Friends have warned me that my mind is so open, my brain might fall out. Often, they cringe when I don’t slam an opinion or philosophy that seems to go against everything a smart person should think. That woman across the street who claimed that faith in Jesus’s divinity is the one trait that will lead to eternal bliss after death. The guy I met on a plane who thought every single adult American with no history of psychosis or criminal violence should own a gun “just in case some nutcase shows up.” The boy in my high school who contended that anarchy was the way to go — no police force, laws, prisons, or government. Who was I to say they were wrong? It felt crazy to step up and say: “My mental universe understands better than yours. I know that’s true, even though I’ve never spent time in your mind, soaking in its nuances and particular patterns of thought.”

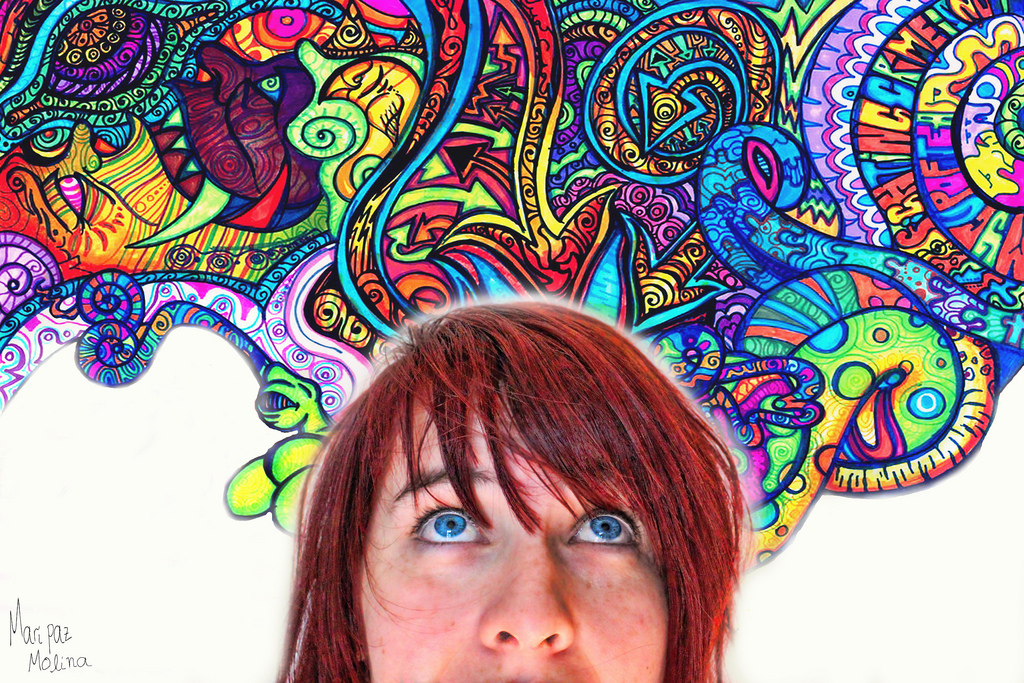

I did argue. Arguing to me is a sport, an intricate fencing match with brains instead of swords. I like arguing, but not because I know I’m right. Honestly, I’m never sure of that. When I argue, I draw other people out, push them to go deeply into their ideas, assumptions, speculations, and values. I say one thing, but when you insist on another, I listen. I bring your perceptions into my own intellectual world. Even if I don’t change my mind, I can conceive of changing my mind. And I think that’s key. When you can conceive of changing your mind, you begin to open your imagination to all the vast mental spaces that aren’t yours. You respect that the cognitive landscape you inhabit is expansive but limited. Another consciousness might have a line into different insights from yours.

My grandfather used to say: “Everything in moderation, even moderation.” I loved that line, because it meant that, occasionally, I could stuff myself with fistfuls of fried Creme Eggs or piles of fried tongue (don’t knock it till you’ve tried it). Even openness should be practiced in moderation. I draw the line at viewpoints espousing cruelty, meanness, and evil. It gets tricky; what’s cruel to one mind is perfectly ethical to another. I’m just saying that even I have a limit when it comes to open-mindedness. Tell me you believe your uncle Joe is the Messiah, and I’ll hear you out, because why not? You know your uncle Joe; your mind has sensitivities and abilities that mine lacks; maybe you see something that’s completely escaping me. Tell me you’re planning to strangle your uncle Joe to death because his jokes annoy you, and I’ll do what I can to stop you, because you’re crossing my basic threshold for ethics and decency.

Even so, I’ll listen to your reasons for your plan. If you tell me why your uncle Joe’s jokes bother you enough to take such a step, surely I’ll learn something if I don’t shut you out. Your mind is still a mind, your internal world still a hive of breathtaking complexity. I’ve never planned to kill anyone because of bad jokes. If you have, your brain is going places mine hasn’t reached on its own. Maybe you can take me there at least part way — not to stay, just to glimpse how it feels to be you.

You could say that I have many minds, and they move in all kinds of directions. This allows me to spend time with all kinds of religious and spiritual groups, entertaining their notions but never becoming one of them. Those evangelical Christians from college who pored over every word of the New Testament because they believed it was the infallible word of God? The ones who projected I’d end up in an eternal hell cut off from God unless I came around to Christian faith? I hung out with them, singing songs about Jesus and sipping hot chocolate in their leader’s dorm room. Why? Because they were a tight-knit group, united in their faith that God created and infused every possible thing. I found that glorious. They saw themselves as a band of outsiders on a campus that didn’t understand them, and I loved the coziness of it all, the love shared among friends trying to get by in a misguided world. Most important, they knew they were immortal — that their souls, hearts, and minds would survive physical death.

This didn’t eliminate most normal stresses: they fretted over papers and stewed about their medical school applications. But they walked around envisioning and embracing eternity, sensing it in the grass as their shoes slid over it. They were the first people I’d ever met who didn’t assume death would end their mental worlds. The door they opened in my mind led to the most healing possibilities. I couldn’t accept the black-and-white aspects: that one book was infallible, or that one specific belief separated the eternally blessed from the eternally damned. But the deeper, more fundamental idea that we are more than our brains and our bodies — that something spiritual undergirds it all, giving us power, meaning, and purpose beyond the surface details, and that death is a portal to a new and fabulous realm — soothed and galvanized me.

Since then, I’ve spent time with many spiritual groups, culling whatever melds well with my hungry but cautious spiritual quest. Lubavitcher Hasidim. Out-of-body explorers. New-age mystics. Near-death experiencers convinced they’ve touched the realm they will enter when they die for real.

And I’m always open — except when I’m not. I hate to admit it, but sometimes my mind closes off, stewing in its own snobbery or disappointment. Lack of intelligence, narrow-mindedness, brimming confidence, and personal ambition tend to turn me off with this stuff. The summer of 2014, I attended a conference in Phoenix, run by the Academy for Spiritual and Consciousness Studies. This organization focuses on afterlife research, and, given my deep desire for individual consciousness to continue after death, is a seemingly perfect fit for me.

I don’t like to discuss people publicly unless I’m saying all good things, so I won’t mention any names here. Let’s just say that some anonymous dude at this conference was getting touted all over as a kind of grandfather of afterlife research. Let’s say, further, that I dredged up the nerve to talk to him, and he was extremely receptive. He really was charming, and open to short, awkward me.

He told me to read his books, because he was sure they would give me my answers about soul survival after death.

Me: “You think I’ll have no further questions, because your books are that convincing?”

Him: “If you go in with the right mindset, yes.”

Well, I suppose I went in with the wrong mindset. This happened not only because, as usual, I could think of all kinds of alternate explanations for his experiences — ones that had nothing to do with consciousness surviving death — but because I didn’t like his feeling that his books were the be-all and end-all on this subject.

So many brilliant and sensitive minds have tackled this topic through the centuries. He was sure that his books in particular would convince me, after I told him I’d done all kinds of reading and spoken to many intriguing souls and still had my doubts? This level of self-assurance gives me the heebie-jeebies. If he’d been more like: “I did make my own humble contributions to this field, if you’d like to take a look. I can tell you that a lot of thought went into these projects, and they were very heartfelt”… my attitude would have improved dramatically (though his work had enough potential holes that I’m sure I’d still be a basket case whenever the thought of dying crossed my mind).

Sometimes — I’m not sure how to put this diplomatically, so I’ll just be my blazingly honest, crude self — spiritual leaders and alleged experts don’t seem bright to me, and I feel my mind twisting in scorn. At a conference on near-death experiences several years ago, one of the presenters didn’t seem to understand my questions about the continuity of consciousness from life into the afterlife phase she was describing.

Me: “You say that your energy will persist after death, but does this mean that your consciousness will remain intact? Will there be an awareness that has continuity with the awareness that is now experiencing this conversation?”

Her: “I don’t really get your question, Hon. My brain hurts right now, ya know? All you need to remember is that your energy won’t die.” She spoke with an interspersed giggle and a harsh, grating accent, and I just could not take her seriously.

And of course it’s more than OK to be skeptical in this world. With no skepticism, we’d be broke, miserable, and crushed by all who would feed upon us. Outsized confidence in the realm of spirituality may be a true red flag signaling caution. That conference presenter who told me his books provided ultimate answers that were beyond further questions had fawners following him around and praising his work beyond the skies. He had that scary kind of charisma that reminds me of cult leaders, dictators, and poisoners of atmospheres in schools around the globe.

The line between confidence and arrogance is tricky and hard to pin down, but I felt in my soul that he had crossed it. Intellectual haughtiness strikes me as the opposite of wisdom. It’s the feeling that your mental world is unassailable, impervious to infusions from all the other gorgeous human minds that thrive on this earth. If there is such a thing as truth, the arrogant seem more likely than most to lack it, mired as they are in their own puffed up mental space.

At the same time, I should probably cultivate a bit more openness when people seem to lack standard intelligence. Isn’t my fondest hope that we are more than our brains and bodies — spiritual beings who far transcend the brain’s limitations? If we do transcend our physical brains, some who struggle with standard intellectual processing might have other gifts, channeled through means we haven’t yet defined or measured.

Years ago, at a family party, my cousin with longstanding intellectual challenges looked at me and said, with no particular prompting: “You think you’re tough, but you’re really just a big softy.” I remember thinking that this comment hit the absolute center of how I was feeling. There was no logical reason for my cousin’s remark; she just outed with it, like she tends to do. I hadn’t said much to her, and she had no reason to know anything about my mental state at the time. I had an immediate hunch that she enjoyed a kind of insight most people don’t share, that perhaps she’s not “slower” than most; she just has a vastly different way of perceiving and gaining knowledge, and sometimes, she’s the one with the superior wisdom.

Likewise, maybe the presenter who turned me off is downloading information and sensations I can’t access, and she feels them in some kind of psychic space I can’t begin to imagine in my current state. True, my standard reasoning ability probably beats hers, but that’s just one facet of mental experience. From her perspective, I have spiritual blind spots; from mine, her ability to reason and process information feels weak. She enjoys supreme joy and peace; I am a lunatic who obsesses about death’s inevitability and the passage of time.

Who is smarter in an ultimate sense? The question makes me shiver. And makes me realize once again that my mind is rich and complex but limited, and if I want to learn, grow, and prosper in my soul, I need to let other minds’ perceptions mix with my own. My mind is as open as a shining noontime sky: a clear one where nothing falls out but healing rays that the sun won’t miss.

Stephanie Wellen Levine is the author of Mystics, Mavericks, And Merrymakers: An Intimate Journey Among Hasidic Girls: winner of Moment Magazine’s 2004 Emerging Writer Book Award. Currently, Stephanie is on a spiritual quest as she completes a second book and teaches at Tufts University.