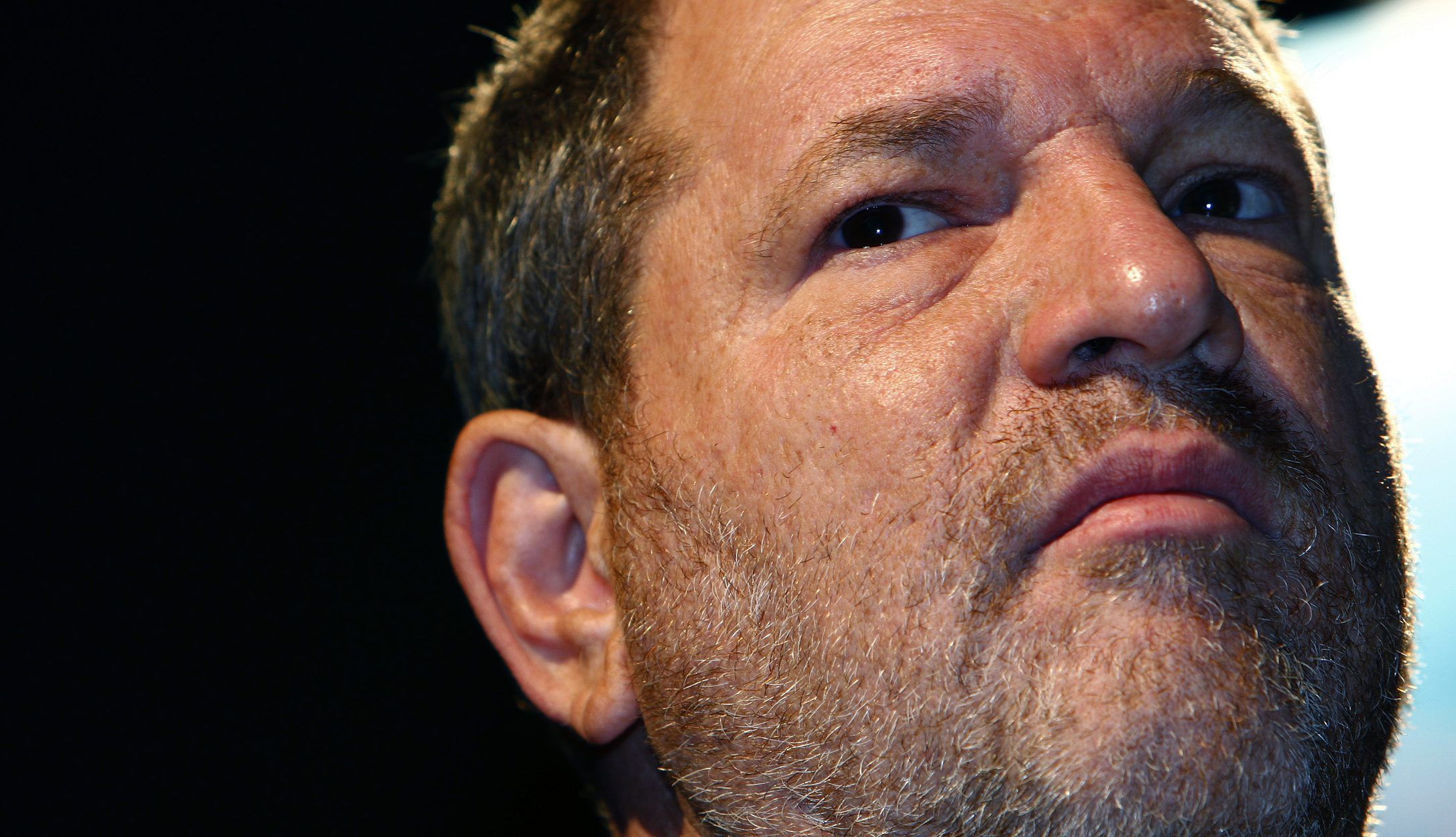

When reports of Harvey Weinstein’s predatory behavior surfaced, a memory of a decades-old sexual encounter sprung like a toxic weed from my subconscious. I’d been about the same age as some of the actresses were when Weinstein allegedly harassed or assaulted them. To take the pulse of the moment, I read comments on the flurry of articles to see if society had made any progress around women’s believability. Distressingly, many claimed that actresses should have spoken out immediately, that waiting decades to come forward is cowardly or opportunistic, or that they should have known better than to go to his hotel room.

At that age, my legal right to drive a car, vote and purchase alcohol did not, contrary to conventional thinking, bestow me with the full arsenal of skills needed to navigate the so-called adult world. At 22, despite my degree in mathematics from an elite women’s college, I had barely been schooled in the exasperating, infuriating and even humiliating Catch-22 of being female in a patriarchal culture. I did not yet know the extent of the insanity, that regardless of what I wore or didn’t wear, or what I said or didn’t say, or what I did or didn’t do, I could still be vulnerable to unwanted attention if not predation and, if I did not handle myself impeccably, be exposed to judgment and shaming.

I was not totally clueless, however, about the strangeness of society. I knew young women who’d been romantically involved with their high school teachers and I might have, too, had my mother not intervened. One professor at my alma mater, meant to empower women, had a reputation for sleeping with his students. A friend whose parents pressured her to marry sowed her wild oats on the sly. It was the rare peer who enjoyed her libido in what seemed like a healthy manner. Despite the limited evidence of such a possibility, I wanted to believe I could outmaneuver compromising situations while exploring romance. I wanted to believe I could spot a schmuck from a mile away and silence sleaze bags with a sharp retort.

After college, in the summer of 1989, I packed two suitcases and moved to Budapest. My story was that I wanted to gain international experience and continue to learn the language, which I’d begun studying there my junior year. That semester, I’d met a young man who fell in love with me, a nerd increasingly self-conscious about being a virgin. His steady letters and phone calls during my senior year felt like a rope to grasp as graduation loomed and my parents’ divorce left me confused and heartbroken. He insisted I had returned to Hungary, where my father had been born, to be with him. Parroting my college lingo, I believed I was a “cussed individualist” who’d forge her own destiny. If he wanted to come along for the ride, great! Certainly I was too much of a cussed individualist to consider his perspective.

I looked in the classifieds and saw two promising jobs. One was for an assistant at a brokerage house. The other was for a writer and translator at an English language monthly. The magazine paid less but offered cultural immersion. I found a studio apartment with a rare telephone line and, on the first night of my independent adult life, locked myself out. After that embarrassing start, I began working in the newsroom, located in a small house outside the city center.

A group of secretaries occupied the foyer, protecting other staff from distractions. When they weren’t answering the phone, they sucked on cigarettes, gossiped and drank coffee. Like others in the socialist economy, they lacked a sense of industry but responded to flattery. An overachiever, I didn’t know how to connect with these women.

My bearded British boss chain-smoked in the open office as he edited copy across from where I sat. He overwrote much of my work with a blue pen. I did not take the corrections in stride. I argued over points of grammar, absurdly defending my American prepositions for a periodical with British readers. I couldn’t admit I had no idea what I was doing. I didn’t readily grasp politics or economics. I didn’t know what made a good story. I stubbornly clung to my syntax because I needed to grasp something. My lofty vision for myself, incubated in an ivory tower, had disintegrated and become as hazy as the air around me. The bookkeeper, a plump woman in her 50s, sensed my disorientation. She suggested I go home, find a husband and have children, in her opinion the only lasting source of satisfaction. She might as well have told me to cut off a limb.

A few months later, an American male journalist, probably half a dozen years older than I was, appeared in our slow-paced, smoke-stained workplace. Unlike my mellower European colleagues, he carried himself with the energy and vigor of someone who believed he had the right to be anywhere and do or say anything. He met with the magazine’s top editor, a distinguished older man who showed up infrequently. At some point the editor’s voice changed tenor and he stiffened and leaned forward in his chair. Had the visitor demonstrated ignorance or wasted the boss’ time? The meeting ended. Somehow, I ended up having dinner with this reporter. Was that because none of my colleagues could make it or they didn’t want to? Had I, feeling homesick, suggested it? I don’t remember.

I can’t tell you if this writer got the scoop he’d come for, but over dinner he scoped me out. By then, I was no longer a virgin, but intercourse had not magically transformed me into a mature woman or a satisfied one. I was still dating my boyfriend but I wondered if, in making a safe choice, I had sacrificed sensuality. The journalist’s direct gaze and overtures flattered me and made me a bit fearful. Compelled by a mixture of curiosity and dread that seemed to temporarily dissolve the black-and-white proscription against cheating, when he invited me to his hotel room, I went.

As much as I enjoyed flirting with men and fantasizing about them, I had little experience following through. The follow through, in this case, left me feeling deeply ashamed. I had become mute, putty in his more experienced hands, unable to speak up to slow things down to my pace. That he had been smooth and slick, a bit too practiced, made me feel sick. In today’s parlance, I had been a booty call during his boondoggle. He asked if I wanted to spend the night but I quickly dressed and got out of there.

To ease my distress and address my cognitive dissonance, I created a narrative: because I had gone to this man’s hotel room, it proved I didn’t want to be with my boyfriend anymore. Shortly thereafter, I broke up with him. Indeed, I had wanted to end the relationship, but I couldn’t admit it to myself or say so to him. Wasn’t I, a nice Jewish girl, supposed to stay… forever? To leave a man for no “good reason” made me doubt myself. How to explain my vague dissatisfaction to the patriarchal jury in my head, biased towards respectability and settling down? Wouldn’t I have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that this man was a jerk? Because I could not answer that jury or, even better, evict it from my psyche, I had to “misbehave”, become the jerk, and therefore give myself an excuse to leave. That story restored some agency and allowed me to move on, or so I thought.

After I returned to the United States, contrary to my wish that “what happens in Budapest stays in Budapest”, revulsion and shame engulfed me when this journalist’s name periodically popped up. That he’s a political conservative, which I doubt I knew then, doubled my disgust. That he’d become a columnist, paid for his opinions, sparked my fury. Why did I still struggle to not only find words but also to be heard, believed and respected? That he’d married meant some woman found him trustworthy and he could bask in the glow of social respectability. That I hadn’t found a man I both desired and trusted filled me with despair. As time passed, the memory again sunk into the recesses of my mind, seemingly for good. But when his name showed up in my Facebook feed a few years ago, I recoiled, then silently cursed him. Why was I upset?

Last week, the myriad stories of harassment, abuse and unwanted advances shared online shattered the silence and created an emotional safety net, giving me the courage to face my vulnerability. That long ago encounter, while not violent, had nevertheless been violating. Being confronted, especially while naked, by my utter naïveté and inability to speak when I wanted to must have been more devastating than I allowed myself to believe. At the time, I did not understand that my not being a Wonder Woman with the wherewithal to fearlessly handle every life situation did not make me defective. Like others who’d found themselves in unexpected situations, I had frozen. That many people still would like to use that normal physiological response against women, to claim that silence implies consent, is a way of saying that women aren’t allowed to be human, they must be superhuman, to be valued and heard.

Indeed, the shame and habit of keeping quiet run so deep that, even after a friend and reader sent me a private message asking if I’d write about Weinstein, I hesitated. Others had tackled his behavior directly. Mine was neither a sensational story, nor a cut and dry situation. Did I want to spend a beautiful fall day, if not more, dredging up memories about what some might dismiss as a harmless one night stand, as if I’d lost a casual tennis game? As I deliberated, I cautiously cracked open my journal from that year to see if I had recorded details. Not a word at the time, but months later, I’d scrawled, “Ugh…I will never do that again.” That’s it. That I had written about other distressing things made me suspect I’d been too mortified to put it on the page for my future self to find, as if the younger me didn’t trust that who I am today would be understanding.

My decision to write this essay and try to unpack that ancient “ugh” unleashed a litany of critical voices: “Without more details, you shouldn’t put this out there”; “Forget about it and move on”; “Do you want people to know about your stupidity?” That these voices echoed some of the less enlightened responses to the Weinstein revelations made me realize I needed to find my own words as an offer of compassion to my younger, confused self. Now I finally see that the poisonous weed was not just the episode but the relentless self-recrimination I’d attached to it. It’s about time I yanked it out of my life. For a long time, I couldn’t.

Ilona Fried is a writer and student of the Feldenkrais Method. Her articles and essays have been published at The Huffington Post, Elephant Journal, and Hevria. She blogs about awareness and spiritual practice at alacartespirit.com.