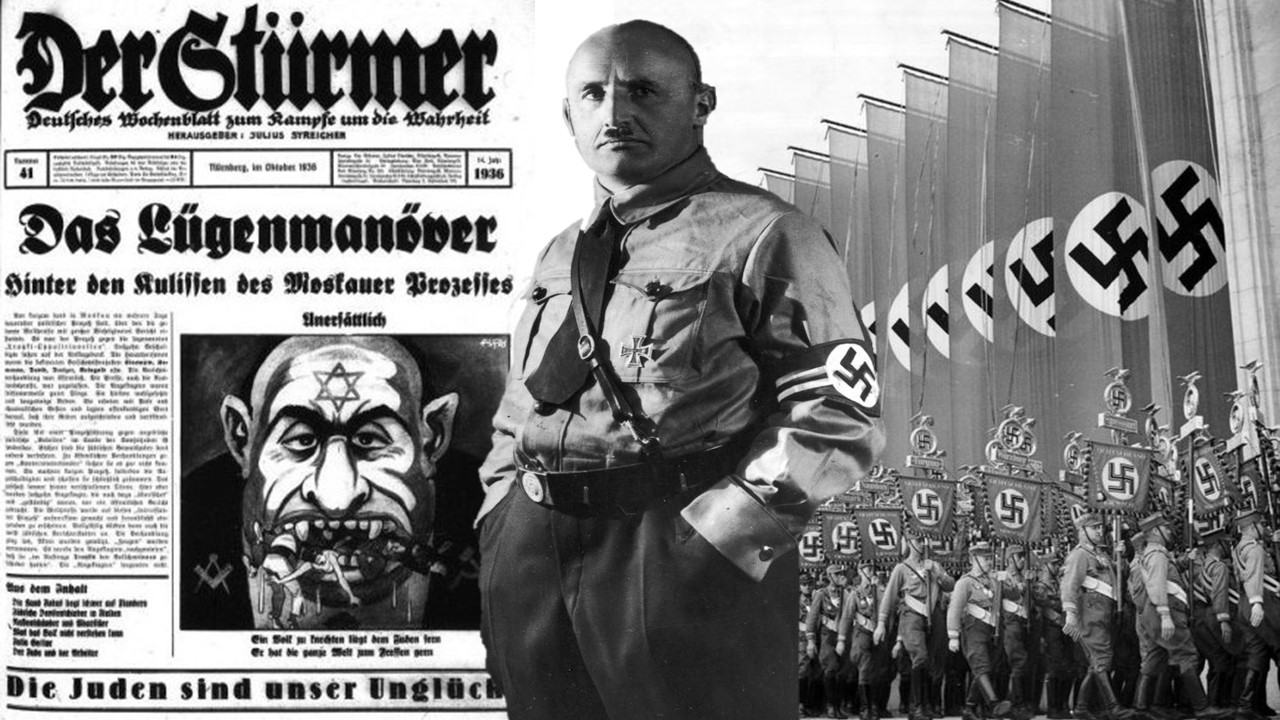

Julius Streicher was the creator and editor of Der Sturmer, the notorious anti-Semitic newspaper of the Nazi era. He was a hateful bigot of mediocre intelligence, loved by his leader and despised by his fellow Nazis, not for his moral repugnance, but because they generally despised each other. Streicher’s hatred of the Jews was profound and malignant, his ideology rotten to the core, full of lies and contempt. Arrogant and cruel, Streicher showed no remorse for the hatred he spread or the devastation it wrought; rather, he reveled in it and pushed on, until all of Germany was infested with the foul stench of his hatred.

Born February 12, 1885 in the Bavarian town of Fleinhausen, Streicher’s childhood was poor, but happy. The youngest of nine children in a devout Catholic family, his mediocre intelligence ensured he matured into adulthood with a mind that was small and coarse. Though he knew no Jews growing up, his Catholicism provided fertile soil for his later hatred, courtesy of the erroneous foundation of Christian anti-Semitism: that the Jews killed their Christ.

When he left school, he became a teacher; and not a very good one by all accounts. He married and had two sons and looked set to live the life of a drudge, until an angry Bosnian took a potshot at an Austrian nobleman and sparked the First World War. Streicher fought valiantly for his country, gaining both distinction and an Iron Cross, First Class, a significant German military award. During his service, he earned the rank of lieutenant and several citations for bad behavior.

After the war, Streicher returned to a Germany that was seething over its loss of the war and reeling under the weight of the reparations imposed by the victors, to say nothing of the collective trauma of losing almost an entire generation of young men. Unemployment was high, the economy in ruins, and political extremism, rampant. In 1919, Streicher became involved in the German Nationalist Protection and Defense Federation, which was formed in response to the failed German Communist revolution of 1918. The Federation was deeply anti-Semitic and blamed Jews for the loss of the war and the spread of Bolshevism.

In 1921, Streicher attended a meeting of the National Socialist German Workers (NAZI) Party; he was there to hear the Party’s leader, Adolph Hitler, speak. Hitler’s hate-filled rhetoric penetrated Streicher on a spiritual level – like Saul on the road to Damascus – compelling him to join the Nazi Party and become a devoted follower of Hitler. In 1923, his devotion was made manifest with the founding of Der Sturmer (lit: The Stormer or Attacker). The chief aim of Streicher’s weekly rag was to disseminate anti-Semitic propaganda, which demonized Jews and championed the Nazi cause: namely, the building of an Aryan super state, free of Jews and other undesirables.

In its infancy, Der Sturmer was not well received. Most sensible minded Germans, including top Nazi officials, viewed it as nothing more than the libelous ravings of a nutjob. Hitler loved it. The courts agreed with everyone else, heavily fining Streicher for his lies.

Each issue of Der Sturmer relied on contemporary iterations of age-old anti-Semitic tropes, The Blood Libel and world domination among them, mixed in with titillating, semi-pornographic drivel, and the frontpage by-line: The Jews are our misfortune.

Like all good conspiracy theorists, Streicher included a grain of truth in his articles, usually in the form of an actual person, to whom he ascribed all manner of ridiculous misdeeds; tales so ludicrous, only a reader with the mental acuity of a gnat would believe.

Unfortunately, hate begets stupidity; so, when Hitler seized power and hate-mongering became a national pastime, Der Sturmer readership rose from 10’s to 100,000’s per week, making Streicher a millionaire. The more patently ridiculous the stories, the more the Streicher’s readers gobbled them up. Hitler was in his element and read it cover to cover each week and insisted everyone else read it too. To aid this, special display cases (called Sturmerkasten) were erected in towns, so no one missed out.

So delighted was Hitler with his vulgar lackey, he made Streicher the Gauleiter (regional leader) of the Bavarian region of Franconia. Streicher used his new-found power to wicked ends, organizing a boycott of Jewish shops in 1933, and the destruction of The Great Synagogue of Nuremberg in 1938, precipitating Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass), during which 91 Jewish lives were lost, 8000 Jewish properties destroyed, and 30,000 Jewish men arrested and sent to concentration camps.

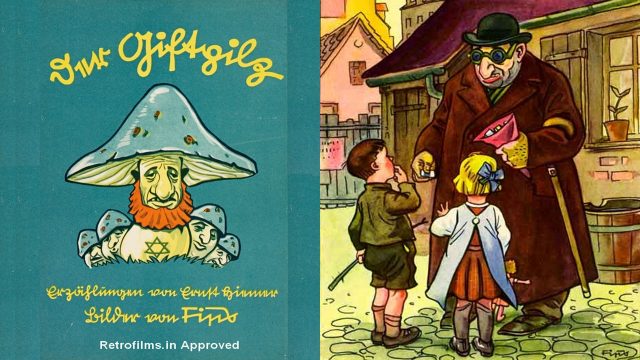

Streicher also took it upon himself to indoctrinate German youth with anti-Semitic ideology. To this end, he published three children’s books written by Ernst Hiemer and illustrated by Philipp Rupprecht (pen name Fips), Der Sturmer’s cartoonist since 1925. The most famous of these books was Der Giftpilz (“The Poisonous Mushroom”) an odious manual, warning children of the dangers of Jews.

In 1940, Streicher was dismissed from his post as Gauleiter when it came to light he’d helped himself to Jewish property during Kristallnacht. Not that Nazis were averse to theft, rather, all stolen property belonged in the coffers of the Reich. Streicher’s release from his Gauleiter duties meant he had more time to dedicate to his pathological Jew-baiting, which continued unhindered until the bitter end.

That end came in 1945, when Germany lost the war (again) and Streicher was captured by the Americans and put on trial in his hometown of Nuremberg. Having taken no part in the waging of war or the decision-making process responsible for the Holocaust, Streicher was tried as a major war criminal based solely on the things that he said (a cautionary tale for any who suppose the privilege of free speech is bulwark against consequence).

What he said was considered so odious, so incendiary, that he was convicted of crimes against humanity and sentenced to hang. His hanging went badly. Having declared his allegiance to his dead Reich, the floor beneath him gave way, but his neck did not break, so he jiggled and moaned until the life was slowly choked out of him, receiving one last kindness from humanity when his executioner pulled on his legs.

References:

Bytwerk, Randall L. (2001) Julius Streicher, Cooper Square Press, New York.

Carruthers, B. (2014) Architects of Darkness: Julius Streicher, Total Content Digital

Rebecca is a painter, collage artist and writer. Originally from New Zealand, she now lives on a little Island in the Irish Sea. She has a degree in Religious Studies and is passionate about religious history, philosophy and esoteric goings on. Her favourite research topic is peculiar religious figures; those people who, through their devotion and vision of the divine, challenged the religious establishments to which they belonged, sometimes being crushed by those establishments, other times irrevocably changing them.

You can contact her and/or find her artwork and other writing on her website rebeccaodessa.com