The higher the mental development of a woman, the less possible it is for her to meet a congenial male who will see in her, not only sex, but also the human being, the friend, the comrade and strong individuality, who cannot and ought not lose a single trait of her character.

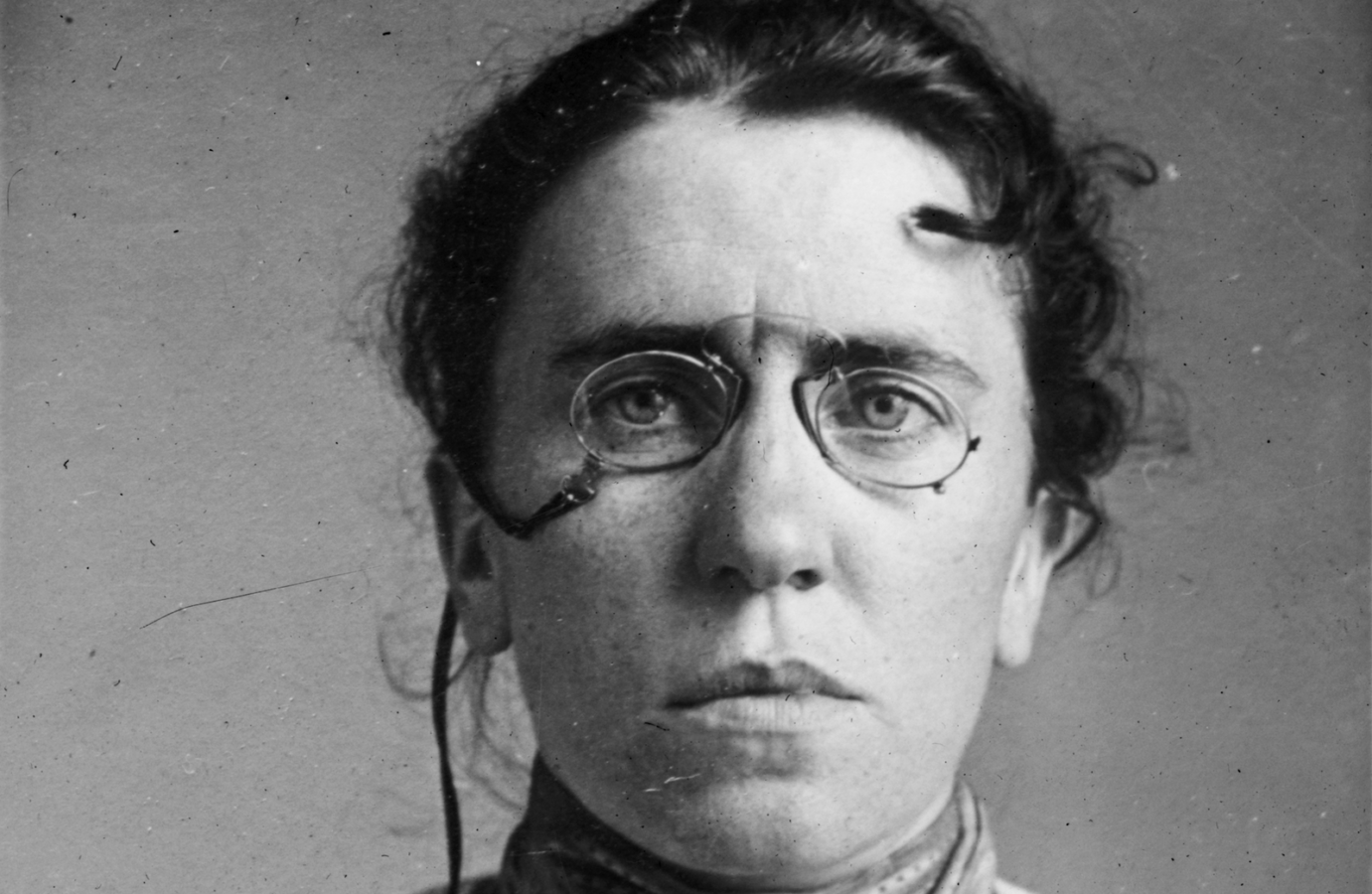

A party in New York, just before the turn of the century. A young Jewish woman from Russian Lithuania is there, a remarkable person who ran away from home at the age of 16 to escape a forced marriage and made her way to the US. There are many other young radicals and intellectuals present, including others who are, like her, anarchists. She is bespectacled and bohemian looking, with a strong, yet somewhat pixie-ish face and long curly hair held up in a bun. One might say she looked somewhat like a pirate. As the band kicks up a joyous dance number, she joins with abandon. Her happy dancing attracts the attention of a taciturn radical who tells her with a frown “that it did not behoove an agitator to dance. Certainly not with such reckless abandon, anyway.”

Goldman responded furiously: “If I can’t dance, then I don’t want to be part of your revolution.”

Well, or at least she said something like that. Later, in her 1931 autobiography, Living My Life, she said, “I told him to mind his own business, I was tired of having the Cause constantly thrown in my face. I did not believe that a Cause which stood for a beautiful ideal, for anarchism, for release and freedom from conventions and prejudice, should demand denial of life and joy. I insisted that our Cause could not expect me to behave as a nun and that the movement should not be turned into a cloister. If it meant that, I did not want it. I want freedom, the right to self-expression, everybody’s right to beautiful, radiant things.” This telling of the episode was later paraphrased by others in the pithy quote above.

Emma Goldman was born in 1869,in Kovno, Lithuania, then part of the Russian Empire. By that time radical political movements were well underway in Europe, which would soon go to war against the status quo throughout the West and then the East. The intellectuals of the day fiercely debated solutions to the brutal systemic injustices which plague the world, taking sides in a plethora of different ideologies of thought and action. The Jewish youth were impassioned by these ideas; Jewish participation in socialism and communism were so widespread that Jews and communism came to be united in the popular imagination for decades to come.

Goldman, born into a religious family, ran away when her father tried to force her into a marriage she didn’t want. She would literally never stop running from the chains people wanted to catch her in, though along the way she would dedicate her life principally, not to her own freedom, but the freedom of others. By the age of 21, she was a dedicated anarchist and a fiery speaker on a lecture tour, using powers of rhetoric which are still admired a century later.

The demand for equal rights in every vocation of life is just and fair; but, after all, the most vital right is the right to love and be loved.

In the US, Goldman fell in love with the Anarchist activist Alexander Berkman, who would soon be convicted of the attempted assassination of the industrialist Henry Clay Frick, in retaliation for the killing of nine striking steelworkers by Pinkerton detectives ( a private security force allied to political and business powers). Goldman was never charged, but for the rest of her life she was harassed by police. Jailed many times, in 1893 she served a year for incitement to riot; she was jailed again in the aftermath of President McKinley’s assassination by an anarchist, imprisoned again for disseminating “obscene” birth control literature in 1916, then again in 1917 for organizing against forced military conscription.

Anarchism, then, really stands for the liberation of the human mind from the dominion of religion; the liberation of the human body from the dominion of property; liberation from the shackles and restraint of government. Anarchism stands for a social order based on the free grouping of individuals for the purpose of producing real social wealth; an order that will guarantee to every human being free access to the earth and full enjoyment of the necessities of life, according to individual desires, tastes, and inclinations.

For Goldman, anarchism was a protest against unjust hierarchy, oppression, state violence, prejudice, and irrational convention. Her commitment to a human dignity that pre-existed any state or any state-given rights could sometimes lead her into controversial statements, as in her famous quip, “Ask for work. If they don’t give you work, ask for bread. If they do not give you work or bread, then take bread.”

In 1919, Goldman was deported back to Russia, where she quickly spotted the totalitarian tendencies of the Bolsheviks and became an early critic. Her experiences in Russia led her to change her belief that the means might sometimes be justified by the ends, one of several changes in her always evolving thought. In the afterword to My Disillusionment in Russia, she wrote: “There is no greater fallacy than the belief that aims and purposes are one thing, while methods and tactics are another….” Goldman came to be wary of the use of political violence, although she continued to sympathize with the use of it by those oppressed by dominator hierarchies.

Goldman was an early, and fierce, feminist. In 1897, she wrote:

“I demand the independence of woman, her right to support herself; to live for herself; to love whomever she pleases, or as many as she pleases. I demand freedom for both sexes, freedom of action, freedom in love and freedom in motherhood.”

Goldman was also an outspoken critic of discrimination and hatred against homosexuals. Her belief that social and legal liberation should include gay men and lesbians was virtually unheard of at the time, even among anarchists. As German-Jewish sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, who is often viewed as the father of LGBTQ rights, wrote, “she was the first and only woman, indeed the first and only American, to take up the defense of homosexual love before the general public.”

In numerous speeches and letters, she defended the rights of gay men and lesbians. “It is a tragedy, I feel, that people of a different sexual type are caught in a world which shows so little understanding for homosexuals and is so crassly indifferent to the various gradations and variations of gender and their great significance in life,” she wrote.

Goldman’s defense of the rights of women, workers, LGBTQ people, and the poor; her defense of free speech and free thought, and her opposition to capitalism, human rights abuses, and warfare make her a great prototype of the intersectional activist. Her life is also, however, a lesson about what are most likely inescapable limits to intersectionality; although Goldman spoke out against racism, she did not give it nearly as much attention as other issues, whether that reflects a feeling on her part that her opposition to racial hierarchies was implicit in everything she said (which I suspect) or arose from a lack of an acute personal attunement to the issue (which may also have been a factor). Although an intersectionality reflected in an equal commitment to all issues of justice remains a worthy ideal, it is unlikely one human being can perfectly attain it.

In her independence of thought, uncompromising honesty and bold, self-endangering action, Goldman has few peers in history. In 1936, after living in Germany, England, France and Canada Goldman went to Spain to enlist with the Loyalists against the Fascists. When Franco’s Fascists won, Goldman returned to Canada, from where she raised money for the victims of the war. She died in Toronto, Canada, on May 14, 1940.

I’d rather have roses on my table than diamonds on my neck.

Matthew Gindin is a journalist, educator and meditation instructor located in Vancouver, BC. He is the Pacific Correspondent for the Canadian Jewish News, writes regularly for the Forward and the Jewish Independent and has been published in Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Religion Dispatches, Kveller, Situate Magazine, and elsewhere. He writes on Medium from time to time.