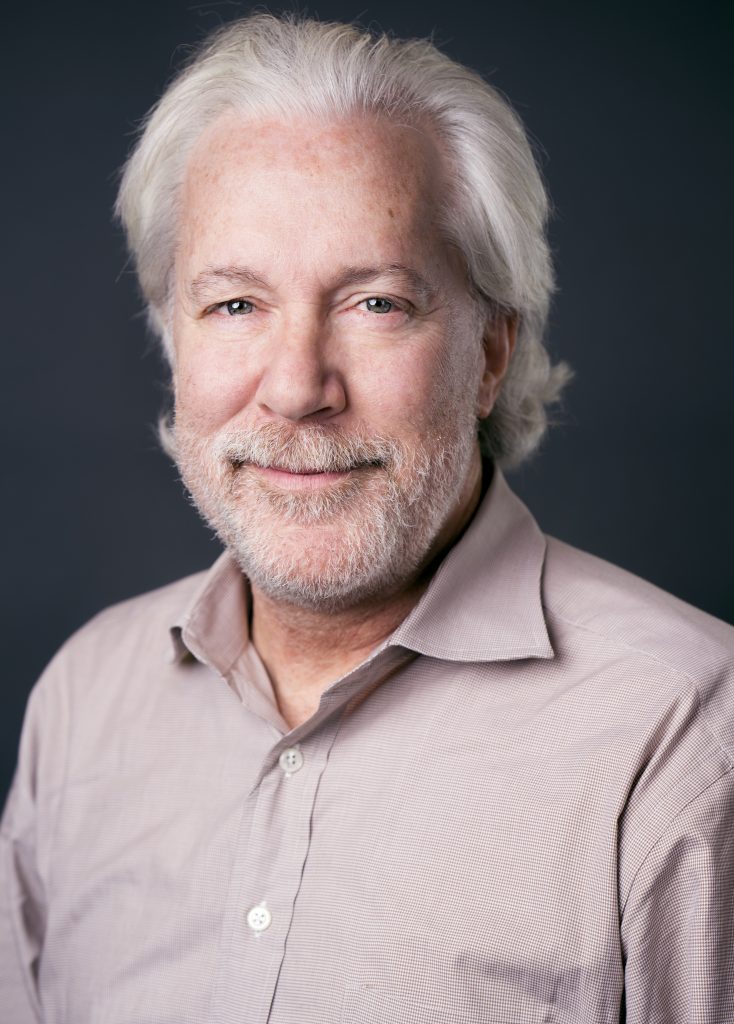

The following is a long-form piece by Clal’s President Emeritus, Rabbi Irwin Kula, on the Israel-Hamas-Gaza tragedy. Irwin decided that rather than edit this piece to get into other far more popular platforms (as requested by those platforms), he did not want to compromise his commitment to Clal’s unique and desperately needed ethos of a robust and challenging intellectual and psychological pluralism AND a deeply Jewish groundedness.

Trapped by Trauma: Transcending the Dragon’s Gaze

The devastating violence between Israel and Palestinians is another turn in the tragic cycle of destruction these two people seem doomed to endlessly inflict upon each other. However horrifying to justify Hamas’s atrocity as resistance and however justified Israel’s response as self-defense – and Israel is justified in responding to Hamas’s barbarous, nihilistic, and anti-semitic murderous spree of October 7th – the ensuing rhetoric, collective suffering, and innocent civilian deaths – especially the killing and maiming of thousands of children – is tragically familiar and hauntingly predictive of even more death to come. When the same language, tropes, narratives, accusations, hasbara, op-eds, PR, and earnest diplomatic and political maneuvers recur, when so many of the same players in a tragic drama repeatedly reenact the same destructive behavior, it signals that our understanding and judgment of what is happening – however right and even moral – is simply insufficient. In the face of the killing of children, everyone – even those “more” right – are also wrong.

Our dominant geopolitical and diplomatic frameworks — realpolitik, rational choice theory, zero-sum game theory — and our primary lenses, e.g., historical, political, economic, and even religious, can not break this 100-year cycle of violence, let alone achieve sustainable peace. Recent advances in cognitive science, e.g., the work of Daniel Kahneman and Iain McGilchrist, explain why: we are far less rational than we believe. Our views and opinions – our reasons and rationales – are intimately and integrally related to our feelings. Much of our “thinking” is an instantaneous response to unconscious emotions. When threatened, we are flooded by painful feelings like fear, anxiety, sadness, disgust, and shame. In response, the best of us, wherever we are on the political spectrum from reactionary/tribal to progressive/universal, defend against the too-muchness of our psyche by doubling down on inherited strategies that worked to get us to the present moment. But, by definition, our views can not include every aspect of a complex reality, and so we inevitably curate, filter, and exclude facts – the anomalies – that cause cognitive dissonance. When overwhelmed by painful and threatening feelings, we tend to carve the world into clearly defined right and wrong, good and evil, and turn our existing views into certainties. The most prevalent way to banish or numb painful feelings of vulnerability, precariousness, and shame – especially for young men 18-32 – is with self-protective expressions of aggression, rage, and violence. And intellectual aggression that cuts a person down, cancels people, or excludes them from the community can be as damaging to the body politic as the physical sword is to the body.

The Torah invites this realization right “In the beginning” when God, overwhelmed by disappointment in Adam and Eve’s eating from the tree, lashes out and banishes them from the garden. That this banishment is clearly an overreaction can be inferred by God clothing/protecting Adam and Eve as he exiled them. Then just a few chapters later in the story of Noah, God, flooded by disappointment and anger too overwhelming to digest, wipes out his own creations. So “disproportionate” is God’s response – however justifiable given it is God – that even God feels guilty, regrets his lashing out, and promises Never Again. Can we be expected to be better than God in digesting painful feelings of powerlessness, fear, revenge, sadness, disgust, etc., that overwhelm us and to which we respond and defend by lashing out with aggression and violence?

Most human beings are not pure villains, and very few people in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict are truly evil; all are trapped by trauma. Without claiming any moral equivalence between the Holocaust and the Nakba and the ensuing decades of dehumanization and violence perpetrated by Israelis and Palestinians upon each other, both sides’ identities and worldviews are anchored in trauma layered upon trauma. The deep drivers of this conflict are the less visible layers of unprocessed trauma and the shared inability on all sides to tolerate and digest feelings of vulnerability and shame. This includes those of us living outside ground zero of the conflict but who are deeply attached to one side or the other. The invisible is not to be underestimated. We can not fix the issues around this violent conflict with explicit first-level correctives because that is not where these issues live – though stopping the present eruption of violence is an absolute priority. The issues inhabit raw scars of previous generations, in things that happened so that we could actually be here and now…alas, we are here and now in trauma, suspicion, and bitterness that has grown in wounds that have never healed.

How do we attend to the unseen submerged processes? I can’t speak for Palestinians, but as a seventh-generation rabbi involved in Jewish life for 50+ years, I can suggest that Jews – whether Israeli or American – defended against the devastatingly painful feelings associated with having been the subjects of genocide in a remarkable collective self-reinvention. For Israeli Jews, this reinvention is reflected in the conventional story of the establishment of the State of Israel as a profoundly life-affirming reaction to the Shoah. A venture that tried to create a “New Jew” – a Jew who rejected the passivity and weakness of the Diaspora and cultivated Avners and Baraks and Yoavs – army generals, military heroes, and start-up nation entrepreneurs — rather than Avrahams, Yitzchaks, and Yaakovs. Israeli -Jewish identity found comfort, security, and safety in the acquisition and even glorification of military power and in a Jewish exceptionalism embodied in understandably declaring ‘fuck you’ to any criticism from a world that cold-heartedly failed to intervene during the Kingdom of Night. As a Zionist since as early as I can remember, with a father, z”l, who came here from Poland in February 1938 and often told the story of Menachem Begin coming to his parent’s home in Brest-Litovsk for a tea/gathering, I celebrate this protective, life-affirming response to the terror and shame of being a victim. But, like all defenses, it works as an adaptive skill until it doesn’t and then becomes maladaptive, self-destructive, and viciously lethal.

For Jews who came to America, this reinvention is reflected in the story of the exceptionalism of American liberalism, inclusivity, and pluralism that was the ladder to unprecedented Jewish power, affluence, integration, and influence. The majority of American Jews found comfort, safety, and atonement (from the guilt of surviving and even thriving during the Kingdom of Night) by acquiring and exercising political, financial, and cultural power – becoming accepted/white, if you will. This new collective American Jewish identity maintained Jewish distinctiveness not in any substantive commitment to Jewish wisdom, Jewish practice, or ethical aspiration but through building beautiful synagogues attended a couple of times a year, observing a few lifecycle celebrations, developing hyper-alert powerful defense agencies, emphasizing a collective fetishized pride in achievement (e.g. lists of Jewish Nobel Prize winners and Jews in the Forbes 400 that go viral) and cultivating an attachment to and Disneyfication of Israel that provided a vicarious yet powerful sense of security, satisfaction, meaning and purpose.

Jews and Palestinians understandably root themselves in disfiguring persecution narratives and in the distorting self-perception of being eternal victims. This breeds both terrifying nightmares of powerlessness and vulnerability and triumphant fantasies of power and invulnerability. Rarely, however, are we as powerless as our nightmares or as powerful as our fantasies. As powerless as Palestinians are, Hamas’s atrocity on October 7th upended the entire State of Israel and has generated supportive worldwide attention: this is powerlessness laced with quite a bit of power. As powerful as Israeli Jews are, with all their technological superiority, advanced weapons, and intelligence, they can not achieve the safety and security they want: this is power laced with quite a bit of powerlessness. Each side teaches their trauma to the next generation rather than heal it. Each side weaponizes their trauma rather than tend to and mend it. Each becomes the fire-breathing dragon they fear in the other.

However “necessary” and “justified” war – be it seen as preemptive, deterrent, revenge, resistance, terrorism or freedom fighting – killing each other over a material resource (land) or an idea is always a failure of imagination – a human failure. The psyches of the combatants are so wounded that trust and hope are irreparably broken, and a large segment of each people believe the only way to survive is murderous violence. In complex interdependent systems like the relationship between Israelis and Palestinians, where contexts and variables unfurl consequences and consequences of consequences in entangling and recurring processes everyone on all sides in the system are implicated in the drama. From terrorist to peace activist, from reasonable moderate to passionate extremist, from neutral observer to those walking away in despair, everyone contributes. We are all complicit in discernible and indiscernible ways of creating the enabling conditions for this tragic present moment to emerge. And the more vehemently we blame some other – right – left, left- right – however justified the blame may be, we are always also defending against feelings of complicity for where we are.

In religious language, this is the implication of Shema Yisrael, Listen very carefully, you who wrestle with Reality, Adonai Echad – EveryThing and EveryOne is interconnected. War then requires each of us, as individuals and groups, not to reflexively become more certain about our existing worldviews, beliefs, and opinions but to examine our own trusted categories, lenses, and frameworks. The relational interdependence of everyone and every view combined with the fact that we are presently killing each other’s children – whether in face-to-face grotesque atrocity or with impersonal 2,000-pound bombs from thousands of feet above the ground – implicates everyone in the Israeli-Palestinian drama. This includes Israelis, Palestinians, American Jews, Global Jewry, Arabs, Muslims, Democrats, progressive activists, Republicans, evangelical Christians, AIPAC, IPF, J Street, If Not Now, JVP, SJP, etc. If October 7th is as transforming an event in the history of Israel and the Jewish people as those from right to left attest, then we all need to do a deep dive into the insufficiencies of our own views. Our responses simply do not meet the shape of the trouble. We mistakenly perceive the atrocity of October 7th and the war on Gaza as causes rather than consequences. War – especially the slaughter and maiming of children at the magnitude we are seeing – demands self-questioning and tending to the psycho-cultural undergrowth and the multitudes of contexts embedded in contexts expressed in this violence. In the face of slaughtered children, every view at some level is idolatrous, and the more certain we are, the more idolatrous our view.

The identities and destinies of Israeli Jews and Palestinians are interdependent, and rather than tolerate the vulnerability this entails, they are trying to destroy each other. But the promise of violence and war is the illusion that we can eliminate vulnerability by eliminating the other. Violence only temporarily numbs the feelings of fear and vulnerability – it is like an opioid, addictive and generative of more violence. Killing cannot end killing. At best, it can give necessary space to these two peoples to do the psycho-cultural work of tasting, tolerating, and metabolizing feelings of vulnerability and precariousness, fear and sadness, and disgust and shame that come with life in general and with their/our own very painful particular histories. Until this work is done, not only can alternative possibilities and paths not be found, but far more terrifying is that engaging in peacemaking is actually more painful and risky than continuing to kill each other.

Jews across the political, religious, and cultural spectrum are being called on to heal the trauma of the Shoah and the history of victimhood while at the same time ethically exercising our unprecedented and overwhelming power. This is extremely difficult work to do given our trauma-induced nightmares of powerlessness that make the radically asymmetric power relations between Jews and Palestinians irrelevant, if not invisible. Our nightmares of powerlessness and vulnerability which immediately turned October 7th into Kishinev, if not Auschwitz, are understandable but a dangerous distortion of reality. As a nine-year-old boy in Grodno, Poland, my father hid overnight in an attic when two pogroms came through town. He woke up the next morning as powerless as when he fell asleep the night before, shivering in fear. Israeli Jews woke up on October 8th, unimaginably devastated by the atrocity committed by Hamas but with the fourth strongest army in the world already avenging and defending them. Trauma splits our psyche and politics in a most damaging, dangerous, and tragic way: between our need and yearning for protection, security, and safety and our need and yearning for compassion, care, and love. The maimed and dead in Gaza, and the maimed and dead in Israeli towns and kibbutzim, are victims of the same dark lusts. As Primo Levi wrote, and as we are seeing in real-time, “From violence only violence is born…as time goes by, rather than dying down, (violence) becomes more frenzied.”

The way forward is sobering: developing self-awareness, tolerating vulnerability, discerning contexts, and uncovering the submerged unseen causes for where we find ourselves. We often act – in destructive ways – not because we are evil – but because of the ways we have been acted upon. Against our conscious will that tells us: “Don’t do unto others what you don’t want done unto you,” we unconsciously, “Do unto others what was done unto us,” or even more viscerally we, “Do unto others that which we fear will be done unto us.”

To navigate the world without doing too much damage to each other requires integrating the parts of ourselves we repress and deny. Similarly, the ability of groups to move forward without doing too much damage to each other requires integrating the various psycho-cultural truths that are too hot to handle that each group denies or defends against. To put this most provocatively: the danger is not in the shadows but in the mirror. Neither we Jews nor Palestinians – wherever we are on the multidimensional continuum from left to right – can bear to look at ourselves in the mirror. As Leonard Cohen sings, “How can I begin anything new with all of yesterday in me.”

In a violent conflict, those with more power have a greater responsibility. This is especially challenging when the power is acquired in light of recent powerlessness and the experience of genocide – as the fear and anxiety (and shame) around vulnerability and safety is unbearable. In this case, and this is not a justification, dominance becomes seductive as it promises invincibility and the numbing of the painful feelings of vulnerability all the while blinding us to our own wounds. Eizeh hu gibor hakovaysh et yitzro – Who is the hero? The one who can restrain his primal impulses. The more power, the more restraint, not only because power corrupts but because power is always contingent. As the Torah suggests, Joseph was second in power to the Pharaoh and, with the best of intentions, wound up making the Egyptians avadim l’Pharoah/slaves unto Pharaoh…how devastating for the Israelites when those power arrangements shifted, and a new Pharaoh arose.

Peacemaking demands that leadership and the people on all sides in this conflict do the painful psycho-cultural work of understanding our shared trauma and recognizing the shared suffering we have perpetrated on each other. Within each of the Israeli/Jewish and Palestinian/Muslim body politics, no matter one’s view – everyone has a role in the drama and, therefore, psycho-political work to do. Somehow we have to carry our trauma and stay imaginative enough to rebuild a society that cares. Wherever we are on the political spectrum, we need to be suspicious of our own impulsive responses and, even more so, our tried and true solutions because while they seem to be most logical and rational, they are informed by the same dynamic of reaction and formation that created the problems to begin with.

The possibility of continuing generations requires discontinuing present ways of thinking. We need to dig deep and wide to search for our misplaced knowings, to find the scope of the illusions we have fallen into, to find the oversights and the erasures of each other’s truths and contexts…and there are always more contexts to perceive. In the face of thousands of killed and maimed children in a war that will not make Israelis any safer in the long term – as how many terrorists are being created every day this war continues – and that will irreparably stain the Jewish psyche in blood for the foreseeable future, we need to value “not knowing” with far more respect than “being right.” “We” need to realize how our prior experiences sift out new possibilities in familiar definitions and let possibilities we cannot recognize fall away. We each have to dig into, not simply, what is wrong with some other position but into the underlying root causes of our own views, into perspectives we are inevitably missing and excluding about the reality, and into the relational interdependence between our view and opposing views. No view is formed in isolation from some other view. Every view fails to include some partial truth – however partial – of an opposing view, which, when not included, often metastasizes.

Just like personal psychological growth is incremental, with breakthroughs happening only through “doing the work” of building one realization upon another, so is the process that enables groups to live together to tolerate the myriad of conscious and unconscious painful impacts we have on each other, and to heal the moral injury to our own psyches and souls that is a consequence of our oppressing and killing each other. The tragedy is that these two peoples who have experienced such similar psycho-social trauma and who both see themselves as hated by the world for no reason could actually heal each other – the other side of their ability to destroy each other. Their lives are intertwined. Neither people can have security without the other having security. Neither people can be liberated from the oppressor-perpetrator dynamic without each owning how the line separating good and evil passes through every human heart and every community. Somehow we have to be angry enough to fight and tender enough to stay sensitive to the nuances of mutual new learnings. We need to soften and deconstruct the exclusivity masking the vulnerability at the core of our identities. The question today is: what sort of human beings these two embattled peoples – Jews and Palestinians – will be after experiencing this latest cycle of devastating violence? Will we be shocked enough by what we have done to each other to accept and recognize the other’s love of this ever-illusive promised land alongside our own love? Will we have the psychological courage and moral imagination to dare and look into the abyss between us – whatever our rational world views and opinions – to find the hidden bonds of our shared vulnerability? For in the enemy’s gaze, we face ourselves.

Rabbi Irwin Kula is a 7th generation rabbi and a disruptive spiritual innovator. A rogue thinker, author of the award-winning book, Yearnings: Embracing the Sacred Messiness of Life, and President-Emeritus of Clal – The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, he works at the intersection of religion, innovation, and human flourishing. A popular commentator in both new and traditional media, he is co-founder with Craig Hatkoff and the late Professor Clay Christensen of The Disruptor Foundation whose mission is to advance disruptive innovation theory and its application in societal critical domains. He serves as a consultant to a wide range of foundations, organizations, think tanks, and businesses and is on the leadership team of Coburn Ventures, where he offers uncommon inputs on cultural and societal change to institutional investors across sectors and companies worldwide.

Rabbi Irwin Kula, addressed the endless cycle of Israeli-Palestinian violence through the lens of unhealed trauma in which each side “teaches their trauma to the next generation rather than heal it.” The underlying root cause of this conflict, he posits, is unprocessed trauma and the shared inability to tolerate feelings of vulnerability and shame.

Kula warns us to be alert to the underlying root causes of our own views and implores us, “to dig deep and wide in search for our misplaced knowings, to find the scope of the illusions we have fallen into, to find the oversights and the erasures of each other’s truths and contexts.”

I would like to explore a context beyond trauma which is an equally important root cause of the Israeli-Palestinian cycle of violence. It has to do with our stories about God.

Early on in his essay, Kula invites us to consider that even God had difficulty moderating “disproportionate” responses to the disappointment with human behavior. His examples are the banishment of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden and the annihilation of humanity, save Noah and his family, in the flood. Kula asks: “Can we be expected to be better than God in digesting painful feelings of powerlessness, fear, revenge, sadness, disgust, etc., that overwhelm us and to which we respond and defend by lashing out with aggression and violence?”

While clearly anthropomorphizing God, it is the following 5 words that caught my attention. In reflecting on God’s disproportionate response Kula adds: “however justifiable given it is God.” It is these 5 words that can catalyze us to “dig deep and wide for our misplaced knowings.”

“However justifiable given it is God.” Which is it then? Was God’s response disproportionate or was it justifiable? Kula attempts to ameliorate his labeling it disproportionate by suggesting that God felt guilty, had remorse for those excessive punishments. But those two stories in Genesis are not the end of what we could consider God’s (and humans) violent overreactions portrayed throughout the Bible. Trauma is not the only unprocessed piece of the equation. There are stories and beliefs which remain unprocessed, unrefined and which serve as ideological justifications for what is done in the name of God. If God’s overreaction is justifiable does that not give license to those believers in that God to see it as a model for their own disproportionate violence?

Beyond the trap of trauma is another trap. We need to examine those shared stories about God in Jewish and Muslim and other traditions—stories of disproportionate responses and sanctioned traumas that are justified because God is the one who is dispensing them. It comes down to this: For those who have inherited a religious tradition we have to unearth what is important to preserve and what needs to evolve about our stories of God; our stories of a God who privileges some and punishes others, our stories of a God whose honor can be affronted, our stories of a God who demands retribution and vengeance. Only then can human consciousness evolve, at least to the point that dehumanizing violence or violence that dehumanizes is no longer an endless cycle. Only then can trauma have fertile soil in which to fully heal.

I agree with so much of what my old friend, classmate and colleague Rabbi Kula has written here. But even though he zeroed in on the issue which has taken me out of the call for empathy and the ceasefire camp after decades of voting for the peace camp in Israel, I find his process stuck where we were on October 6. As a long time resident of Ashkelon I do fear “what will be done unto” us. That doesn’t mean I want to inflict suffering on innocent Gazans (a likely oxymoron as today we realize how many enabled the butchers) but a ceasefire means that in a few years my family will be targeted not only by missiles but by the butchers who murdered several friends on October 7. After accompanying my son to Kfar Azza to see what he is responsible for rebuilding I realized that Ashkelon is the new front line. A cease fire means in a few years the murderers will be at my door. They will not care how many times I demonstrated against our government and for a Palestinian state. And so I do fear what they might do to my children and grandchildren as Hamas has already promised several times since the massacre. So, as of today, I support whatever it takes to rid Gaza of Hamas. And at that time I will look for new partners for peace. Real partners for peace. But my salvation will not come from dispassionate intellectual analyses from abroad of how both sides need to suck it up. It will only come from assessing whether or not I still need to fear the savagery of my neighbors to the south in whom I was once ready to entrust my family’s future welfare. Should Irwin want a tour of Kfar Azza in order to understand the unacknowledged paradigm shift that took place on October 7 I will readily arrange that for him.

Thank you, Rabbi Matt Futterman. You, your family, your neighbors, your fellow Israelis (Arab and Jewish) live with the ever present threat from Hamas and other like-minded Palestinians. It renders Rabbi Kula’s fantasies about both sides evolving irrelevant to the real situation. Dr. Einat Wilf and Adi Schwartz in The War of Return demonstrate how Israeli/Jewish sovereignty over land from the Mediterranean to the Dead Sea is such an affront to Palestinians and other Arabs that their true quest, their motivating drive is to eradicate Israel and to kill Israelis and Jews. They never wanted a piece of land. They wanted the whole land because that would get rid of Israeli sovereignty. I asked a good friend who had a high position in the Israeli army and is now in his 60’s what he thinks of the future. He told me that he was hoping that his grandchildren would not have to serve in the IDF and fight the Arabs, but now he has come to the sobering realization that they will. It is heartbreaking that children have died in this war, but this is the Middle East. Hamas and their ilk see weakness as an invitation to conquest, murder, rape, behead, etc. as they did on October 7. By inflicting significant damage to Hamas’ terrorist army and infrastructure, they might think twice before picking a fight with Israel the next time. You, your family, your neighbors, and fellow Israelis are in our hearts.