My grandmother is an artist. Growing up, I would go visit her in her studio. Set up all around the room were projects in various stages of completion. She did her own work as well as taking commissions for portraits and other scenes for clients. But the surfaces weren’t just covered in canvasses; near many of the canvasses in progress were sketches, small watercolors, parts of figures, and scenes. These were her studies: the initial renderings an artist makes as she is testing out her method or composition for the final masterpiece.

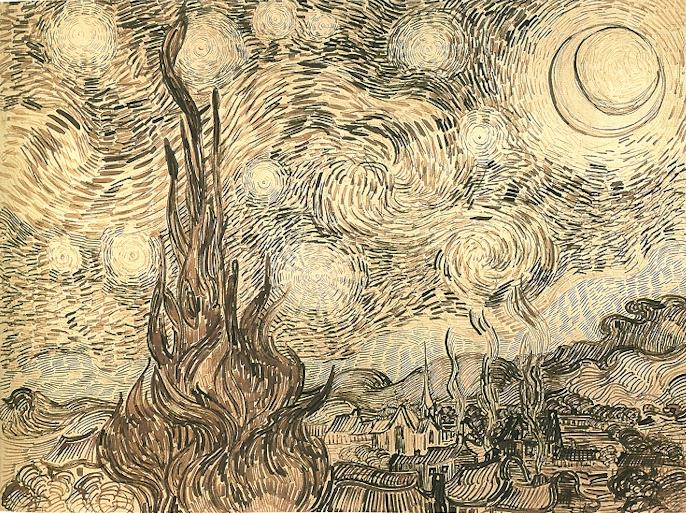

You can see these sketches by famous artists in museums, especially in retrospectives featuring a large collection exploring their work over time. Georgia O’Keefe painted sometimes from Polaroids she took of the New Mexico desert. Diego Rivera, the great Mexican muralist, drew notepad-sized sketches of his murals before mapping them out on the grand walls that were his canvas. Even Vincent Van Gogh’s famous “Starry Night” – an image indelibly inscribed in our memories from college dorm walls or souvenir mugs – had first drafts, one of which is preserved in brown and black pencil.

Jewish communal professionals of all stripes often feel the pressure to put out a perfect “product.” We feel we must be the genius off in the board room, coming up with brilliant ideas and solutions to the community’s problems right out the gate. We think hard and then take a stab at it, but often fall short, and we feel we have failed.

After spending a lot of my student rabbi years and early rabbinate trying to fulfill the expectation that I am the one who can solve it all myself, I now teach that we need to start small, with a sketch, a prototype. After taking the time to understand our people and what they want – a step often skipped for time – we want to put out a prototype and see where it goes. What will we learn from feedback? What can we improve? How can we center our people’s needs as we create this offering? How can this idea continue to grow until it comes to full fruition?

This week’s Torah portion, Kedoshim, includes the laws of first fruits. When planting an orchard, we are not to use the fruit for the first three years. In the fourth year, we harvest and dedicate to God by bringing it to the Temple in Jerusalem as an offering. Only in the fifth year do with reap the fruit for ourselves.

In the Jewish communal world, we feel pressure to fill the calendar, always going, always producing events and programs. However, we are sometimes harvesting before things are ripe. What might it look like to allow ourselves more time to cultivate our ideas, to let them be shaped by the sunshine of feedback and nutrients of collaboration and co-creation with our people? We will have fewer fruits at a time, potentially, but each one will be far more delicious.

Rabbi Julia Appel is Clal’s Senior Director of Innovation, helping Jewish professionals and lay leaders revitalize their communities by serving their people better. She is passionate about creating Jewish community that meets the challenges of the 21st century – in which Jewish identity is a choice, not an obligation. Her writing has been featured in such publications as The Forward, The Globe and Mail, and The Canadian Jewish News, among others.