Imagine a young couple, happy and bubbling with anticipation over the birth of their first child. Only a few months are left before the big day.?But then, a sonogram reveals an anomaly – maybe in the shape of the skull, or the size of the kidneys. Something isn’t?quite right.

Hearing such news is among the most devastating things a parent can experience. Thrown into panic mode, parents hunger for more information, and grasp for something tangible to help them understand what is happening with their child. Will my baby be OK? Will she be healthy? Will he be normal? What kind of life will she have? How will we all function? It’s a situation that cries out for a diagnosis. It demands to be named.

The ability to see more allows us to find more patterns and meaning, so we confront – and potentially even change – the human condition.

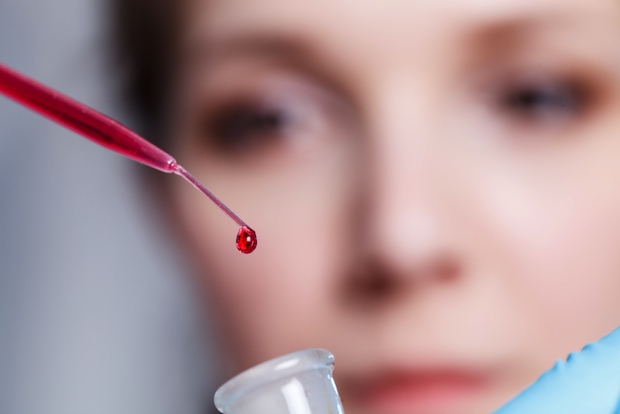

Sara Huston Katsanis, an instructor with Duke University’s bioethics initiative, Science and Society, works with families who find themselves in these extremely trying circumstances. She uses the new technique of whole genome sequencing of the child and parents in order to examine their billions of pieces of genetic code.

The goal in sorting though this tremendous amount of genetic information is to find clues – places here or there which might point to the source of the anomaly. Knowledge can give us some sense of control, especially when we feel totally overwhelmed. It gives us power to assuage the tempest inside.

So if knowledge is power, then more knowledge would lead to more power. And that’s where Big Data comes in. Through Big Data, one can see how evolution creates, molds and destroys; such processes can be seen in individuals, in groups and in all of humanity over time.

Dr. Greg Samsa is a biostatistician at the Duke University School of Medicine who likes Big Data. He takes billions of pieces of genetic information from studies (such as Dr. Katsanis’ work), then reaches deep down inside and tries to pull out its meaning. He says in this interview that genomics gives him and his peers a good perspective on how evolution works: “It’s utterly remarkable once one does simulations [and] looks at the play of chance, how profound the changes are in populations.”

Beyond seeking the small clues that may diagnose rare conditions in individuals, Dr. Samsa can look for patterns across many people to discern a view of life that most can’t possibly imagine. Whether it’s one person’s genetic code or the age of the universe, Big Data creates billions and billions of pieces of information, forcing us to think about numbers we don’t live with on a day-to-day basis. And once we’re able to make sense of the data, we begin to see where we’ve come from, how we came to be, and perhaps, what’s keeping us from becoming who we want to be.

While the ability to see more allows us to find more patterns, make more meaning and assign more names so we confront – and potentially even change – the human condition, it also leaves us with several questions.

- Are we nearing a time when technology can tell us all (or most) of what we need to know?

- If so, do we let big corporations and institutions lead the way, with the regulatory agencies following behind slowly?

- Even more importantly, where do questions of purpose – right and wrong – come in? In other words, what happens when we are able to change our genes?

- If knowledge is power, then how should we use this power?