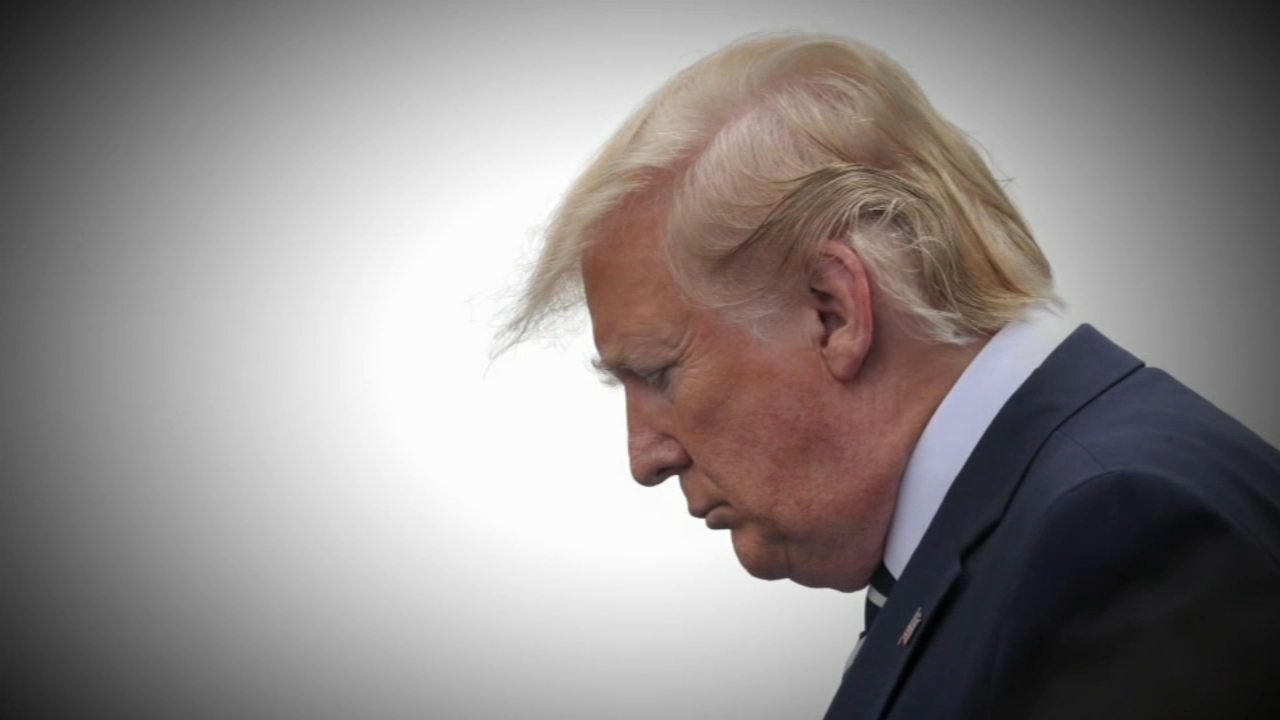

Through all his folly, what makes Trump a worthy object of reflection is his astuteness in understanding an all too common single-sided psychology of leadership and power: He knows that yelling over someone can make you look powerful even if you’re full of baloney; that to many, a facade of wealth is more important than generosity; and that we often read sickness as a sign of weakness — Trump-style tyrants don’t get sick. Well everyone gets sick, they go through theirs in hiding.

Trump’s veneration of this single-sided vision of power is supported by thousands of years of mythology. In many ways, gods and leaders fill the same psychological function, they are ubermenschen, visions of what we can aspire to (or become). And the gods through all the literature of humankind have been warriors, poets, healers, rain-makers, crop-growers, creators, sex-abusers, death bringers, and so forth. Where though are the gods of sickness? Where are the gods bed-stricken with weakness and fever? Where are the gods waiting at the threshold with no strength to save themselves?

At best, we find gods of plague that are also gods of healing, but they lean toward healing because we would not have it the other way. The imagery of the messiah figure in Judaism waits at the outskirts of the city mending the bandages of the lepers. She is willing to be proximate to sickness. She has overcome the fear that keeps us far away from the sick and far from ourselves when we are sick.

As Susan Sontag gave it to us, “Illness is the night-side of life, a more onerous citizenship. Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick. Although we all prefer to use only the good passport, sooner or later each of us is obliged, at least for a spell, to identify ourselves as citizens of that other place.”

In many ways, Trump’s single-sided vision of power is akin to our own refusal of the wholeness of the human experience, our aversion to sickness, death, suffering, fear, depression, loneliness.

But when gods and leaders aspire to wholeness, they have the ability to perform for us the exalted position of any posture, be it anger, mourning, compassion, or sickness. A great leader would have taught us how to be sick this week, rather than pretend to be well. She would have reminded us that we are always dependent on the kindness and generosity of others for our personal well being. She would have shown us that it’s ok to be afraid and that illness can be a profound teacher of humility. She would have reminded us of our own fragility, and the preciousness of the life we’ve been given. How could we, with that wisdom inside us, not use our blessings to pursue goodness for all those with whom we share the world.

This is also the understanding we aspire to on Sukkot, this festival of transient hut dwelling. We go out from barricaded homes with foundations laid deep into the earth to sit and take meals in flimsy tents, pervious to rain and wind and destruction. That is what we are. Transient porous fragile creatures, gods of sickness, capable of healing, joy, creation, beginning, wholeness.

Wishing you a Shabbat Shalom and a Happy Sukkot!

Rabbi Zach Fredman writes and teaches from Brooklyn, NY. He is the bandleader of The Epichorus, purveyors of new Arabic folk and prayer music. Drawing from devotions in mythology and mysticism, Zach is translating Jewish wisdom from tribal roots to human futures. Connect at — zachfredman.com