When your small island nation has conquered and colonized much of the known world, making you and your cronies rich beyond measure, and you have a slew of navies to do all your work – from shoeing your horse to buttoning your shirt – you are likely to fall victim to melancholy. The cure? Build a hermitage on your land, hire a scruffy old man, dress him up like a druid, and invite your friends over to watch him putter about the place.

The “We are so rich we are sad, so let’s get a pet hermit” phenomena (otherwise known as ornamental hermits) occurred in England in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Hermits had long held a fascination for the educated well-to-do, and were viewed as otherworldly figures imbued with sacred knowledge due to their willingness to forgo earthly pleasures in favor of contemplation.

Some tried living the life of a hermit themselves, but when that proved too onerous, holiness by association had to suffice; and so, they did what they always did when they didn’t want to do something, they hired someone else to do it for them.

How might one go about hiring a human garden-ornament? By advertising in the local paper of course. One such ad was placed by the Hamilton family of Payne’s Hill in Surrey, which stipulated the successful applicant must…

continue in in the Hermitage seven years, where he would be provided with a Bible, optical glasses, a mat for his feet, a hassock for his pillow, an hour-glass for his timepiece, water for his beverage and food from the house. He must wear a camlet robe, and never, under any circumstances, must he cut his hair, beard or nails, stray beyond the limits of the Hamilton grounds, or exchange one word with the servant.

Should he remain the full seven years, the lucky fellow would receive 700 guineas (I tried to work out how much that is in today’s money, but I got very confused). Reportedly, one fellow gave it a go, but only lasted 3 weeks – before he was caught nipping to the local tavern for a quick pint, and was dismissed without so much as a brass farthing.

The Powys of Marcham in Lancashire, also in the market for a hermit, promised £50 a year for life, to anyone willing to live underground and have no contact with other humans for seven years. A commodious apartment (read, grotto) underground was offered, and as many books as the person could read, as well as a cold bath and a chamber organ. Despite such a tempting offer, the longest anyone managed to stay was four years.

Not only did the gentry advertise for hermits, but hermits also advertised for gentry; like Mr. S. Lawrence of Plymouth, who wrote:

A young man, who wishes to retire from the world and live as a hermit in some convenient spot in England, is willing to engage with any nobleman or gentleman who may be desirous of having one.

One of the most famous ornamental hermits was Father Francis of the Hawkstone Estate in Shropshire. A 1784 guide of the Estate described its prize attraction as follows:

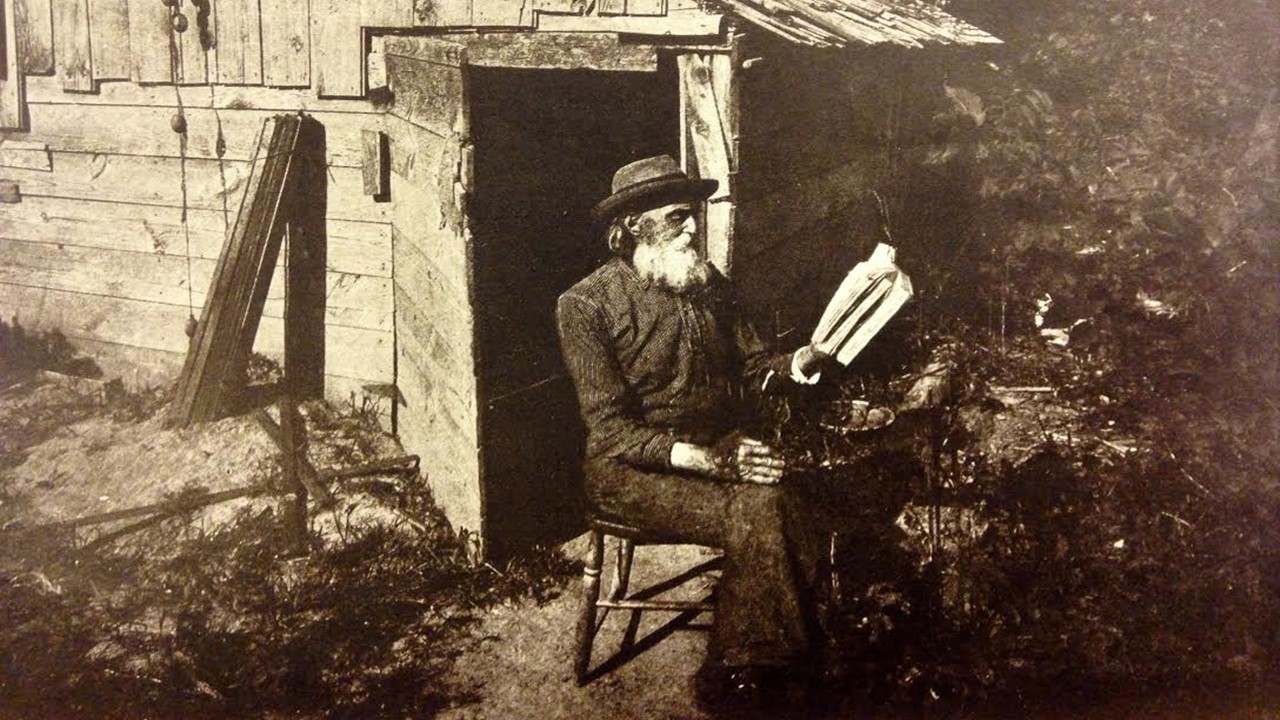

You pull a bell, and gain admittance. The hermit is generally in a sitting posture, with a table before him, on which is a skull, the emblem of mortality, an hour-glass, a book and a pair of spectacles. The venerable bare-footed Father, whose name is Francis (if awake) always rises up at the approach of strangers. He seems about 90 years of age, yet has all his sense to admiration. He is tolerably conversant, and far from being unpolite.

Upon his death, Father Francis was replaced by an automaton, which didn’t prove quite as popular as its real forebear, as one tourist wrote:

The face is natural enough, the figure stiff and not well managed.

Providing a hermit for the amusement of one’s guests was an idea that also occurred to Mr. Gilbert White of the Selborne Estate, who managed to convince his brother, Reverend Henry White, to forgo his clerical garb for that of a hermit’s robe. One guest, who was indeed greatly amused, was a Miss Catherine Battie, whom wrote (punctuation-less) in her diary:

In the middle of tea we had a visit from the old Hermit his appearance made me start he sat some with us & then went away after tea we went in to the Woods return’d to the Hermitage to see it by Lamp light it look’d sweetly indeed. Never shall I forget the happiness of this day.

By the early 1800’s, the acquisition and display of Ornamental Hermits had fizzled out, in conjunction with prevailing tastes in landscape architecture, which had changed significantly from the previous century, as well as preference for industry over contemplation. Of course, the landed gentry liked a hard day’s work about as much as they liked hermiting, so, naturally, they hired others to be industrious for them.

Sources:

France, P (1997) The Insights of Solitude, Pimlico, London pp. 86-9

Colegate, I (2002) A Pelican in the Wilderness: hermits, solitaries and recluses, HaperCollins, London pp. 186-8

Rebecca is a painter, collage artist and writer. Originally from New Zealand, she now lives on a little Island in the Irish Sea. She has a degree in Religious Studies and is passionate about religious history, philosophy and esoteric goings on. Her favourite research topic is peculiar religious figures; those people who, through their devotion and vision of the divine, challenged the religious establishments to which they belonged, sometimes being crushed by those establishments, other times irrevocably changing them.

You can contact her and/or find her artwork and other writing on her website rebeccaodessa.com