Hate comes from the old English word, hatian (meaning: regard with extreme ill will) via the Proto-Germanic word, hassen (the root of which means: grief, sorrow, calamity). This old root meaning offers insight into understanding the nature and origin of hate, suggesting its source is loss. Losing something we are attached to and which gives us a sense of security and identity, can create a vacuum – a raw, gaping wound that cries out to be filled. We can fill that void with one of two things: something creative, or something destructive. Most of the world’s astounding artistic, intellectual and humanitarian endeavours have been the result of grief-stricken soul-seeking redress. Likewise, and sadly, the most profound human destruction the world has ever seen comes from the very same.

Hate is often born of injustice, and first resembles righteous indignation, which, if smothered by powerlessness, can putrefy into a stinking mass of resentment, corrupting the soul and destroying all in its wake.

Petrified resentment, turned hate, brought about by a loss of face, is the axle around which the following story turns. And if hate is the axle, hysteria is the wheel. Hysteria is the physical manifestation of psychological disturbance; from the Latin, hystericus (meaning: of the womb – indicating hysteria was once considered a solely female affliction, a theory thoroughly debunked by countless examples of the mass-hysterics of men).

On the surface, and from a distance, hysteria seems silly and immature; but at its core, and up close, it is dangerous. Indeed, when collective, sanctioned by authority and harnessed to hate, hysteria is a force so insidious, so twisted, it can tear the innocent in two, wipe their blood on the sky, and call it good. Moreover, it can spread.

The following story is disturbing in its detail, horrifying in its injustice and revolting in its hypocrisy. It is a true story.

Setting:

A little French town called Loudun, in the early part of the 17th century

17th century Europe was not a fun place to be, sandwiched as it was between the Reformation (16th century) – which eviscerated the soul of Europe – and the Enlightenment (18th century) – which turned her on her head. The turmoil created by these two forces spawned an unprecedented crisis of faith, widespread economic upheaval and the disintegration of the collective world view.

Although it was a precarious time for all, most at risk were old women with sharp tongues, suspicious moles, and minds of their own. The witch craze was in full swing; a truly shocking phenomenon which gripped Europe for over 200 years and brought about the death of between 80,000 to 200,000 people. Although most victims of the witch craze were women, our story concerns a man, a very handsome man.

Characters:

Urbain Grandier

Urbain Grandier (1590 – 1634) was renowned for his physical beauty; making him, in equal measure, a hit with the ladies (something he actively encouraged) and a source of rabid envy with men, especially husbands. As well as being handsome, he was intelligent, well-born, ambitious, and eloquent. He was warm and charming with friends, but sarcastic and dismissive of those whom, by his own reckoning, did not live up to their high opinions of themselves. This made him vulnerable to the machinations of people in power who felt threatened by his charismatic presence, especially when they were on the receiving end of his caustic wit and astute assessment of their failings.

Receiving a first-class Jesuit education and showing a prodigious knack for languages and persuasive rhetoric, Grandier opted for a career in the church. Though intellectually suited to the priesthood; on a physical level (namely, sexual), he proved to be less than an ideal – given that such a role required he be celibate, which Grandier most certainly was not. Indeed, he was rumoured to have fathered a child and married a woman (not the mother of the child), and to have dillydallied with several townswomen, much to the ire of husbands and fathers alike.

Further, he made no secret of his views on celibacy – which were that it was a physical impossibility for virile men – even writing a lengthy treatise of the subject, which, in part, served as his undoing. Not that a priest having it away with his parishioners was anything new, or warranted censure; rather, espousing views on the subject, counter to those of the church, and worse, making them public, was far from acceptable.

While his open criticism of celibacy was eventually used against him, the true source of his undoing was the fact that he was a cut above everyone else in all respects; he knew it, and everybody else knew it too; but, rather than being content with his obvious superiority, he demanded it be acknowledged by all and sundry, especially his foes. For them, such a prospect was intolerable; so, instead of kowtowing to him, they plotted his downfall.

Father Mignon

Father Mignon was an insecure, petty and vindictive man, and the person most responsible for Grandier’s demise. Not much is known about him, other than his relationship to Grandier – something, I’m sure, gets on his goat to this day.

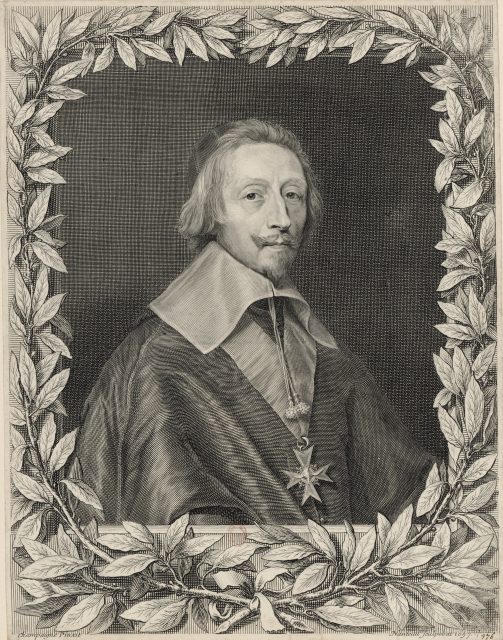

Cardinal Richelieu

Cardinal Richelieu (1585 – 1642), the chief minister of France, was considered by all – including history – to be the power behind the throne of King Louis XIII. A formidable enemy, Richelieu’s role in Grandier’s demise, while not huge, was certainly decisive. As with Father Mignon, Richelieu bore a long-standing grudge towards Grandier, and, rather than let time and his rise to power diminish that grudge, he let it fester, until, unlike Mignon, who destroyed Grandier because he needed to, Richelieu destroyed him because he could.

Jeanne des Anges and the Ursuline nuns

Jeanne des Anges was the mother superior in a convent of Ursuline nuns in Loudun, and the chief protagonist (read, pawn) in Father’s Mignon’s dastardly plan to ruin Grandier. Reputably hunched back and funny-looking, and given to wanton lust, Sister Jeanne originally took a shine to the attractive and erudite Grandier, requesting that he be the convent’s Father confessor. Grandier had the good sense, but ill-fate, to say no; thereby offending the delicate sensibilities of Sister Jeanne – taking, as she did, his refusal as a personal slight. She then went on to ask Father Mignon to fill the post. Father Mignon, being equally insecure, took it as a request to play second fiddle to the smug and too-big-for-his-boots Grandier. Still, the prospect of ruling over a gaggle of vulnerable women was more than he could resist, so he took the post, and Grandier’s fate was sealed.

As for the rest of the nuns: a group of saintly women devoted to God? Think again. Back in the 17th century, women weren’t so much called to a life in the convent, as they were dumped there. Daughters of noble families that had fallen on hard-times, without the means to secure a good marriage, were surreptitiously shipped off to the local nunnery to live their lives in controlled austerity and abject boredom. Hence, the nuns of the Ursuline convent in Loudun were silly and restless, and in desperate need of male attention.

The Devil

The Devil (aka Satan, Beelzebub et al) played a starring role in the Urbain Grandier story, as he did in much of 17th century Europe. As the manifestation and progenitor of evil, the Devil was responsible for all that was untoward, anti-church, confusing, a little bit suspect, or just plain unknown. Crops failed? The Devil! Aunty Flo died in a coughing fit? The Devil! Sweetheart ran off with the blacksmith’s son? The Devil! How could the Devil do all these things? Why, by enlisting the help of his demon-coerced, pact-signing, human agents of evil of course – otherwise known as, witches.

Narrative

Harassment

As with all biographical narratives, events happen one after the other in such a way that, in retrospect, they appear to seamlessly lead into each other, with the outcome as certain in the beginning as it is in the end. Thus, looking back, we can see Urbain Grandier, heedless of the warnings of his friends and benefactors, moving inexorably toward his fate; making one decision after another that, in his stubbornness and his pride, placed him within easy reach of the grip of his ruthless enemies.

As well as prideful and stubborn, Grandier was inflexible and litigious, and exacting in his collection of reparations for wrongs done to him. As such, when a fellow priest hit Grandier with a stick (in response to an insult the dashing father had leveled at him), Grandier, instead of taking it like a man, took the man to court. The man, in cahoots with the dastardly Mignon, counter sued; accusing Grandier of corrupting all the woman in the town, neglecting his priestly duties and turning God’s sanctuary into a den of iniquity. Unfortunately for them, and lucky for Grandier, they over played their hand; for, in a trial that lasted 2 months, not a single woman could be found to give evidence against him.

Initially found guilty of the charges, Grandier, on appeal, was eventually pardoned. The Bishop of Bordeaux, who overturned the conviction, warned Grandier that his enemies were many and not without power, and that he would do well to conduct himself with humility; astutely surmising that, should the good father come-a-cropper, it would be through pride.

Did Grandier heed his words? Did he heck! They went in one ear and out the other; and far from backing down, he charged forward, demanding his name be cleared and his accusers make restitution, in full, in public and in disgrace. His enemies were incensed and their hatred galvanised; on conceding they had lost round one, they immediately set about plotting round two

They didn’t have to wait long, for there was a ghost in the nunnery.

Accusation

The ghost, it turned out, was a couple of novice nuns, intent on enlivening their otherwise dull existence. Father Mignon, rather than castigate the pranksters and demand that they stop, bade them continue, enjoying, as he did, the role of manly shepherd presiding over his delicate flock. More nuns got involved with the charade, including Sister Jeanne, until the nunnery was run amok with ghosts, their nightly exploits becoming increasingly lewd in nature. And then, quite by chance (or perhaps design), the name of the chief fornicating spectre was revealed: Urbain Grandier.

Had Grandier’s name not been pronounced in answer to Father Mignon’s question – whom doth ravage the so – the whole debacle might have died away, but the pronouncement was too delicious, and Father Mignon, seizing upon the opportunity, declared witchcraft was afoot and demanded that full and bona fide exorcism take place.

Exorcism

And, so it did. What a spectacle it was: nuns writhing on the floor, squealing and playing with themselves, the entire town in attendance, watching in delighted titillation, the exorcist shouting over the tumult, demanding the demons name their human cohort, and Father Mignon, rubbing his hands with glee every time “Urbain Grandier” came in reply.

When Grandier got wind of the goings on, he shrugged them off as ridiculous; until they kept going on, and he was compelled to get involved. He insisted he be allowed to address the demons himself, and when he did, he quickly uncovered the specious nature of the possessions, not least because the demons could not speak Latin. According to Church law, demons could, at will, speak all known languages; however, it was clear that the demons of Loudun were unable to conjugate Latin verbs, let alone speak Hebrew or Welsh.

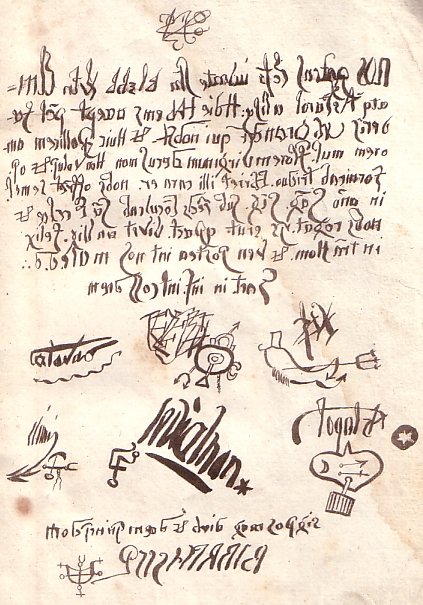

The exorcist, at Mignon’s behest, pressed on, and soon concrete proof of demonic possession, and Grandier’s involvement, was produced; or, to be more precise, vomited. It was Sister Jeanne who heaved up the proof in question, which consisted of the ashes of a consecrated wafer, the heart of a child (allegedly killed during a ‘Witches Sabbath’ ritual), semen (supposedly Grandier’s) and a copy of Grandier’s pact with the devil, signed by himself and several demons.

For Grandier, this was the last straw; his accusers had gone too far, and he demanded the authorities get involved. They did, and, after a thorough investigation, the possessions were deemed bogus, and Grandier was exonerated.

This should’ve been the end of the matter; but Grandier’s accusers would not let it go. The avenue of civil authority may have been closed to them, but they still had the church. So, in a move that would prove fatal for Grandier, they went straight to the top; and, at the top, was none other than Cardinal Richelieu. Still licking his pus ridden wound from yonks ago, Richelieu was more than happy to oblige the conspirators. A new trial was ordered, wherein reason was exiled, and all hope for Grandier was lost.

Witch Trial

Sister Jeanne and the nuns did not take part in the new trial; indeed, they recanted their previous statements, claiming they had made it all up. They begged to be allowed to speak in Grandier’s defence, but their pleas fell on deaf ears. Sister Jeanne suffered terribly for her part in the whole debacle (rightly so), until guilt-ridden and unable to live with the consequences of her wicked game, she tried to hang herself from a tree in the Abbey; narrowly surviving due to the lifesaving actions of her fellow nuns.

The parameters of the new trial belonged to the preceding centuries, and were based, not on law, but on the Malleus Maleficarum – the medieval how-to-manual for identifying and punishing witches. As per the manual’s instructions, the first order of the day was finding the mark of the devil. To do so, Grandier was stripped and a pricker was called. A pricker was employed to prick the moles and/or marks on the body of a suspected witch; if the prick caused pain and bleeding, they were deemed legit; if, on the other hand, pain and blood were absent, it was a sure sign witchcraft was afoot.

The story goes that the pricker in Grandier’s trial used a retractable pricking device, so that, the sharp point, when pressed against his skin, retracted into the handle, thereby causing neither pain or blood. It was a dirty trick, and it, along with the vomited pact and a copy Grandier’s treatise concerning the impractical reality of celibacy, condemned the vital and gifted young priest to death. But not before he was maliciously tortured.

Torture

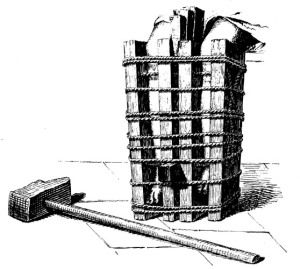

Torturing convicted witches was standard practice – as laid out in the Malleus Maleficarum (lit. Hammer of Witches) – the impetus for which was twofold:

- To illicit a confession – not to alter the outcome (once convicted, they were going to die); rather, to mitigate the brutality of their death, and to serve as justification for their torture and impending death.

- To extricate the names of fellow witches – hence why Europe found itself with a witch craze: find one witch, find a whole bunch.

Grandier was sentenced to the extraordinary torture, also called, brodequins; a torture so catastrophic, the victim invariably died within a few days of undergoing it (as such, it was only meted out to those condemned to death). Placed in a seated position, flat wooden boards were tethered to the inside and outside of Grandier’s legs; 8 wooden wedges were then successively hammered in to the space between his legs with a heavy mallet, thereby constricting and, eventually crushing his legs. Actually, pulverising would be a more accurate description; indeed, it is recorded that, when the 7th wedge was slammed in, Grandier’s legs burst open and blood and marrow spurted in the face of his torturer. By the 8th, his legs were as flat as the boards they were tied to.

Far from confessing to witchcraft, let alone implicating other people, Grandier, in-between bouts of unconsciousness, his eyes lit with anguish, maintained his innocence and prayed prayers so earnest and so true, some of those present were visibly moved.

Death

His legs now a useless mass of pulp and gristle, Grandier was placed in a small cart and pushed to the place of his execution: a pyre in the town square. Originally condemned to be hanged and his body burned, the executioner decided it would make for a better spectacle to burn him alive – a spectacle the whole town had turned out to watch.

Unable to stand, Grandier was affixed to the post with a metal hoop. His friends managed to have a rope put around his neck, in the hope that it could be pulled upon to quicken his death; but some particularly zealous (read, sadistic) monks in attendance prevented that from happening; the same monks also threw water in Grandier’s face each time he went to speak – a right granted the condemned – thereby reducing his final words to a spattered garble.

In his final moments of his life on earth, as flames violated the nerve endings in his flesh, causing him to writhe in agony, Grandier, demonstrating the true measure of his worth, raised his voice in prayer, and asked God’s forgiveness for all. He then hung his head on his chest and died.

Aftermath

After Grandier’s death, the possessions continued for a time, with sister Jeanne reprising centre stage (having learnt nothing from her guilt-ridden suicide attempt). But, once all the hoopla had died down, it was understood by most that a travesty had occurred. Indeed, in a matter of decades, Grandier’s story was cited by enlightenment thinkers as evidence as to the preposterous nature witchcraft and demonic possession, thus bringing a halt to the witch craze in the late 17th century.

Postscript:

It is a mistake to believe that Urbain Grandier’s story belongs in the past. That we can hear it and be aghast at how paranoid and superstitious people used to be, and marvel at how far we have come in our understanding of the world. The truth is, when it comes to shedding innocent blood, and calling it good, we are still at it. We point our finger at that which we fear will destroy us, and declare we have the right to destroy it first; not realizing the real danger to our survival lies not in external forces, but in that which is within us: our greed and our fear and our will to power.

However, Grandier’s story is more than a lesson in the destructive power of human nature; it is a story of the triumph of the human spirit, and the indestructible strength of the human soul. When tortured far beyond all limits of endurance, when harassed and humiliated, slickened by cruelty, and set alight in malicious hate, Grandier did not give in to the darkness, but opened himself to the light. His enemies may have mangled his body, but they could not mangle his soul; moreover, in a crucible of unimaginable terror, he died with his faith intact.

Grandier could have punished his murderers and the bystanders at his death, who reveled in his agony; he could’ve used their fear of demonic forces against them, raining down curses, thereby causing them irreparable psychological suffering. Instead, he asked God to forgive them; knowing they lacked true understanding of what they were doing: that it was not he they were destroying; but themselves; and for that, Grandier, in his own torment, looked upon them, not with hatred, but with compassion.

Urbain Grandier’s story is one of extremes; and, ultimately, it is about choice, a choice we all have.

Sources:

Ruiz, Prof. Teofilo F. (2002) The Terror of History: The Witches of Loudon, University of California, Los Angeles

Rebecca is a painter, collage artist and writer. Originally from New Zealand, she now lives on a little Island in the Irish Sea. She has a degree in Religious Studies and is passionate about religious history, philosophy and esoteric goings on. Her favourite research topic is peculiar religious figures; those people who, through their devotion and vision of the divine, challenged the religious establishments to which they belonged, sometimes being crushed by those establishments, other times irrevocably changing them.

You can contact her and/or find her artwork and other writing on her website rebeccaodessa.com