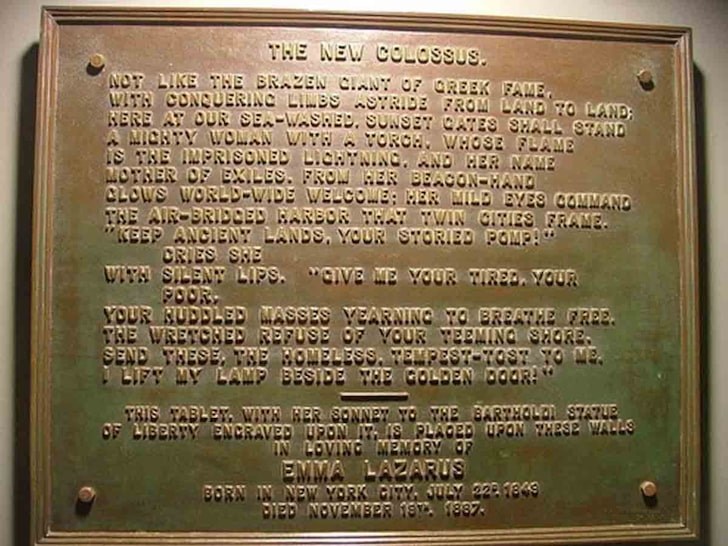

In 1883, Emma Lazarus gave the Statue of Liberty a voice. Her poem, “The New Colossus,” turned a towering figure of copper into a living symbol of refuge and hope: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.” But Lazarus was not just a poet—she was an immigration activist, deeply moved by the struggles of Jewish refugees fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe. What she heard about their harrowing journeys to America compelled her to use her words as a call to welcome the displaced. In a world where rules often drew harsh lines of exclusion, Lazarus envisioned a place where the weary could find rest and renewal. Her words didn’t reject the idea of rules—instead, they reframed it. The statue, strong and steadfast, became a gate of compassion.

The Hebrew Bible is no stranger to this balance. It holds in tension the unyielding strength of walls – laws that protect, boundaries that order life – and the open generosity of gates, through which mercy flows freely. Justice, as the Bible shows us, is not either-or; it is both-and. It demands accountability and compassion, structure and grace. In my time walking the streets of Jerusalem during my Stand and See trip with Clal, I saw firsthand the profound tension between the steadfast walls of tradition and the open gates of compassion. It reminded me that living within the covenant is not about choosing one over the other, but about holding both in sacred balance.

Rules are essential. Without them, chaos reigns. They give us security, define our responsibilities to one another, and create the frameworks within which communities can flourish. The law is, as the Psalmist writes, “a lamp to my feet and a light to my path.” It guides us and reminds us of who we are called to be. The Torah makes clear that the “stranger” who lives among the community is not exempt from these laws—they are bound to them just as everyone else is. This inclusion of the stranger reflects not only a sense of fairness, but also the belief that shared rules are the foundation of a just society.

But rules alone are not enough. They can also become barriers, misused to exclude or harm. In the 1920s, the United States sealed its gates, limiting immigration and denying refuge to those fleeing persecution. The law held firm, but compassion faltered. Only later did the nation recognize how much it needed the very people it turned away—how their strength, resilience, and creativity could have enriched the whole.

This is where the gates of compassion must temper the walls of law. For who among us has not fallen short? We have all, at some point, violated the rules, strayed from the path, or chosen the easy wrong over the hard right. Yet, when we falter, we long not for walls but for gates—an opening through which we can make amends, rebuild trust, and find our way back.

In my work with restorative justice, I have seen the transformative power of this tension. When someone violates the rules, they must be held accountable. The harm done must be acknowledged, and the consequences must be real. But the process cannot stop there. True justice asks what comes next. How do we repair the breach? How do we create space for growth and renewal? It is through these questions that communities move from punishment to healing, from exclusion to restoration.

This duality—walls and gates—is echoed in the covenantal themes I explore in Jewish-Christian dialogue. The law is the structure that sustains us, but it is the compassion of the covenant that invites us into deeper relationship. In Christianity, when the Pharisees questioned Jesus about the law, pressing him to clarify its greatest commandment, he did not dismiss the law but reframed it with profound simplicity:

“Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: Love your neighbor as yourself.”

Yet Jesus was not introducing something new—he was quoting the Jewish teaching of Deuteronomy 6:4-5, the Shema, recited daily in Jewish tradition. Rules matter in both traditions, but without love, they lose their purpose.

Today, as a society, we seem afraid to admit our own failings. There is a pervasive fear of being wrong, as if acknowledging imperfection were a sign of weakness. But when did we forget that life rarely moves in a straight line? The squiggly lines—the detours, mistakes, and moments of struggle—are where our shared humanity lives. Rules guide us, yes, but our imperfections and our willingness to own them are what connect us.

Emma Lazarus understood this. Her vision of the Statue of Liberty was not one of unbending perfection but of sturdy grace—strength paired with welcome, law tempered by mercy. She called us to create a society that upholds structure without losing sight of the people those structures are meant to serve.

In a time when immigration is increasingly tied to not only the law but to morality, and when the question of what the law says has dire implications for the health and welfare of so many, I want to bless us: May we build walls strong enough to protect, but never so high they cannot be opened. May we create gates wide enough to welcome, but never so loose that they lose their purpose. And when we falter—as we all will—may we find the courage to step through the gates, owning our mistakes and embracing the hard, holy work of restoration.

Jill Harman, MA, is the Associate Director of the Magis Catholic Teacher Corps at Creighton University, where she also teaches in the Department of Education. A restorative justice practitioner and ordained minister, Jill brings over a decade of ministry experience and has facilitated restorative work in schools, churches, and nonprofits. Her research explores the mentorship experiences of female clergy in the United Methodist Church. She is a 2024–2026 Sinai and Synapses Fellow and is passionate about faith, formation, and the common good.