jewish and Christian — including United Seminary (Methodist), Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (Modern Orthodox) Luther Seminary (Lutheran), and The Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative) — civic organizations including No Labels, Odyssey Impact, and The Aspen Institute, numerous Jewish Federations, and a variety of communal and family foundations.

Hirschfield is the author and editor of numerous books, including You Don’t Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism, writes a column for Religion News Service, and appears regularly on TV and radio in outlets ranging from The Washington Post to Fox News Channel. He is also the founder of the Stand and See Fellowship, which brings hundreds of Christian religious leaders to Israel, preparing them to address the increasing polarization around Middle East issues — and really all currently polarizing issues at home and abroad — with six words, “It’s more complicated than we know.”