In 1986, I went on a journey to Atlanta to return home. No, I do not come from Atlanta or anywhere in the South. I grew up in Los Angeles as a secular Jew. Later, I moved to Oregon and became a professional storyteller, telling world folktales. I was ready to return home to my roots in Judaism by telling Jewish stories, the stories of my people.

When I called the number listed for a Jewish storytelling festival in Atlanta, Peninnah Schram, who I would later learn was the Grande Dame of Jewish Storytelling, answered. She told me, without hesitation, “You must come.”

At the conference, Peninnah and other tellers welcomed me as I soaked up the Jewish folklore. I heard tales that had sifted down through generations: stories of wise rabbis, clever peasants, benevolent kings, and bumbling schlemiels. I was enthralled and determined to add them to my repertoire.

As a secular storyteller, I specialized in stories with powerful female protagonists and I fully expected to find some prime examples of their presence in Jewish stories. After all, Jewish women are famously strong. But I was surprised to find that in all of the hundreds of anthologies of Jewish stories, only two featured women.

I have to admit that it was so satisfying to be telling the stories of my people, rather than Chinese or British fairytales, that at first, the lack of female characters hardly bothered me. It was thrilling to be transmitting the lessons of Torah, of compassion and atonement, mixed with wry humor, all found in these profound tales. I felt deeply at home in the world of Jewish storytelling.

Somewhere along the way, I began to slip some female characters into the Jewish stories I told. My criterion was simple, albeit unconscious: If the gender change did not alter the plot or the meaning of the tale, it seemed kosher. My audiences enjoyed the tellings, and the alterations felt more aligned with my values.

Meanwhile, other aspects of Judaism were catching up with feminism, big time. Women were being ordained as rabbis in increasing numbers. Feminist interpretations of the Torah were becoming commonplace. Everything was evolving… except the stories. Even though I assumed other Jewish women storytellers must be altering genders of characters in their oral renditions, no one had dared commit those alterations to anything official, certainly not to print.

In 1995, my husband, David, was ordained as a rabbi and I was ordained as a maggidah (female Jewish storyteller / preacher) by Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, the founder of the Jewish Renewal movement. The two of us began our first maggid training program in 2009. I taught the storytelling portion and David led the Torah learning; it was a natural collaboration. Our first cohort, in Portland, Oregon, turned out seven fine maggidot. Four more cohorts of maggid students followed, all of which had more women than men.

While training students, my own style continued evolving, which meant altering the gender of characters and blending traditional with personal stories. A mute boy who plays the flute in a traditional Bal Shem Tov story became a wild, unruly girl, a vilde chaya, who was ostracized, and then went on to lift the congregants’ prayers to heaven with lyrical, melodious notes from her flute.

At the same time, I encouraged my maggid trainees to adapt material to create their own styles of storytelling. They developed personal stories and experimented with original stories, which often had a feminist perspective. Two of our students created a Torah dialogue that told the Passover story from the point of view of the midwives, complete with loud grunts of women in childbirth.

I recorded many of my original and blended stories on a CD in 2005, but still hesitated to put them in writing. Although I knew the only reason women were missing from Jewish stories was that they’d been written down by men, I was hesitant to be the lone woman who wrote down alterations to the sacred folklore.

A couple of things happened during the pandemic that ultimately boosted my courage to make changes. First, I was working online with my eleven-year-old granddaughter, teaching her to tell stories. I asked her to visualize characters in her story, an essential tool for storytelling. When a teller imagines the characters, she can identify with them, and more clearly convey images to listeners. That helps the audience relate to the story, and fully absorb its message.

I guided my granddaughter on a visualization of Elijah the prophet, a well-known wisdom character in her story, and asked her to describe what she saw in detail. She said immediately, “I see a woman.” It was as if something shook loose in my mind that couldn’t be put back. My granddaughter had innocently found a way to put herself into the world of the story, and I felt a new urgency to help women see their own images in our wisdom tales.

Around the same time, our maggid students were studying stories of the Baal Shem Tov (the famous, holy rabbi who founded Hasidism). One of the students declared, “These stories are not only all male, but some of them are downright sexist,” and we all had to agree. After that cohort graduated, I asked the newly-ordained maggidot if they’d like to collaborate on a new anthology of stories, one that put women in the leading roles. The consensus was a unanimous “yes.” The concept of Tikkun Olam, meaning to repair the world, is an omnipresent goal in Judaism, and this would be our contribution to fixing something that had gone so wrong. The role models that had been missing for half our audiences were going to be coaxed back into existence.

Thus began a three-year collaborative journey of women who dove into the process of feminizing our sacred stories, adding our original and personal tales, and bravely submitting the work to be published. We needed to ask permission from the major forces in Jewish storytelling, to get their approval to alter renditions of their tales. I mentally cringed, expecting a rebuke, each time I sent a request for permission. But when all of them—Peninnah Schram, Howard Schwartz, and others—were surprisingly enthusiastic, I knew we were riding a tidal wave of transformation whose time had come.

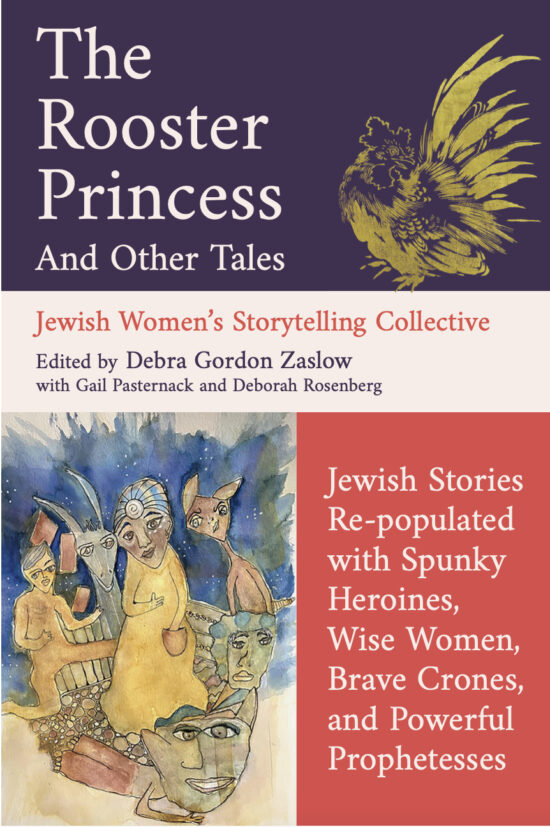

With the publication of our anthology, The Rooster Princess and Other Tales: Jewish Stories Repopulated with Spunky Heroines, Wise Women, Brave Crones, and Powerful Prophetesses, it seems we have nudged Judaism one step further into a modern era that still holds our sacred traditions, but is egalitarian. Just like progressive prayerbooks have added Imahot (the Mothers) to the Avot (Fathers) in the Amidah, now the adventurous character of Avram in the “Treasure Under the Bridge” is a woman named Chana. Simple, but profound.

I see now that attending the Jewish Storytelling conference in 1986 was not exactly a return to my Jewish roots; rather it was a first step on the road home. The longer journey turned out to be joining with other women to make it a home in which we can thrive: a world of inclusive Jewish stories.