Albatrosses are not the prettiest birds in the world, but, when it comes to flight, they are the most majestic.

They are largest birds of the Diomedea genus, named after the Greek hero, Diomedes, the renowned warrior, and suitor of Helen, who fought at Troy (not to be confused with the Greek god, Diomedes, son of Aries, the god of war).

There are 22 known species of albatrosses, including Wandering, Royal and Laysan (meaning, wisdom). Once hunted for their feathers to use making hats, albatrosses are now a protected species; their status ranging from critically endangered to vulnerable, depending on the species.

Albatrosses have the longest wing span of any bird on the planet today, with some stretching up to 3.5 meters, which facilitates their exceptional gliding ability.

They inhabit all oceans except the North Atlantic, and feed mostly on cephalopod (squid and such), small fish and crustaceans. Although they can shallow drive, they feed mostly on the surface of the water. They are prone to follow ships, especially fishing boats, to feed on scraps of food left in the wake. They can go days without eating, but when they do find food, they gorge themselves to the point where they can’t fly, and have to sit on the water and float for a while.

Albatrosses can live up to 50 years of age, and reach sexual maturity around the age of 11. To attract and secure a mate, they engage in a complex dancing ritual, which takes them 2 or 3 mating seasons to master. The ritual involves spreading their wings, rapping their bills and braying.

Albatrosses mate for life; and, if their mate dies, they often spend the rest of their life alone. They are usually solitary when on the ocean, but return to their specific colony every two years to breed with their mate. The have and raise only one chick at a time and have the longest incubation and chick- care cycle of any other bird. The female will lay a 10cm long egg, which is then incubated for up to 11 weeks. Both the male and female birds each take turns to sit on the egg.

Once the egg has hatched, the co-parenting continues for up to 9 months, with each taking turns to care for the chick and hunt. Eventually, both parents will hunt at the same time, leaving the chick alone for increasingly longer periods of time. Albatrosses are not taught to fly by their parents, rather, they teach themselves through trial and error.

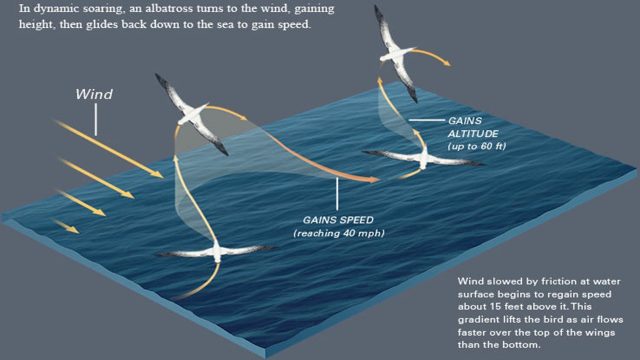

The albatross’ mastery of flight sets them apart from other birds. Optimizing wind currents close to the sea, they can soar in the air without flapping their wings for several hours at a time, reaching speeds of up to 67 miles per hour. To achieve this, they employ “dynamic soaring,” which involves climbing into the wind by tilting their wings, and then turning and gliding in a swooping fashion for up to 100metres. Although it may seem like they are simply being carried by the wind, they are in fact flying, often up to 3 times faster than the wind.

By endlessly repeating their dynamic soaring maneuver, they are able to cross vast oceans. Recent studies show they can fly up to 10,000 km in a single journey, and are known to circumnavigate the globe up to 3 times per year; with one recorded orbit taking 46 days. In this way, they can spend up to 5 years at sea at a single time. Their dynamic soaring is so efficient that they can use less energy in flight than when walking on the ground or sitting on a nest. For this reason, aerospace scientists at NASA have been studying the albatross in order to develop drone technology for use in long-range oceanic exploration.

Long before scientists became fascinated by this majestic bird, albatrosses inspired artists and poets alike. The pinnacle of such inspiration was reached in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s sublime poem, Rime of the Ancient Mariner. The poem recounts the tale of an old mariner who kills an albatross, thus dooming himself and the ship’s crew. For, according to ancient maritime lore, to kill an albatross is to court calamity (as it was believed they were the souls of drowned sailors). As punishment, the mariner is forced to wear the dead albatross around his neck. From this, comes the metaphor, “to have an albatross around one’s neck” – referring to a state of struggling with a psychological burden that feels like a curse.

Albatrosses spend the majority of their lives in flight; because of this, they have almost no natural predators. Sadly, their biggest threat today comes from humans. It is estimated that longline fishing alone kills up to 100,000 albatrosses per year and pollution of the world’s oceans is also causing a problem.

It is because of humans that albatrosses are classified as a vulnerable species. However, in a profound contradiction (typical of much of human behavior), humanity is also doing much protect these majestic birds, both in terms of protecting their breeding colonies and in changing laws pertaining to longline fishing – which is also detrimental to dolphins, sharks and sea turtles.

But that still leaves our trash. Albatrosses are prone to eating plastic, mistaking it for small sea creatures. It ruins their digestive systems and makes them feel full when they are starving. If we end up killing off a species like the albatross – not to mention countless other species of marine life, both majestic and humble – because of our trash, produced mostly from the things we don’t need to survive (pretty much everything made of plastic), then, not only will we be courting calamity, we will show ourselves to be a parasitic cancer, and by far the worst thing ever to have befallen this beautiful planet. Surely, we are, and can do, better than that!

Sources:

Rebecca is a painter, collage artist and writer. Originally from New Zealand, she now lives on a little Island in the Irish Sea. She has a degree in Religious Studies and is passionate about religious history, philosophy and esoteric goings on. Her favourite research topic is peculiar religious figures; those people who, through their devotion and vision of the divine, challenged the religious establishments to which they belonged, sometimes being crushed by those establishments, other times irrevocably changing them.

You can contact her and/or find her artwork and other writing on her website rebeccaodessa.com