Purim, with its happy ending, Jews appropriately ascendant, ensconced in power, and safe from harm, sounds pretty good, especially this year, with increasing anti-Semitism, Israel at war, and hostages still in brutal captivity You might say that this is one of those years when we need Purim the most.

Of course, there is the other part of the Purim story — the part in which Jews straddle the line between justice and revenge, in which stubborn ideology leads to violent confrontation and a great deal of death. So, you might also say this is one of those years when we need Purim the least.

So, which is it? Is this the year we need Purim most or least? And, of course, the answer is “Yes.” We need Purim this year, both more than ever and less than ever, and that is because the issue isn’t Purim. The issue is us. And given God’s absence from the story as recorded in The Book of Esther — the only book in the entire Hebrew Bible in which God does not appear — it is especially clear that it is a story about us. There is no putting our response on God because God isn’t there.

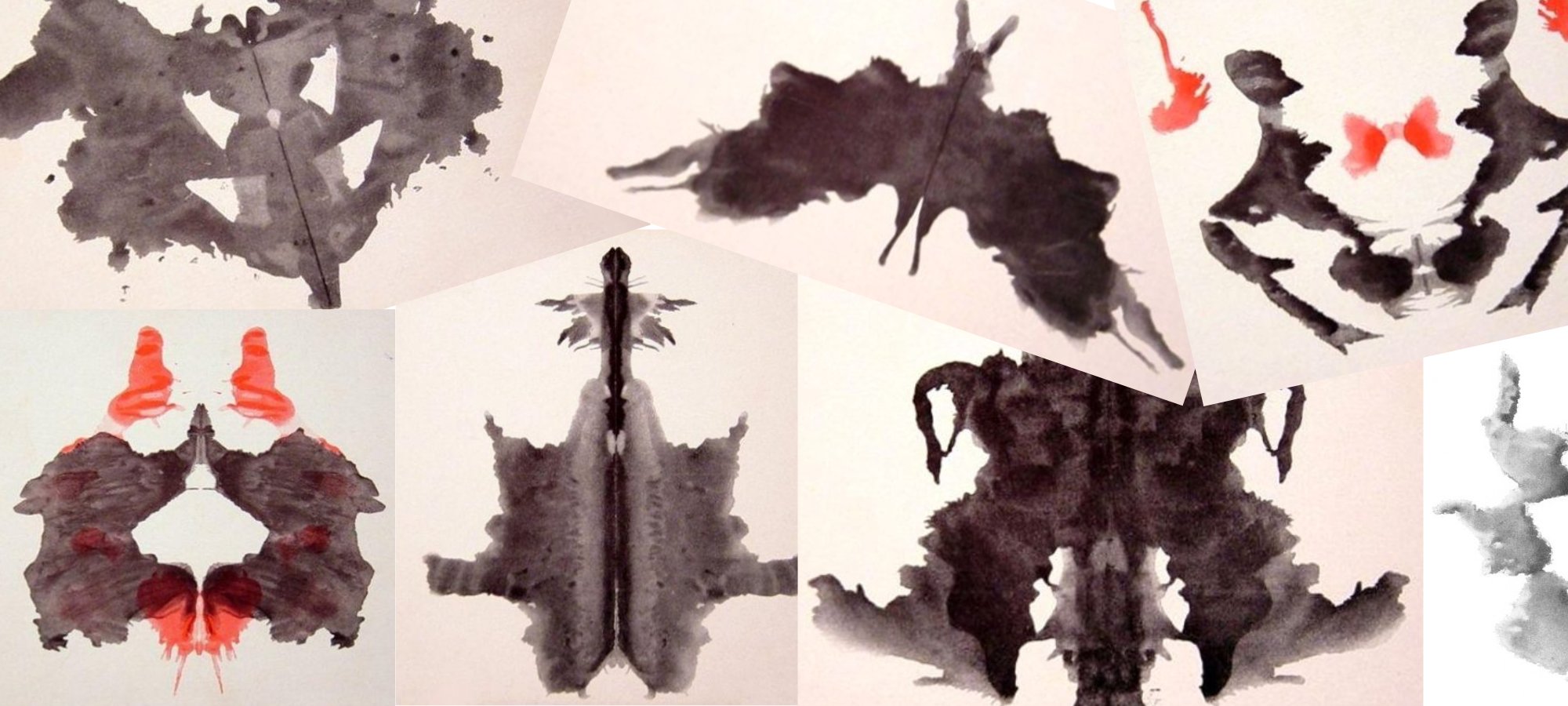

In fact, the absence of God from the Purim story is like the joke about the man who visits a psychiatrist, and she proceeds to use a Rorschach Test on her new patient. Yeah, it’s an old joke, as indicated by the use of this test, but hang in, as it is still quite timely — the joke, anyway.

The doctor shows the patient an inkblot, asking what he sees. The patient replies, “It’s a picture of a man and a woman having sex.” The doctor moves on to a second image and again asks the man what he sees. The patient replies, “That’s a picture of two men having sex.” Seeing the third picture, the patient declares, “And that is a picture of two women having sex.”

The doctor puts down the cards and says to the patient that while there is much more to explore, it is clear to her that this man is rather obsessed with sex. The man replies, “Obsessed with sex? Doctor, you’re the one showing me all the dirty pictures!”

Like the patient in the story, we tend to think that our responses to life are driven by some external controlling force – – be it God or the doctor – – or by the events and pictures that surround us. While those are definitely part of what drives us, as this joke reminds us, it is about us more than anything else. And nowhere more than the Purim story is that the case, especially with God out of the picture and the story so multi-faceted.

So, which Purim story are you feeling this year? Are you aching to celebrate the good ending to a crazy story of unfairly victimized Jews who secure their own safety in totally justified ways and cheering at the demise of those who hated Jews and sought to kill them just because they were different?

Or are you planning to lower your voice, especially as you come to the passages that tell of violence committed not against Jews but by Jews, and perhaps skipping any public feasting or celebration, given the darker sides of the Purim story?

Whether you will observe the holiday or not, whether you are Jewish or not, does one of those responses make greater sense to you as you think about the story? And what about the parallels that people draw to current events, even as the equivalences that are made between then and now are far less exact than those who often draw them believe?

Each response has its logic and its merits, as long as whatever reading or practice we choose, we can appreciate that Purim is our Rorschach test. How we understand and celebrate the story is about us more than anything or anyone else. That means that whatever path we follow, we need to appreciate that the paths not taken are often as authentic, as legitimate, and as grounded in the text as the one we have chosen. In fact, in the absence of God, our choice is all there is, which is the deeper challenge that Purim invites, or dare I say, unmasks.

To be clear, this understanding of Purim is not so new. It is as old as the Talmudic teaching found in Shabbat 88a. The story recounts how God holds Mount Sinai over the Israelites at the time of revelation and tells them that if they accept the Torah, all is well and good, but if they refuse, then God will drop the mountain on them and kill them all.

Rav Aha bar Yaakov responds that if that were the case, then the covenant at Sinai is, in fact, no covenant at all, having been made under extreme duress. No Sage challenges this claim, and instead, the texts ask how and when the covenant came into force. The answer is that it happened at Purim when we are told that the Jews “upheld and accepted” that which Mordechai told them to do. (Esther 9:27). The covenant is about us — what are we willing to accept and do, and the answers to those questions are found only when we step back — if only for a while — from God and what the text says. That is the ultimate unmasking in this holiday of hiddenness, and that is the deepest power of the holiday.

Purim is the ultimate Rorschach test, and perhaps the one thing that we can all celebrate is the opportunity to answer its questions in genuine peace and real security for all. We may understand what that means in different ways, but unless we pretend that we are God — which even God doesn’t do in this story — we can take responsibility for our chosen readings, accept the partialness of whatever reading/observance we choose, and appreciate the freedom of others to choose theirs. To that, I can say “l’chaim” with a full, if somewhat broken, heart this year.

Listed for many years in Newsweek as one of America’s “50 Most Influential Rabbis” and recognized as one of our nation’s leading “Preachers and Teachers,” by Beliefnet.com, Rabbi Brad Hirschfield serves as the President of Clal–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a training institute, think tank, and resource center nurturing religious and intellectual pluralism within the Jewish community, and the wider world, preparing people to meet the biggest challenges we face in our increasingly polarized world.

An ordained Orthodox rabbi who studied for his PhD and taught at The Jewish Theological Seminary, he has also taught the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs an ongoing seminar, and American Jewish University. Rabbi Brad regularly teaches and consults for the US Army and United States Department of Defense, religious organizations — Jewish and Christian — including United Seminary (Methodist), Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (Modern Orthodox) Luther Seminary (Lutheran), and The Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative) — civic organizations including No Labels, Odyssey Impact, and The Aspen Institute, numerous Jewish Federations, and a variety of communal and family foundations.

Hirschfield is the author and editor of numerous books, including You Don’t Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism, writes a column for Religion News Service, and appears regularly on TV and radio in outlets ranging from The Washington Post to Fox News Channel. He is also the founder of the Stand and See Fellowship, which brings hundreds of Christian religious leaders to Israel, preparing them to address the increasing polarization around Middle East issues — and really all currently polarizing issues at home and abroad — with six words, “It’s more complicated than we know.”