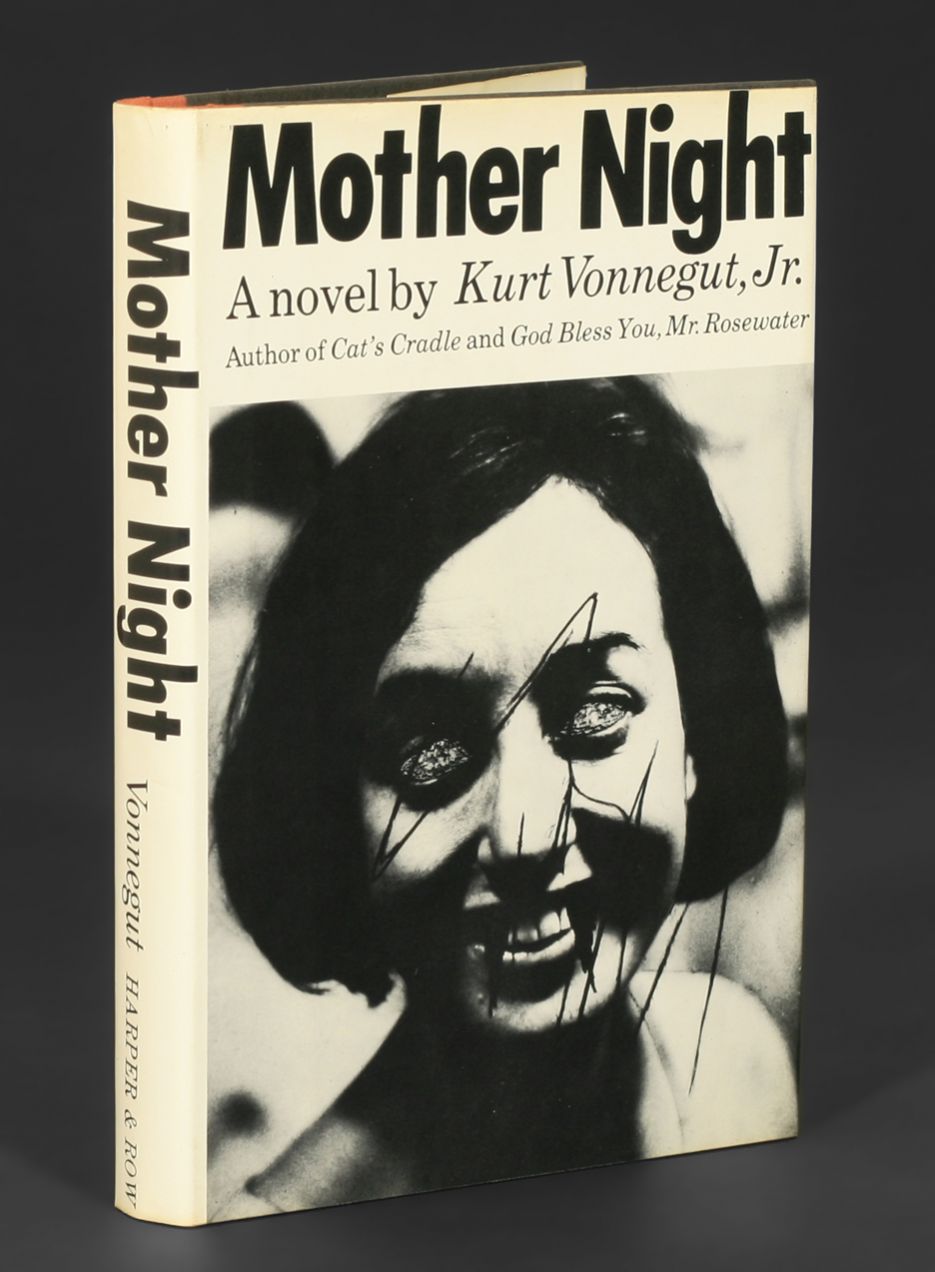

“This is the only story of mine whose moral I know,” writes Kurt Vonnegut at the beginning of his 1962 novel Mother Night. “I don’t think it’s a marvelous moral; I simply happen to know what it is: We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.”

Mother Night is the story of an American spy in Germany- Howard W. Campbell, Jr. It is framed as his memoir, written in an Israeli jail cell. Campbell is there awaiting a war crimes trial for his actions as a Nazi propagandist. In fact Campbell was a double agent who worked his way up through Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda organization, eventually broadcasting radio shows aimed at converting Americans to the Nazi cause. Unbeknownst to the Nazis, all of the apparent irrelevancies of Campbell’s speech – his deliberate pauses, his coughs or grunts – are coded transmissions to the US.

At the end of the novel, Campbell is offered an attempt at exoneration, but he turns it down and instead takes his own life. Vonnegut’s lesson seems to be that the evils Campbell took part in- even if his intentions were otherwise- have, in the end, made him guilty in his own eyes and destroyed his soul.

Vonnegut’s novel is not really about the ethical complexities of WW2. Clearly he intends, as he says, for us to draw a universal moral. As was probably clear to you as you read Vonnegut’s explicit identification of what it is, it is an intimately chilling one. Who among us is not pretending to be something they’re not out of belief that it is required, serves a larger cause, or if neither of those, at least serves our own interest and is harmless?

Vonnegut is not, I believe, talking about mere inauthenticity. He is talking about engaging in activities which do not agree with what we ourselves feel are our own core morals while telling ourselves, “This is not who I really am. I am just going along with this on the outside to get by.” Vonnegut’s message is that the separation I just described between how we act externally and who we really are is imaginary.

What Is It To Pretend?

If I search my own life for a major instance of Vonneguttian pretend, it would surely be my own participation in an ecosystem-destroying culture. Doing so clearly does not reflect my values, or at least not some of them, ones I happen to cherish. Yet I do it because of other values I hold, like security and pleasure. At the end of the day, which will matter more- my lifelong participation in industrial capitalism, or the private thoughts of my heart?

To pretend is to act in a way which is not “us”, which does not really reflect our character. Vonnegut is in effect arguing that our character in fact consists in our actions, so that this distinction is simply a fig leaf.

One could contest this to some extent, of course, and one should. Are not my conflicts, my secret desires, my dreams issued stillborn all part of my character as well?

Of course they are. Yet what Vonnegut is trying to do is to move what we might consider background in our assessment of our own character into the foreground. This is mirrored in the story about Campbell itself. A key feature of Campbell’s pretense is that what is for him foreground in his own behaviour, later shifts to become background, and vice versa. What Campbell is focused on is the grunts, coughs and pauses he needs to execute correctly according to his instructions. The actual speeches he is making are just background, yet those speeches help to incite anti-semitic and white supremacist bigotry and violence among his listeners. Much later, as his life unfolds what he had overlooked and justified becomes, in his own eyes, his chief legacy.

Campbell’s harsh self-conviction may justifiably strike us excessive, but it should also point to an even more alarming fact: he is probably more innocent than most of us. At least, in Campbell’s case, his involvement in the Nazi war machine serves a real higher cause- the American victory against it. Our motivations for heartlessly mimicking the lifestyle of late Capitalist modernity (just to pluck an example based on myself) are much less noble.

As a minor adjunct to this moral, Vonnegut later offers the observation that “When you’re dead, you’re dead.” He appears to intend this as a warning to think seriously about what we want our legacy to be and what’s at stake: what we do with what the late Mary Oliver called “our one wild and precious life.”

He also adds, “And yet another moral occurs to me now: Make love when you can. It’s good for you.”

Matthew Gindin is a journalist, educator and meditation instructor located in Vancouver, BC. He is the Pacific Correspondent for the Canadian Jewish News, writes regularly for the Forward and the Jewish Independent and has been published in Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Religion Dispatches, Kveller, Situate Magazine, and elsewhere. He writes on Medium from time to time.