Elisha Waldman has the credentials of a doctor: the degrees, the training, the experience. His hospital ID badge reads that way as well: physician.

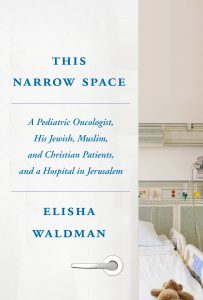

Don’t be fooled by those labels, for, at least from my impression, Waldman actually functions as clergy with the outward trappings of a doctor. I gained this notion from reading his recent memoir, This Narrow Space, and speaking to him in a a phone interview. In fact, the pediatric oncologist and palliative care specialist has long experience with watching clergy, as he grew up in a rabbinic family. I imagine that, for families Dr. Waldman works with, in many ways, he functions much as his father, Rabbi Leon Waldman(Jewish Theological Seminary Rabbinical school class of 1972), must have during his time in the pulpit in Fairfield, CT.

Waldman comes into contact with families at a harrowing juncture, when a child is critically ill. To help the families he works with, Waldman cares about words and how he speaks to patients. He also cares about hope, however that illusory concept may be defined. The doctor writes of hope, “I learn that hope- and hoping- is a far richer concept than I had suspected. I’ve learned to treat hope not as a noun but as a verb. Hope as a thing, as an object, can be shattered or lost. But hoping as an act doesn’t really ever have to stop.”

This sounds as good as anything most of us hear coming from the pulpit. After all, a rabbi, in many ways, attempts to give shape to the events of the world, whether it be current events in a weekly Sabbath sermon, or allowing the assembled to understand how to frame and process the enormity of the moment at a life cycle event. Waldman spent seven years at Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem and, in his time there, treated patients and their families from every sector of Israeli society – cancer seems to be undiscriminating in its ability to target all families.

He writes about how “a fair amount of literature has emerged over the past few years suggesting that spiritual care should in fact be a routine part of medical care-certainly when dealing with patients facing potentially life-threatening illness.” Waldman’s job as a pediatric oncologist, and especially later when he trains as a palliative care specialist, is both to help families choose how to treat illness and to aid them in finding ways to cope. In fact, Waldman told me in a phone interview that “at the heart of palliative care is the creation of the narrative.”

In our phone conversation on an afternoon he had off from seeing patients, he spoke about the value of words to those in palliative care. He told me that “in palliative care we have a saying, ‘our conversations are our procedures and our words are like scalpels.'” He wasn’t sure who to attribute this to, but added that most medical professionals do not have “a deep enough respect for what words can do, both good and bad.”

Waldman emphasized this, as I had quoted to him something that he wrote in an email to the mother of one of his patients, Jacqueline Dooley, which she used in an essay she wrote in Longreads, about parenting a child who is no longer living. Dooley was concerned that she not give her child false hope and Waldman replied to her, “One of the most wonderful and amazing attributes of the human soul is the near impossibility of crushing all hope. This is a gift. I don’t know if it’s God, or nature, or evolution, nor do I care — it is a beautiful and vital part of what makes us human. We have actual published data that people (patients and parents alike) can (and want to) hear frank, stark information about their prognosis, are able to internalize the fact that they are going to die of their disease, and yet still simultaneously maintain some sort of hope. The ability to simultaneously grasp one’s own mortality while still hoping for something is one of the beautiful paradoxes that makes us human and that allows us to function.”

Waldman emphasized this, as I had quoted to him something that he wrote in an email to the mother of one of his patients, Jacqueline Dooley, which she used in an essay she wrote in Longreads, about parenting a child who is no longer living. Dooley was concerned that she not give her child false hope and Waldman replied to her, “One of the most wonderful and amazing attributes of the human soul is the near impossibility of crushing all hope. This is a gift. I don’t know if it’s God, or nature, or evolution, nor do I care — it is a beautiful and vital part of what makes us human. We have actual published data that people (patients and parents alike) can (and want to) hear frank, stark information about their prognosis, are able to internalize the fact that they are going to die of their disease, and yet still simultaneously maintain some sort of hope. The ability to simultaneously grasp one’s own mortality while still hoping for something is one of the beautiful paradoxes that makes us human and that allows us to function.”

It is clear that he is a physician concerned with the soul and the spirit, not merely the body. For Waldman, this need to hold on to hope, though it may need to be redefined as the patient’s conditions change, is something he helps both patients and their families work through.

In This Narrow Space, Waldman writes of being called up to reserve duty in the Israeli army during the 2014 war in Gaza and, when he returns, being asked by the family of an Arab patient where he had been. Waldman writes, “I had been so proud of what I’d been doing, even enjoying the training and looking forward to my first deployment in the reserves, so I am annoyed with myself when I feel my face flush with embarrassment. The women’s faces fall for an instant. But then, barely missing a beat, one of them looks up at me, manages a small smile and says, ‘We wish there were more people like you in the army. Maybe things would be different then.'”

Waldman faces the situation of ambiguity constantly, wanting to care for all his patients equally, but having the larger forces of the world outside the oncology ward make them at odds, though inside they are all fighting the battle against cancer. How to care for patients when outside the hospital there is a war going on?

One of the most interesting aspects of This Narrow Space is the opening it gives readers onto the various groups that make up Israeli society. When writing, he told me by phone, he conceived of the book as a work about Israel. Waldman meets Jews and Arabs from all segments of the country and becomes part of their lives in an incredibly intimate way. Part of the need for him as a physician to understand the family comes from their religious views, some of which he finds hard to understand. There were families who said they would rather have a child dead than amputate a leg, those who are in denial about the nearness that the patient is to death, and those who consult a rabbi who is in touch with all manner of medical specialists and recommends specific doctors to his flock.

The book educates, as well, about how the medical mind works. I, and I think most non-medical professionals, assume physicians are trained to make decisions on what the best courses of action to heal a patient are, and to know how to treat an illness… that their job gives them the unassailable credentials to decide precisely what to do. However, Waldman is not afraid to let readers know that much of what doctors think they know is not a certitude, that medical professionals dwell in a land of probabilities and percentages, and don’t actually ever know precisely how an individual patient will respond to a particular treatment protocol.

Waldman writes, “Now I see things in a much less binary way. Patient care is not an either/or construct, cure-driven or comfort-driven. Decisions and goals can be, and usually are, much more nuanced.” This is startling, coming from someone whose profession has often been seen as peddling certainty to its customers.

Waldman speaks of his training in palliative care as helping him “become more at ease with ambiguity. This is evident as I become more comfortable accompanying my patients into the gray areas of prognostic uncertainty. But it’s also evident in my own life. Process theology, which somehow accepts a divine force that is all-powerful and all good, yet also paradoxically, limited somehow jibes with my own experience… In keeping with the principles of palliative care, I’m learning to embrace uncertainty as simply a part of living.”

In our interview, he says as well that writing helped clarify things in his life. In fact, after he published the essay “Double Exposure” that eventually shifted into the book in spring 2014, he met the woman who became his wife. He said that “it is not an accident that I only settled down and married after palliative care training.” Waldman explained that “wallowing in the grayness with these families, the lessons from all of that I bring home and learned have allowed me to settle down.” In the time between when he wrote the first essay and the present, Waldman married and, in the past month, has just become a father to a second son.

He writes about the first time he was with a patient as she died and the first time he was asked to help clean the patient’s body after death. He explains that “tubes, IVs, catheters, and tape” are removed, and wounds are sewn up. Waldman hesitated when the nurse asked whether he wanted to assist. But he writes, “What surprised me most was that the process was also transformative for me. I felt a sense of fulfillment of my responsibility to this person who had been entrusted into my care.”

Now that he has a family, not just patients entrusted to his care, readers will have to look forward to hearing about the doctor’s next experiences.

Photo Credit: Michael Lionstar

Beth Kissileff is the co-editor of the anthology Bound in the Bond of Life: Pittsburgh Writers Reflect on the Tree of Life Tragedy, author of the novel Questioning Return and the editor of the anthology Reading Genesis. Her writing has appeared in the Atlantic, Michigan Quarterly Review, New York Times, Tablet, the Forward, 929English and Haaretz, among others. Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.