I remember him standing at the head of the table, wearing a fur hat and light gold gown, holding a beautiful kiddush cup.

No, not Philip Roth, obviously. I was in Israel for the first time and found myself in a group being led from the Western Wall to the black hat neighborhood of Meah Shearim for Friday night home hospitality. Each of us were brought to a different home to experience what was touted as the real deal: A chassidic family celebrating Shabbat, Shabbos, in all its beauty and piety. There was, in addition to the fragrances of the delicious and hearty meal to come, a smell that later I would identify as boiling wine. The wine was being boiled because of a strict understanding of a Jewish law that in order to remain Kosher, untreated wine had to be handled only by Shabbat observant Jews. Something I was not at the time, nor in all likelihood would be seen as in this household, even now.

At that table in Meah Shearim were my host in full regalia of his chassidic sect and a good number of children, all boys. And standing through a door to a small kitchen were the women and girls. The Torah portion for that week, as it was this week, was Naso and my host began his thoughts about the story of the Sotah, the married woman suspected of having sex with a man other than her husband who is brought to the Tent of Meeting and given a kind of trial by ordeal. She must drink water made bitter through the dust on the Tabernacle floor and, according to the Rabbinic tradition, into which has been dissolved a copy of the Divine Name. If she shows no ill effects, her name is cleared. If she does, she is held guilty and put to death. So, not exactly a fair trial and pretty much the embodiment of antipathy toward woman’s sexuality, independence and volition.

And this was my host’s point: the Sotah ritual was not only to teach us of the necessity of aligning the will and obedience of wives with husbands, but, by extension, the necessity of each Israelite to align with G*d. That there should be, as he put it, one ratzon, one will, the Divine will to which all must be obedient and never, like the Sotah, go astray.

That Shabbat meal, marked by its attempt to achieve a kind of perfect piety at the expense of inclusion and the enforcement of the univocity of the ideal world made its impression. The words of Torah shared that day did me a great service by tracing out the very opposite of how I saw the world and providing a reverse moral compass for finding meaning in the same passages.

For me, the Sotah is a different kind of cautionary tale, pointed to not so much the Biblical account, as an engagement with the context. Before and after this passage, there are more inclusive legal cases, each introduced by the words ish o isha, “If a man or woman”. The Sotah not only has no place for isha, woman, but actually says ish, ish.”a man, a man” as if to cement the idea that there is only one perspective given. For me, rather than an ideal to be replicated up the ladder to G*d, the Sotah was a proof for why it is a fool’s errand to try to know, let alone appropriate, the Divine will, and a great danger to mute another’s voice or experience in favor of one’s own.

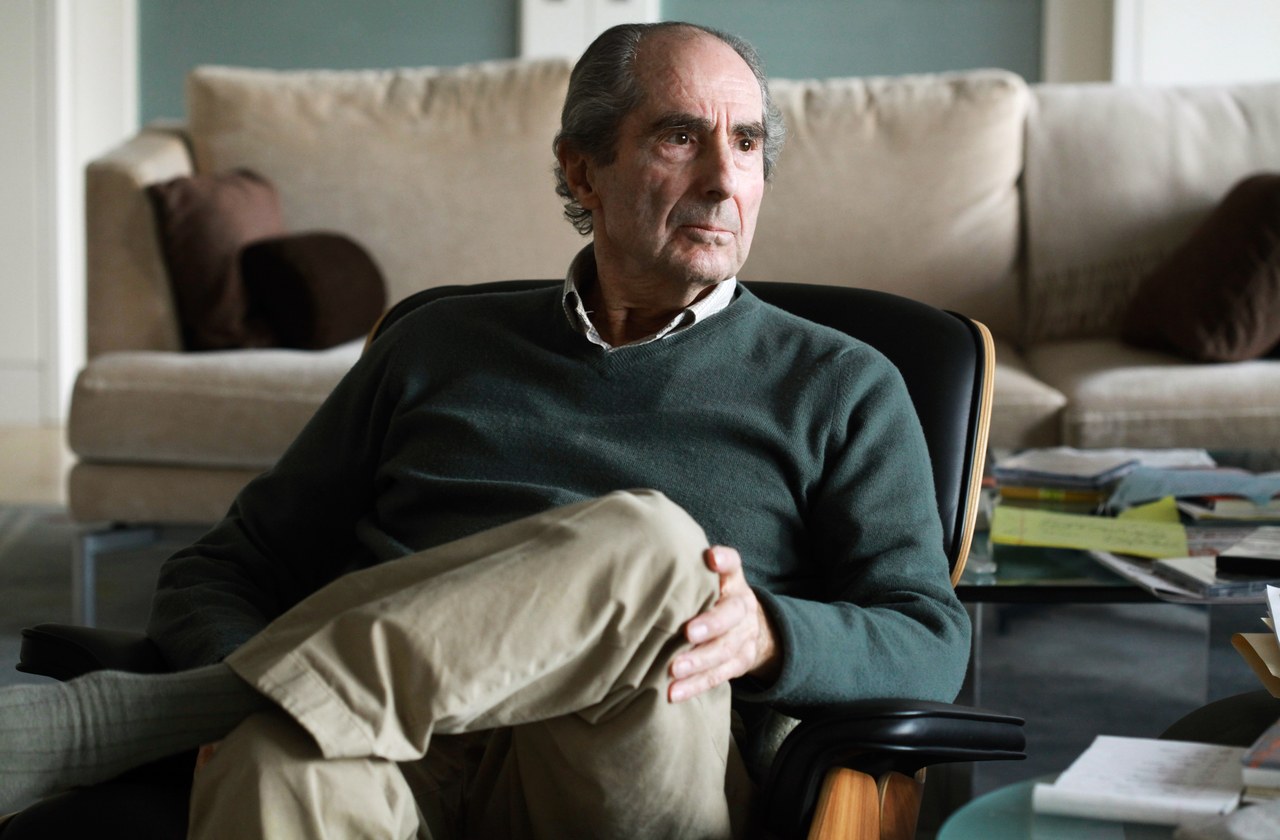

These passages from the portion Naso, are read this week that saw the passing of Philip Roth and renewed the conversations about his significance as the chronicler of a particular slice of post-war American Jewish life and explorer of the depths of his own experience. Roth, of course, wrote a world in which such obedience to the Divine is far from the scene, along with outward and inward trappings of piety and restrictions on sexuality. And yet, in thinking of both Roth and the chassidic man, I am led to feel that they have more in common than I do with either of them.

The monolithic approach to the world may be more obvious in the restrictions of Meah Shearim (although by no means can such a broad brush be applied to the actual residents of this or any other neighborhood.) However, they have their analogue in the counterlife often depicted by Philip Roth.

Because neither Roth nor my host, who might have been called unironically a fanatic (though his dress was much fancier than the shlumpy suit that both mortified and attracted Roth’s own Eli the Fanatic), believed in discovering a perspective other than his own.

Roth was known for mastery, just as much as he was for masturbation. He was the master of post-war American fiction. The master of the art of the sentence. The master of the discourse of secular, assimilated Jewish life. Of a world without a god or a life of the spirit. And, most of all, a master of his own life, a master of his own domain, so to speak.

Roth’s description of the act of writing as a revelation that comes to him through his own language makes even clearer his deep investment in his own mastery. He was not moved by the idea that there might be more on heaven and earth than is dreamt of in his philosophy, whether as expressed in others or in some mystery of the universe.

Roth was, to borrow a line of thought from the writer Dara Horn, much less curious to explore other’s experience than to depict characters that fleshed out his own interior investigations… who populated the worlds of his various protagonists who were almost all built of similar, in some cases identical, elements of his own roots.

This lack of curiosity certainly affected his portrayal of women, mothers or lovers, Jewish or otherwise. And the debate over whether this limitation stems from or should be labeled as misogyny is a vital and necessary one about his work. Less interesting to me is the ever-present question of whether Roth’s window on Jewishness constituted or reflected anti-Semitism, or just an unsentimental description of Jews. In any case, he relied only on his own powers of observation and rationality. What he called “no taste for delusion” also gave him no interest in exploring beyond the bounds of his own perspective.

And in that, he was, without the fur hat and the gold bekishe, a believer in one ratzon. One will. Not G*d’s will, but his own. To master the world of meaning around him, channel his own significant genius, and leave no possibility to be interrupted by another unknowable mind. To imagine, engage, and inscribe the experience, but not to be transformed by another and their world.

The writing of Philip Roth is a revelation, at times deeply affecting, beautiful, and meaningful, but also uncompromising waters that bring all who drink them in line with one master. I can draw enjoyment and provocation from his work, but his Torah only inspires me to look to others.

Michael Bernstein, a Rabbi, has served since 2009 as Rabbi of Congregation Gesher L’Torah, a vibrant and dynamic Synagogue community in north Atlanta where each person’s story is embraced and Judaism is personal. He was ordained as a conservative Rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York in 1999. He and his wife Tracie have three children, Ayelet, Yaron and Liana.