There’s a classic story attributed to Hasidic literature about a young boy who would wander around in the woods. His father got concerned as he went deeper and deeper into the forest each time, so one day, he said to the boy, “I notice that every day you walk into the woods. Why do you go there?”

The boy replied, “I go there to find God.”

“That’s wonderful. But don’t you know that God is the same everywhere?”

“Yes,” the boy answered, “but I am not.”

Whether or not we see God as the creator of heaven and earth (and, by extension, everywhere), the authors of the Torah certainly did, which presents a question for this week’s portion Terumah, where God tells the Israelites to “Build for Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them” (25:8). If God is everywhere, why does there need to be a specific place for God to dwell? Is God contained in just that one place?

The story above can help us resolve that contradiction – God may be everywhere, but our interactions with God are much more localized. And while much of the Mediterranean religious world had specific places where their gods dwelt, in Judaism, the God of Israel was wherever the people happened to be. While meeting with God would happen in only one place, that one place would be portable.

In fact, there is an even more specific place where God is said to come down to talk with the Israelites in this week’s portion. After getting a list of materials and processes for creating the Mishkan and its surrounding ritual elements – gold, silver, multi-colored yarns, and animal skins; poles, tables, cloths, the lampstand, and the altar – we are told precisely where God would dwell when it came time to talk to the Israelites: “from above the cover, from between the two cherubim that are on top of the Ark of the Pact.” (25:22)

In other words, it is important that the cherubim are to face each other (v. 20) so that God would dwell in that small empty space between them. The great commentator Rashi emphasizes the precise dimensions of this space: “you shall not make their wings touching the body but spreading on high slightly above but almost on the same level with their heads so that the hollow space between the wings and the cover shall be ten handbreadths.” The Israelites could not create a closed space; there had to be an opening for God to come down in order to visit them.

Indeed, the Mishkan, the sanctuary, is built to be a place where God will “meet with you…and there I [i.e., God] will command you concerning the Israelite people.” (25:22) That little gap wasn’t there to make us feel God’s majesty. The awe and wonder was when the Israelites saw the lightning and thunder on Sinai. Instead, this very small space was to be a place where the Israelites would learn about how to follow mitzvot. It wasn’t majestic; it was much more mundane. But that’s where day-to-day life would be happening – if Sinai was a wedding, with all the pomp and circumstance, then the mitzvot was all about who would pay the bills, do the dishes, and pick up the kids from tae kwon do. That small space would allow them to learn how to live and create a holy community.

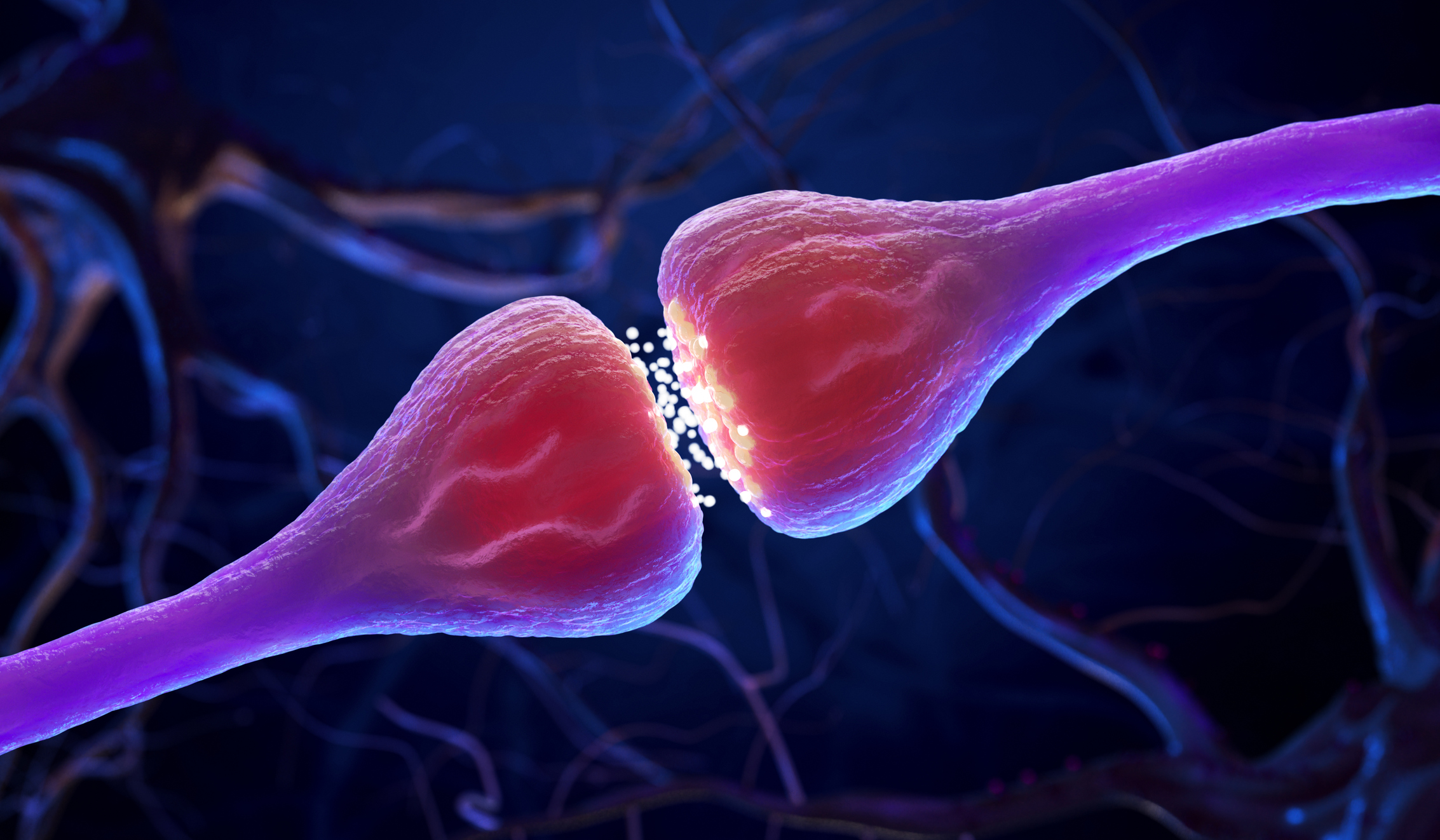

In many ways, the image of the cherubim facing each other, with a gap in between for God to dwell, also evokes a more recently construed image from science – a synapse. Synapses in the brain are key for memory development since they’re the place where neurons pass from one to the other. Neurons are the nerve cells in our body, and the “synaptic cleft,” as it’s called, is an empty space that allows the neurons to “talk” to each other across it. The gap is crucial for communication and transmission. As described in the excellent (if slightly simplified) summary from the Khan Academy:

A single neuron, or nerve cell, can do a lot! It can maintain a resting potential–voltage across the membrane. It can fire nerve impulses, or action potentials. And it can carry out the metabolic processes required to stay alive.

A neuron’s signaling, however, is much more exciting–no pun intended!–when we consider its interactions with other neurons. Individual neurons make connections to target neurons and stimulate or inhibit their activity, forming circuits that can process incoming information and carry out a response.

How do neurons “talk” to one another? The action happens at the synapse, the point of communication between two neurons or between a neuron and a target cell, like a muscle or a gland…

For both the dwelling place of God and the neural activity in our brain, the empty space in between is what allows for learning to happen. Now, that “empty space,” and allowing for opening up, can be scary. Vulnerability entails the potential to get hurt. Learning new ideas means our beliefs get challenged. We discover where we disagree with others. We see where we may have been wrong and where we have failed.

But we still need the empty space. We need the opening. In both the Mishkan and our brains, the place where nothing seems to happen is precisely where all the action happens. The “emptiness” is dynamic, allowing for new combinations of ideas, creative solutions, and deeper relationships. And while God may be everywhere, leaving it at that would make for a static God. Instead, we can strive to see the places and ways in which we experience God as unique, particular, and local. May that empty space be a place where – and how – we can change, grow, and, most of all, learn.

Rabbi Geoffrey A. Mitelman is the Founding Director of Sinai and Synapses, an organization that bridges the scientific and religious worlds and is being incubated at Clal – The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership. He was ordained by the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion and served as Assistant and then Associate Rabbi of Temple Beth El of Northern Westchester. In addition to My Jewish Learning, he’s written for The Huffington Post, Science and Religion Today, and WordPress.com. He lives in Westchester with his wife, Heather Stoltz, a fiber artist, and their daughter and son.