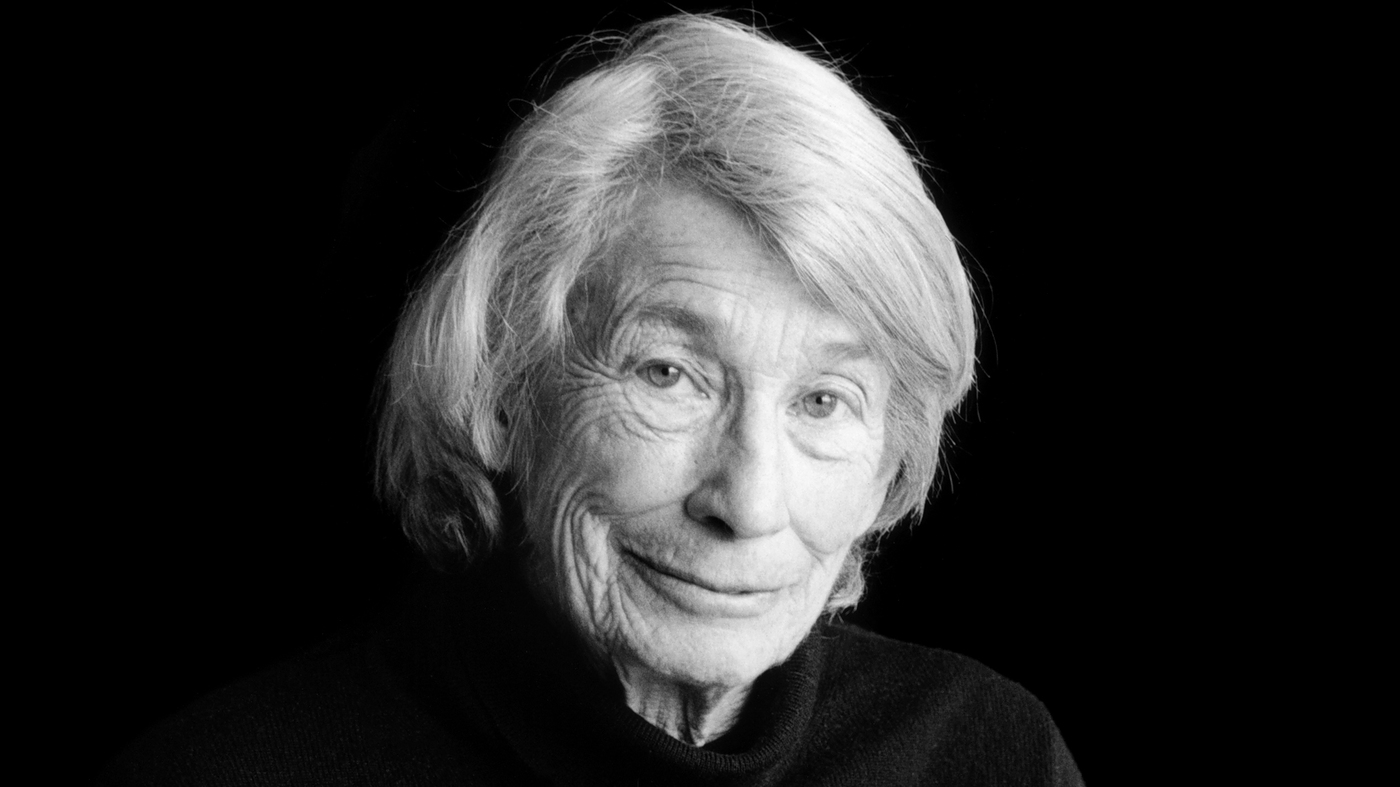

The poet Mary Oliver is a different kind of dissident. Most people would not view her as political, and blurbs about her online don’t use the words “activist” or commonly apply any other “ist” to her description. No one would call her a radical, and she is unlikely to have a dossier with the FBI.

Yet Oliver’s quiet voice has been preaching a gentle overturning of the world for decades, calmly speaking in her playful, dignified, plaintive, and occasionally mildly indignant cadence.

Her poems are, more than anything, about personal renewal- the rebirth of the soul through a self-giving to quiet attention, to unfettered nature, to companionship with living things, love of the other (the “neighbor” of Biblical parlance) and a grateful and gentle reckoning with life in all of its dark and light.

I thought the earth remembered me,

she took me back so tenderly,

arranging her dark skirts, her pockets

full of lichens and seeds.

I slept as never before, a stone on the river bed,

nothing between me and the white fire of the stars

but my thoughts, and they floated light as moths

among the branches of the perfect trees.

All night I heard the small kingdoms

breathing around me, the insects,

and the birds who do their work in the darkness.

All night I rose and fell, as if in water,

grappling with a luminous doom. By morning

I had vanished at least a dozen times

into something better.

–“Sleeping In The Forest” (Sleeping in The Forest, 1978)

Oliver’s poems do many of the things others do- explore death, embody the beauty of the natural world, place themselves in the intimate, painful, or erotic spaces where love plays out- but those things are not what is distinctive in her work. Oliver is a poet of gratitude in an age of entitlement; a poet of praise in an age of criticism; a celebrant of the unstructured, the free, the un-guilty, in a time dominated by clocks, speed, and a paradoxical embrace of both the brash and the puritanical. That is what makes her a dissident.

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean-

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down-

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

“The Summer Day”, (New and Selected Poems, 1982)

Oliver’s poems, as should be apparent, are dominated by the natural world, which in her vision is full, not of objects, but of actors. As Debra Dean Murphy, a student of Oliver’s poetry for many years, wrote of Oliver’s work in Christian Century, Oliver “works from the ‘grammar of animacy’–plant ecologist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s term for linguistic patterns and structures that communicate the moral inclusion of all created matter into human speech, naming the world as ‘a neighborhood of nonhuman residents.'”

To quote Murphy’s compilation of examples, Oliver “writes of goldfinches ‘having a melodious argument’; frogs ‘shouting / their desire, / their satisfaction’; the moth that ‘has trim, / and feistiness’; the earth which ‘took me back so tenderly, arranging / her dark skirts, her pockets’; a turtle ‘filled / with an old blind wish’; and trees that ‘give off such hints of gladness.'”

Oliver has also been credited with writing poems that save lives, most famously her “Wild Geese”:

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

For a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about your despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

-Dream Work, 1986.

Oliver’s work is not without its dark journeys as well, grappling with, among other things poverty, loss, injustice, heartbreak, and the mystery of evil, albeit always in her own distinctive way which situates these things within the gratuitous, ungraspable beauty of the world. Most famous is her grappling with her father’s sexual abuse of her as a child, most pointedly in the masterful and harrowing “Rage”:

You are the dark song

of the morning;

serious and slow,

you shave, you dress,

you descend the stairs in your public clothes

and drive away, you become

the wise and powerful one

who makes all the days

possible in the world.

But you were also the red song

in the night,

stumbling through the house

to the child’s bed,

to the damp rose of her body,

leaving your bitter taste.

And forever those nights snarl

the delicate machinery of the days.

When the child’s mother smiles

you see on her cheekbones

a truth you will never confess;

and you see how the child grows —

timidly, crouching in corners.

Sometimes in the wide night

you hear the most mournful cry,

a ravished and terrible moment.

In your dreams she’s a tree

that will never come to leaf —

in your dreams she’s a watch

you dropped on the dark stones

till no one could gather the fragments —

in your dreams you have sullied and murdered,

and dreams do not lie.

(Dream Works, 1986)

Then there is the almost unbearingly moving “Poem for my Father’s Ghost” which she wrote for him after his death, a poem whose shattering generosity can produce nothing but a kind of stunned reverence:

Now is my father

A traveler, like all the bold men

He talked of, endlessly

And with boundless admiration,

Over the supper table,

Or gazing up from his white pillow —

Book on his lap always, until

Even that grew too heavy to hold.

Now is my father free of all binding fevers

Now is my father

Travelling where there is no road

Finally, he could not lift a hand

To cover his eyes.

Now he climbs to the eye of the river,

He strides through the Dakotas,

He disappears into the mountains, And though he looks

Cold and hungry as any man

At the end of a questing season,

He is one of them now:

He cannot be stopped.

Now is my father

Walking the wind,

Sniffing the deep Pacific

That begins at the end of the world.

Vanished from us utterly,

Now is my father circling the deepest forest —

Then turning in to the last red campfire burning

In the final hills,

Where chieftains, warriors and heroes

Rise and make him welcome,

Recognizing, under the shambles of his body,

A brother who has walked his thousand miles.

I have to admit that I don’t like every poem Oliver has written, and there are days and times when I’m as likely to toss one of her books away in irritation than to read it. Amidst the hectic battle of life in the everyday capitalist maelstrom, with the shadows of international conflict and ecological degradation darkening the landscape more and more, Oliver’s gently preaching, teasing, and reverential voice can sometimes grate. I think, though, this is more of a fault in me than in her. At such moments I try to slow down, breathe, and read again what she is saying with a less jaundiced eye. This doesn’t always work- sometimes I still find something that strikes me as a little too easy or light, especially in her later poetry, but most of the time I find myself finding her both true and worth listening to.

Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention.

Be astonished.

Tell about it.

– “Sometime” (Red Bird, 2008)

Matthew Gindin is a journalist, educator and meditation instructor located in Vancouver, BC. He is the Pacific Correspondent for the Canadian Jewish News, writes regularly for the Forward and the Jewish Independent and has been published in Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Religion Dispatches, Kveller, Situate Magazine, and elsewhere. He writes on Medium from time to time.