2003

I’m in Israel, the Holy Land, just south of Netanya, with my wife Maria and our four kids at my friend Doron’s kitchen table. We’re eating fried Libyan potatoes and chicken thighs beneath a massive color photograph of his wife’s rear end. I suspect he’d be pleased if the image was to conjure up notions of God or beauty, but it doesn’t. To me, and excuse my cynicism, it’s just about her ass.

To make things even more challenging, Doron has this peculiar and annoying verbal tic. He can’t seem to help himself from cramming random comments like: “I’m looking to sell my brownstone on the upper west side…” “The London apartment is in need of a complete remodel…” “We’re taking out the carpet in our suite at The Herods in Eilat, replacing it with hardwood…” into normal conversations. And worse, he says these things gravely, as though he were bearing the weight of some tremendous burden.

Because later-life friendships like the one Doron and I are developing contain no shared history or experiences, ones that might help to mitigate the effects of the stupid things we all say and do, they seem to be forever resisting a slide back into stranger-hood. And as far as I’m concerned the tenuous bonds between us are already starting to fray.

After the last of the chicken thighs are eaten, my wife and I head downstairs to start packing our suitcases. My family’s been in Israel for over a month and later this evening we’re finally leaving for home. I spent much of this trip worrying about my oldest son Isaac, who suffered his first broken heart just a few days after we arrived. His girlfriend back home in LA, (bless her and her technology) snapped it in two via text. As a result, he’d been even more sullen and more reluctant then usual to go with the rest of the family on our daily drives. Drives which were admittedly, often no more than directionless excursions criss-crossing this hot and strange country in a rented minivan, in search of something I have yet to define. I was nine when I made my first trip to Israel in June of 1968, almost exactly a year after the Six Day War. Even then I was weighing the sensations, grasping for the very essence of what constitutes home.

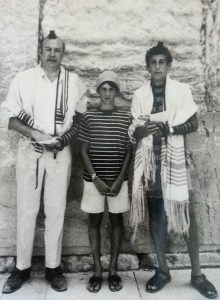

Wailing Wall (from memory)

I’m with my Dad and my brother Paul at the Wailing Wall. It’s weird to think that only a week ago I was at home watching Gilligan’s Island and looking for my Dad’s Japanese Playboys in the bottom drawer of his bedroom closet during the commercials. Now, I’m in Jerusalem, in the glaring sun beneath this gigantic wall of stone. When I’m sure no one’s looking, I put both hands on the wall, and then, I touch my forehead to it. The stones are colder than you’d think they’d be in all this heat.

For reasons I don’t understand I start to cry. I’d be embarrassed if my brother or my dad saw me like this, so I pretend that I’m praying, (as if that isn’t embarrassing enough). I wonder though, am I crying because you’re supposed to cry here? If the Rabbis from the Talmud Torah had shown me pictures of some random bridge in Saint Paul from the time I was in nursery school, would I have cried at that too?

For reasons I don’t understand I start to cry. I’d be embarrassed if my brother or my dad saw me like this, so I pretend that I’m praying, (as if that isn’t embarrassing enough). I wonder though, am I crying because you’re supposed to cry here? If the Rabbis from the Talmud Torah had shown me pictures of some random bridge in Saint Paul from the time I was in nursery school, would I have cried at that too?

Sometimes, I actually cry for God. I don’t picture God as an old bearded guy or anything. I just think of Him as… I donno, maybe like a baby. A really powerful but helpless little baby who’s always lonely because he’s been left in charge of everything; every snowflake and every whale, every single drop of water in the ocean.

Who’s He got as a friend? He has all the power in the world but He can’t use it. He’s just gotta sit there and watch all the stupid stuff we do. I usually don’t think about God when I’m watching TV or eating. It happens mostly when I’m alone in my bed, with the lights out and the crickets making noise outside my window. It also happens a lot when I have a fever and all the regular stuff I think about disappears.

When I look up at the wall again, I see some bird’s nests and a million pieces of paper with people’s prayers in them, all stuffed into the cracks between the stones. Everyone who comes here wants God’s attention. I’ll bet He loves all the notes. They probably make Him feel like someone cares about all the cool stuff He does.

Saint Louis Park

I was born a Jew in Saint Louis Park, Minnesota, a medium-sized suburb just fifteen miles west of Minneapolis. Growing up Jewish wasn’t a good or a bad thing anymore than growing up with snow was good or bad. It just was. But because we Jews were so few, being one made us all feel different. It wasn’t a difference we’d asked for or earned either. It too, just was. Becoming somewhat Jew-centric was natural for us. We stayed close to one another, close to our causes and to our history. It was an instinctive reaction to being different and few.

Given that Israel is the Jewish Homeland, discussions having to do with the Jewish State were a familiar part of my upbringing. Words like “Masada”, “Moshe Dayan”, “David Ben-Gurion” and “Tel Aviv” stole their way into our family’s daily conversations. And since Israeli politics always engenders strident opinions and heartfelt emotions, they were spoken in emphatic tones by know-it-alls and know-nothings, alike.

My friends and I went to Jewish school five days a week after public school, we all spoke at least some Hebrew, and, though I can’t speak for all my Jewish friends, by some osmotic process, I found that by the time I was nine, many of us had developed a powerful affinity for a land and a people that we hardly knew. Even though I loved (and still do love Minnesota), once I actually visited Israel in that summer of 1968, I found it to be a place which made me understand that a sense of belonging, no matter how intently I conspired to pass as Nordic, was something that life in Minnesota could never fully provide me with.

***

I continue packing my suitcase, trying to cram in my karate gi, which I should mention is how I came to know Doron in the first place. We met last year at a karate dojo next to a Kosher Nathan’s hot dog restaurant in west LA, where I used to train three or four times a week with my wife. She and I eventually got our black belts from the Karate master Hidetaka Nishiyama, but we quit within the year like most people who get their black belts. Doron was simultaneously practicing his kata and reading emails off his Blackberry the first time I saw him. I thought he looked vaguely like a tapir.

After finally getting my suitcase to close, I notice there are three unread messages on my cell phone. I sit down to listen. The first one’s from my brother in law Russell in New Jersey.

“Get a hold of me as soon as you get this.”

The next message is from him as well.

“Call me as soon as possible.”

The last message comes from someone at El Al airlines.

Call your family, dere’z been an emergency.”

Holy shit, it’s happening again. It’s another nightmare phone-scenario. I’ve got this wretched feeling in my gut like when my Dad died in 1984. Moments are elongating, stretching. I feel myself receding into individual pockets of time, each one a second or a lifetime, (who the fuck knows which is which?) I stare off at another of Doron’s photos. This one, of a young Bedouin girl with a clay jug of water balanced on her head. Minutes are moving so slowly it feels like I’ve got all the time in the world, and I’m thinking, “I wonder where is this girl is going.”

Doron sees my expression; he knows something isn’t right. Like some annoying sensei, he tells me to breathe slowly and to think only about my kata –as if all the answers I need at this moment are to be found in karate. As he continues to speak, his voice turns into a distant buzzing. My ears become extra sensitive. I can hear the hands of an electric clock as they move in stutter-step on the edge of the counter, and I can hear the clink of melting ice falling to the bottom of Doron’s water glass.

Emergency…? Oh shit, who is it this time?

My Mom is getting older but she’s in good health. Shit, that would sting. Maybe it’s my Uncle Mark. He’s in his early eighties and deep into Alzheimer’s. No, it couldn’t be Uncle Mark, I mean; I love the guy, but El Al airlines leaving messages for him? My Brother Paul? He rides his bike to work everyday, even when it’s raining. That would be worth a call from EL AL.

I dial New Jersey. It’s just after four in the morning and my sister Nina answers,

“There was an accident. An old woman fell asleep at the wheel.” And then:

“Susie’s dead. They tried to cut her out with the Jaws of Life.” I go into zombie-emergency mode just like I did when I heard my Dad died.

“Okay. I’ll get back to ya,” I say. I say this just like you might say, “I’ll get back to ya about that color for the sofa in the living room.”

ZEM, or Zombie-emergency-mode is good. It’s helpful when you need to be calm and get things done, helpful because I need to get our family to Minneapolis instead of home, to LA. ZEM is also helpful because there will be a funeral to get to, luggage to be shipped, phone calls to be made. You can’t do all that when you’re feeling too many emotions.

“What, What is it?” Maria needs to know, and so I repeat what I’d just heard. “There was an accident…” she’s bracing herself on the tile floor. I look up at the Bedouin girl with the jug on her head as I’m speaking. “It was somewhere in Wisconsin.” She holds her breath.

“Susie’s dead,” I say in my calmest voice.

And Maria explodes into weeping like a piece of tissue paper bursting into flame. I look up at the photo of the Bedouin girl again. “Strange,” I think, “There were some camels loping behind her that I hadn’t noticed before.”

***

My sister is gone. Susie, my little sister, the one who quietly distinguished herself as the only person I’ve ever met who took no joy whatsoever in one of the most joy-filled of all human endeavors: the ripping to shreds of their fellow human beings in their absence. Susie literally never said a bad word about anyone. I don’t mean to idealize her, but she clearly had different wiring than the rest of my family.

She and I were close, close in age and close to each other, especially when my older siblings, Nina and Paul went off into the world. When we were little, maybe four and five years old, Susie and I used to play a game called Unborn Duckies. I’m pretty sure it was my invention. It consisted of us going under the covers of our parent’s bed and crawling down to the foot of it, where it was dark and hard to breathe. We’d stay there for long stretches in wordless communion.

The game itself was just a pretense. Even as a young kid it would have been embarrassing to me to be caught trying to create the kind of intimacy one can experience only by being born together like twins. Even then, as a child, I needed to feel the confirmation of an endless, boundless fealty to another human being. Now I’m sad to say, there is just one duck.

There were four of us kids who grew up in a small house on Rhode Island Avenue, three bedrooms upstairs, a kitchen with a screen door, which led to a thin strip of lawn that was hard-pressed to be considered a backyard. Our basement was semi-finished. It boasted a laundry room, the walls of which, in a fit of my mom’s sudden artistic ambition, were covered by a decoupage collage of cut-out images from Look magazine: The first moon landing, JFK with his hand on the Bible, Gloria Steinem, Muhammad Ali standing over Sonny Liston, and several works by Toulouse Lautrec and Marc Chagall. There were two huge cement tubs in the laundry room, one of them was used to shampoo our various dogs through the years, and the other was used for my mom’s delicate undergarments, which never failed to attract my youthful attentions.

In the semi-finished basement itself, there was a built-in bar, replete with a hand-cranked ice crusher. Neither the bar nor the ice crusher was used much, except by me. Whenever I needed injured soldiers for a game of “army,” I’d take an unfortunate plastic figurine and run it through the ice crusher. A few quick cranks on the handle, and that little guy became a perfect green plastic replica of someone who’d just been blown to bits by a land mine.

It’s important to note that I come from a very funny family. Humor was the rhythm and the music of our conversations. We liked to juxtapose. We were preternaturally gifted in the art of forcing of one desperate idea on top of another. People who are humorous, whether they’re purveyors of humor or consumers, (it makes no difference,) are people attuned to the substrata of events. They are aware of pulses and rhythms that go undetected by the average person.

While everyone in my family was naturally funny, I thought of Susie as the least so. She seemed to be listening to the rest of the family’s conversations from the sidelines. She was hardly ever a contributor to our family humor and, because I never remember her laughing much, I didn’t believe she understood why, when my dad blamed his resonant dinner table belches or farts on our dog Pappo, it was extremely funny.

When Susie was seventeen she got a job working at the Minnesota Renaissance fair. These summertime gatherings began in the 1970’s. They were essentially reenactments of the debauchery, the frivolity, the hedonisms of Europe in the fifteen hundreds. Instead of cotton candy and Tilt-a-whirls, you’d find turkey legs, lutes, bawdy women in bosomy corsets, would-be actors reciting Shakespeare ad naseum, along with assorted jugglers, hoop throwers and horsemen. It was a new take on the regular old state fair, minus the deep fried Milky Way bars and the Midway rides.

Of course I was concerned about Susie, what could she possibly be doing in a place like that? It turned out to be even worse then I’d feared. Impossible for me (or anyone in our family) to believe, but my little sister, the un-funny one, was hired to do improv comedy sketches, sort of a strolling sexy minstrel of the humorous bent. Knowing first hand that my sister was not only not funny, but that she had no ability whatsoever to go up to complete strangers and engage them in merry-making, I feared for her. Someone in Renaissance fair HR must have been doing some serious drugs. Turkey leg in hand, I went with my girlfriend Janet to look for her. She could have been anywhere, roaming the twenty plus acres of the forth-annual Minnesota Renaissance fair.

The air was redolent with fried foods and smoke from burning hardwood. The blacksmith’s hammers were clanging, the pigs in the dusty pen were braying, and the medieval choral music rose into the sky. Out ahead, I saw a crowd of about 100 people assembled near a fence at the edge of the horse stables. Every so often a sound erupted from the crowd, a deep echoing laughter. A lone figure was standing just in front of the crowd, gesturing here and there, dancing back and forth, and all the while talking non-stop. The crowd appeared to growing, minute by minute.

When I was close enough to recognize that the person holding the people in her sway was Susie, I stood back and watched, incredulous. She wasn’t just funny; she was fucking hilarious. She had real power as an entertainer. More than the way she worked that crowd, what struck me most was how wrong I’d been about her, how I’d formed all these false assumptions about her (as had everyone else) and how she’d quietly tricked us into believing she was something entirely other than who she really was.

***

I won’t bore you with how difficult it was to travel by taxi to Tel Aviv in a state of compartmentalized anguish, or how hard it was to have to explain to the pretty young woman at the El AL ticket counter that I needed to change our entire family’s tickets to route from Ben Gurion to Minneapolis instead of LAX less than eight hours before our flight is scheduled to depart because my sister had just died.

The taxi ride back from Tel Aviv to Doron’s house was perfectly quiet. Because I’d numbly told him all about it, the Moroccan born driver I’d hired to drive me to Tel Aviv knew enough not to say a word, knew enough just to allow the silence to wash over us as the sun began to set in a hazy sky over the Mediterranean.

Twenty-five hours later our family is the last to arrive in Minneapolis. Everyone’s been waiting for us. My brother Paul and I exchange the same unbelieving glances we’d shared the night my dad died. The kind where every word and every action is on the edge of being the most hilarious or the most tragic. Hilarious, because all this tragic stuff happened so close to home and the ridiculous details of daily life, tragic because the dark humor of it made us feel so far away.

1984

Sometime back in November of 1984, maybe it was when we were shoveling dirt on my dad’s casket and the only sound was the dull thud of earth on the drum-like pine box, I looked over at my brother and said something inane.

“I love the look of the new Hunts ketchup bottle.”

The wonder of juxtaposition is that it makes everything so hilarious. That’s one of the microscopic perks of tragedy I suppose.

(A memory of the morning we buried my dad)

It’s all grey. The sky, the dirty snow. Even our skin’s turned grey. There’s a billboard advertising Coca Cola just over the cemetery fence. The red and white of Coke used to make me feel safe, comforted by the sheer power of its ordinariness. Now it’s clear that shit’s nothing but sugar water and caramel coloring.

The chapel at the cemetery is overflowing with people. Most of them have to stand outside. Someone turns on a cassette deck with the song I wrote for my dad on his last Father’s Day. Everyone cries.

I heard the ground was frozen so hard this morning that the backhoe could barely dig the grave. I look up at my brother as we shovel the dirt on our father’s casket. We can’t help from laughing. What we’re doing is so absurd. So impossibly absurd.

***

My sister Susie, her husband Peter, and two of their kids had been driving home from Camp Ramah in their Toyota mini van. It was visitor’s day up in scenic Conover, Wisconsin; they’d driven up to see Michelle, Susie’s oldest. I don’t know what went on at camp that afternoon. I never asked. Maybe some skit with a Jewish theme, someone playing a guitar, the sound of young people singing Oasis or some David Broza covers on an acoustic guitar near a lake… I don’t know exactly what happened at the site of the accident either. I never asked. Here’s what I see in my mind’s eye based on the little I was told:

An elderly woman coming down a two lane highway in a Cadillac, trees on either side, a Barney VHS playing in my sister’s mini van, Christian radio in the Caddy, eyelids slowly slipping down over tired old-eyes, a dream of a firstborn son from long ago, hands letting go of the wheel, slipping to knees covered by a rayon dress from Wal-Mart and then an awful crash –I suppose.

Susie had spoken some words to Peter and her girls from the upside-down mini van before she died. Perhaps she whispered goodbye; I’m not sure. I never asked. She was stuck in the wreckage as the rest of her family were taken to a nearby hospital and treated for minor injuries. Susie bled too much on the inside before they could cut her out with the Jaws of Life and place her in the medivac. Paul and my Mom saw Susie in the hospital on a gurney covered with blood. She was DOA. I don’t know what else they saw. I never asked. By the way, if you ever accidentally kill someone in a car accident, I suggest you study this letter we got from the elderly lady who killed Susie. It’s good.

I cannot find adequate words to express my sorrow for the loss of your mother. We lost our youngest son Vernon at the age of seventeen shortly before his high school graduation in a gun accident. I only share this with you to let you know that I have some idea of the horrible pain and loss you are going through.

I wish your mother’s life would have been spared and mine taken instead. I live with that anguish everyday. I would never intentionally hurt anyone. I simply do not know what happened the day of the accident. I will continue to ask for God’s forgiveness and ask him to watch over you and your family. I pray that only good things happen to you. I hope that someday you will find it in your heart to forgive me. I’m truly sorry for your loss and pain.

Somehow I always knew Susie would be the first of my siblings to die. I used to think it would have been breast cancer. I used to imagine all of us suffering her suffering, just like we did with my Dad.

My younger sister was never strongly rooted in the world. I don’t say this as a criticism of her; it’s not a comment about weakness, not at all. She wasn’t the least bit weak. You see; if there were a criticism to be made, I’d direct it towards God. He didn’t make her well enough. You could see right through Susie’s skin. It was like the animal part of her, the very stuff of her was too thin. It was like the shock of suddenly seeing naked flesh through a tear in a blouse, that’s how easily you could see her spirit. She seemed vulnerable too, like something more than human, or something too kind to be human. Like I said, I don’t think God made her very well.

Shivah

There are already plates of food piling up on the counter in my Mom’s kitchen before the funeral. Mostly these:

Bagels, lox, dill pickles, Spanish olives stuffed with pimentos, pickled herring, whitefish, gefilte fish, red and white horseradish, red onions, cut fruit, rye bread, blintzes, banana bread (some with chocolate chips, some with walnuts) and several kinds of cream cheese.

What strikes me as odd is how these foods, present in every Ashkenazi Jewish house of mourning, are the very same foods (down to the Spanish olives and the whitefish) that you’ll find at every joyous celebration, every Bris and every baby naming. They are neither foods of joy nor of sorrow but ethnic foods that declare at times of profound change, that we are a people connected to a tradition and a past. We are the people of the unwavering Rock. The Rock of Israel and neither the deepest tragedy nor the most intoxicating happiness can wrest us from our past or our destiny. I put three pieces of gefilte fish on a paper plate, slather them in blood red horseradish and wolf them down.

Minneapolis (Hodroff & Sons Mortuary)

A sign reads: CAUTION! Refrigeration Room. There are chemicals present which are known to the state of Minnesota to cause birth defects.

I’m sitting on a musty couch in the basement of Hodroff & Sons Mortuary listening to the low growl of the massive refrigerator’s compressor switching on and off. A month from today my younger sister Susie would be turning forty-one had she not died three days ago. I’m reading psalms as tradition dictates, within feet of her body as it cools behind a huge metal door. Some friends of mine come to sit with me and I don’t feel particularly sad. It’s as if the “I” of me has gone away. The person with my face and my name, the person sitting-in for me will talk and make some wry comments until I return.

After an hour or so, my friends leave and I feel an urgent sense of obligation, a need to clean something or serve food to someone. But no one’s here; its just me, Susie’s body, and that hovering spirit of hers that used to peek out from her too-thin skin. I feel like I should open the metal door and sit in the cold beside her corpse, maybe hold her hand, speak some soothing words, but I’m afraid, afraid to sit next to the dead. Afraid to see and to confirm what needs no confirmation. Instead I sit on the couch bemoaning both my loss and my lack of bravery.

The next morning at the funeral I can’t cry. I float through the service at a remove, watching as Susie’s daughters, bruised and bandaged from the accident, are led into a black Lincoln and driven to the cemetery. At Susie’s open grave, the bereaved are enjoined to complete the burial ritual by shoveling dirt on the casket. It’s a mitzvah and it’s better than letting the goyishe workers finish the job with just a few clattering scoopfuls from the Caterpillar.

It’s my turn to take the shovel and, though I haven’t slept in days, I feel suddenly strong. I climb to the top of the dirt pile, kick the blade of the shovel with my boot heel and drop the dry soil over the top of the casket. I can hear birds taking to flight over the crosstown highway and I feel the sun on my neck and shoulders. I imagine I am covering my sister with a warm blanket, tucking her into bed one last time, as though this final act might atone for all the times I failed her.

I think about Unborn Duckies. And at last, I start to sob. The tears, which hadn’t come until now, are precious to me. I listen to the thump of each rocky clod of earth as they land on her casket. I think about rhythm and drums, history, and the missing face of God. I feel unfettered, mystic. I feel light and exquisitely primitive.

As I’m shoveling, a hand gently touches my shoulder. It’s the Rabbi from congregation Beth Emet and, loud enough for everyone to hear, he stage-whispers, “Peter, why don’t you give someone else a chance?” It’s a solemn moment and yet, I can’t help wanting to raise the shovel high above my head and come down hard with the blunt edge on the Rabbi’s neck. Instead, I step away from the grave and give the shovel to another mourner.

There are people who have been made wise through grief and time. They learned through their painful lessons, the value of silence. For others, the allure of a performance is just too powerful. I look back at the Rabbi from Temple Beth Emet and smile as I see him, away off in the distance. But now, out among the throng of mourners, I see my Mother’s best friend Carolyn. Carolyn is one of the wisest people I know. Her husband, Burton died a few years ago and immediately after his funeral, at the shivah house to be precise, her twenty five year old son, Marty, dropped dead of a brain aneurism. My Mom got a call from Carolyn the day it happened. “Beverly,” she said, “Martin died”. “No Carolyn, my Mom said with real solemnity and real pity, “Marty didn’t die, it was Burton.” But my mom was wrong, Marty did die, on the day of his own Father’s funeral. Trust me, this woman, Carolyn, has mastered the art of being there without ever having to say a word.

Two months after the funeral, I’m back in Minneapolis and I’m sitting with my mother in her kitchen. She tells me there’s a dead muskrat in the pond at the edge of her lawn. “What should I do?” she asks.

I walk down to the pond as she waits inside. From a distance the pond looks like a putting green, the algae so thick it’s become a carpet on the surface of the water from too much fertilizer sluicing off the lawns encircling the faux lakefront. Just under a sweeping elm I saw what at first looked like a large grey-black stone. It turned out to be a muskrat that had died face down in the shallow water. All that was exposed was its huge smooth backside.

Normally I don’t do muskrat removal. Normally, I’d call a professional, but things are far from normal. As I look back from the pond at my Mother standing in front of a large picture window two troubling questions arise: Exactly what is the essential difference between me and the guys you call to haul away the stinking carcass of a rotting muskrat and why is it assumed that I’d have to call on one of them to do the job?

Maybe, it’s my Mother’s intense sadness or maybe it was having recently been in Israel (where Jewish men haven’t yet become entirely feminized) that compels me to march back through the evergreen hedges, back through the yard to grab a three pronged hoe and a snow shovel off the peg-board on the wall of her garage.

At the pond I don’t flinch as the hoe bites into the rib cage of the muskrat with a dull watery sound. I drag the bulk of it and the entrails that have mixed with the gurgling algae towards me. Then I lift the entire mess with the snow shovel into a double-thick garbage bag. I’m struck by how truly free of sin I feel at just the moment I twist the top shut with the red vinyl cord. I see my mother. She’s standing in her living room. Standing alone. Watching me from her large picture window.

Peter Himmelman is a Grammy and Emmy nominated rock and roll musician, visual artist, author, film composer, and speaker. Peter’s new book, Let Me Out (Unlock your creative mind and bring your ideas to life) is available here.