I have long been fascinated with the concept of ‘beshert,’ which translates from Hebrew to English as ‘destined’ or ‘intended,’ or meant to be. It ties into what I think of as the Hansel and Gretel breadcrumb trail that winds inexorably from past to present. I grew up in Willingboro, NJ which is a suburb of Philadelphia. Our family attended services at Beth Torah which was a Conservative congregation. For many years, I sat in Sunday school and Hebrew school classes, where I learned the traditions and language of our culture and religion. One of my teachers, who also coached me in reciting my Haftorah in preparation for my Bat Mitzvah, was Richard Simon. He felt more like a peer than the somber elders who had instructed me before. He was lighthearted and made learning fun.

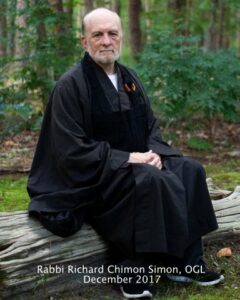

We were out of touch for many years and then through the marvels of modern technology and a place in cyberspace called Facebook, we reconnected. A sad event brought us together, which was the September 2014 death of a mutual friend named Delane Lipka who owned a retreat center in Washington, NJ called Mt. Eden. Her service was held on the grounds and Richard, now a rabbi, led it.

Almost 10 more turns of calendar pages happened and I heard that he would be offering a weekend of events at Temple Judea in Doylestown, PA. Since he was in my neck of the woods, I knew I had to be there. He spoke about the Kabbalah and practical spirituality. This was the bashert aspect. I sense that I met Richard in my youth, so that as I am in my elder years, I can deepen my spiritual practice. I was touched by something he said as he began speaking. He honored my father as one of his teachers. My dad was not a rabbi, nor a trained teacher of Judaism. He was a life long learner, who lived his religion, practicing Tikkun Olam. I sensed my dad would be kvelling, watching Richard doing what he does best, opening the door to exploration.

Please share a bit about your upbringing and the role Judaism played in your early years.

Please share a bit about your upbringing and the role Judaism played in your early years.

I was raised in a Jewishly Conservative home. My father’s parents were Orthodox. My other grandparents were Reform. I attended yeshiva (Jewish school) at an early age and was one of those strange kids that really enjoyed it! I excelled at Hebrew and Torah. But I also experienced a very “personal” relationship with God, talking with God from an early age. This sometimes alarmed my parents! But when asked about God, my religious grandfather would tell me, “God’s the one that’s going to punish you if you mess up.” I decided at an early age that I didn’t want anything to do with that “unloving” God, and thus began my foray into other religions.

Was there a pivotal moment when you decided to embrace the career path of ordination as a Rabbi?

I was studying with a non-Jewish spiritual teacher who told me it was my destiny to be a rabbi. I didn’t believe him. Because of my good Jewish education, I would teach and lead services at local synagogues. On one Saturday morning, while leading Shabbat services, I had a “calling.” It was an unmistakable feeling of “this is what I should be doing.” At the time I was studying with some rabbis, including Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi in Philadelphia. When I approached him about my choice, he smiled and said, “I’ve been waiting for you to figure it out!” Thus began my rabbinic studies under his tutelage and other rabbis. I was ordained by three rabbis in 1985 and immediately was hired by a synagogue in Mt Holly, NJ, where I remained for 32 years. In that time I have served as a teacher and spiritual director for a few hundred students in various forms of mysticism, mostly Jewish.

How has your practice evolved over the years?

I started as a typical Jewish adult practice of study and prayer, always looking for ways to continue the Awareness of the Divine in my everyday life. At 17, I learned to meditate (from a magazine article!), and shortly after that met people that were studying various forms of spirituality. My practice was mostly meditation and prayer, eventually adding martial arts and yoga. I continued my study and practice of Kabbalah, and supplemented this with other practices (see teachers and mentors listed below). My current practice is mostly a Zen approach to Judaism, but I am still teaching Kabbalah and other forms of mysticism.

When did Buddhism enter into your life?

In 1990, I attended a local clergy retreat where I met Brother Stephen Reichenbach, who was teaching spirituality on behalf of the Catholic Diocese of Trenton. He had studied Zen Buddhism in Asia, and opened a Zen Monastery in Riverton, NJ. Brother Stephen soon became Seijaku Roshi, and we became fast friends and “spirit buddies.” When we first met, I asked him for a personal Zen practice. He closed his eyes for a while and then proceeded to tell me that I should follow a traditional Jewish prayer practice, including Zen meditation. I asked him why it had to be a Jewish practice and he answered: “You’re a rabbi, right? Zen is about being who you truly are. Judaism is your practice, done with Zen Mind.”

I know many whose root religion was Judaism who consider themselves practicing Buddhists. Can you please clarify the idea of Buddhism being a philosophy rather than a religion such that it is not exclusive to other practices, such as Judaism?

This is a common misconception, especially among Americans. For most Buddhists, Buddhism IS a religion. In fact, it is the fourth largest religion in the world. And most Buddhist practices involve worshipping a deity (usually one or more Buddha figures or other divine beings). I would have a hard time being part of this religion, given Judaism’s insistence on One God and abhorrence of worshipping figures (idols). Zen Buddhism is the exception. It was brought to Japan in the 13th century, about 1,800 years after the Buddha taught in India and didn’t arrive in America until the end of the 19th Century. The Hindu Yogis called it “dhyana;” in China it was “Ch’an;” and in Japan it became “Zen,” All of these mean “meditation.” There is no deity-worship. The main principle is simply to sit with what is (Zazen). Before agreeing to ordination as a Zen monk/priest I had to be certain that the vows and practices I was taking on did not conflict with my Jewish values and beliefs.

This turned out to not be an issue with the American style of Zen Buddhism I was adopting. So, I guess I’m a JuBu or BuJu or Zen Juddhist!

Please talk about the Jizo-an Zen Community and your role in it.

As noted above, I joined the Zen Society over thirty years ago. I participated on-and –off with their meditations and teachings. I was invited to participate and teach there. The monastery moved to Cinnaminson, Shamong and currently it is known as the Jizo-an Zen Community in Cherry Hill. Under Roshi’s guidance I was able to expand my Awareness through a vigorous meditation practice. The Community is very eclectic and welcoming of those from different faith/spirituality practices. Roshi, other religious representatives, and I spoke at different local venues over the years, exploring the roles of religion and spirituality.

In 2016, Roshi asked me to be his personal assistant (Inji). In order to take on this role I had to be an ordained monk/priest. In 2017, I took the necessary vows and participated in the ceremonies that would ordain me as a monk/priest. Roshi chose the name “Chimon” for me. It means “Wisdom Gate.” Sadly, Roshi passed away in the Summer of 2021. But his Work continues on at the Jizo-an Zen Community. I currently serve on the Board of the Community, though I am not participating as much in meditations, teachings, etc.

You teach on the topic of the Kabbalah. Can you please offer a brief explanation of what it is and how we can incorporate the various aspects into our lives.

Kabbalah (“that which is received”) has become a general term for Jewish mysticism. There is disagreement as to when it began. Some believe it dates back to the Garden of Eden; others date it to the Middle Ages. It presents a way of looking at the Creation in an organized, stepwise manner. It also maps the human Soul and how it relates to God. It includes meditations and other spiritual practices to experience this relationship. Study of Torah and other texts from a mystical (Sod) perspective is key. While sometimes requiring an update based on science, equality, etc. it is still useful to many for spiritual growth. Kabbalah has been co-opted into non-Jewish forms, such as Christian Cabbalah and occult Qabbalah.

Please explain why you discourage people from being ‘searchers.’

All spiritual teachings contain stories of people that have undertaken serious, sometimes dangerous, journeys seeking “Something,” only to find that Something was with them all the time. So, the advice is not to seek, but to realize you are already There. Spiritual practice is usually necessary to find this out. It rarely happens spontaneously, though many claim that. It is called the Cosmic Joke: you are seeking that which you already are. It’s like trying to find your hands.

How are stories helpful teaching tools?

Stories appeal to a deeper part of the mind. It does this by disengaging the “rational” mind. When I would deliver a well-thought-out sermon and then ask my congregants what they learned, it is the stories (or jokes) they remember! I have studied many stories from Jewish, Sufi and Buddhist sources. And I have taught courses on storytelling.

Do you have a favorite to share that illustrates a knowing of God rather than a belief in God?

I say I don’t believe in God. “Believing” sounds too temporary and unsure: I believe in God today; I might not tomorrow. For as long as I can remember I have experienced God as Being, All Things. For me, this is the definition of a “mystic:” Someone who goes beyond study and belief and experiences the Divine. The Biblical Name for God means “Being.” Jokingly, I call myself an A-Atheist: one who does not believe in Atheists. If God is Being, then to disprove there’s a God you have to prove that you don’t exist!

What are the three ways you speak of to perceive God?

I learned this from Integral Philosophy and Martin Buber: Given the workings of the human brain, there are only three approaches to God.

I – I: acknowledging the God Within.

I – Thou: there is me and then there is God, out there somewhere.

I – It: All is God.

Of course, deific religions are I – Thou, worshipping or acknowledging a God apart from me, apart from the World, to whom I can pray. Other, usually non-deific forms of spirituality (like Zen or Jewish Kabbalah) tend to be I – I or I – It. Which is the best approach? They are all equal, and ideally, we should be able to experience all three realizations.

Who were/are your mentors and inspiration for the work you have been doing for the past several decades?

Draja Mickaharic — Inner Self Work, Wicca, Occultism

Rabbi Zalman Schachter – Shalomi — Kabbalah, Rabbinic studies

Idries Shah’s organization and books — Sufism

Dan Millman — Inner Self Work, general spirituality, numerology

Ken Wilber books — Integral Philosophy

Mark Nepo — spirituality

Stephen Seijaku Reichenbach, Roshi — Zen

Some very good psychotherapists!

How can readers reach you?

My email is rsimon31@gmail.com

I am not currently accepting students, nor do I read or reply to long emails. The Jizo-an Zen Community offers Zen teachings and meditations, in Cherry Hill, NJ, and on-line. Their site is www.jizo-an.org

Remember the Buddha’s final words: “ . . .rely on your own efforts.” Many blessings and prayers have been offered for your Awakening.

Edie Weinstein, MSW, LSW is a psychotherapist, colorfully creative journalist and author, dynamic speaker, and interfaith minister. She teaches people how to live rich, full, juicy lives. Find her at www.opti-mystical.com