“Inscribe them upon the doorposts of your house and upon your gates.”

Deuteronomy 6:9

A rabbi, a poet, and a designer walk into a bar. The rabbi orders a drink, says a bracha (blessing) over it, and then gratefully imbibes it. The poet orders a drink, savors the taste for a moment, swallows it, and then eloquently declares to the others that the libation produces an exquisite taste. Like the others, the designer orders a drink, but quickly gulps it down, spending the next hour and a half remarking on the design of the glass, and how it creates affordances for experiencing taste and gratitude.

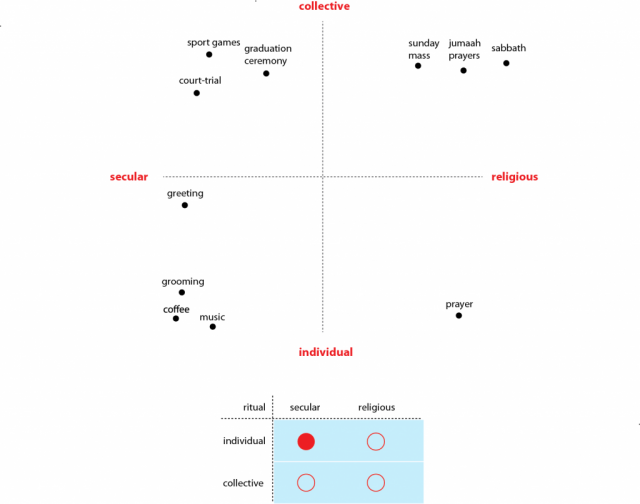

Our lives are filled with rituals. There are rituals for getting up in the morning, and there are rituals for going to bed at night. There are rituals for when we are in public, and there are rituals for when we are at home. There are rituals that orient us to the sacred, and there are rituals that structure the quotidian tasks that fill the hours of a day, and all the days of a life. Rituals allow us to exchange meaning with others. Rituals produce meaning for ourselves. Rituals give meaning to behavior, and sometimes when artfully executed, rituals can make us more aware, more mindful, and more engaged with the wonders of the world around us. A ritual is an invitation to participate.

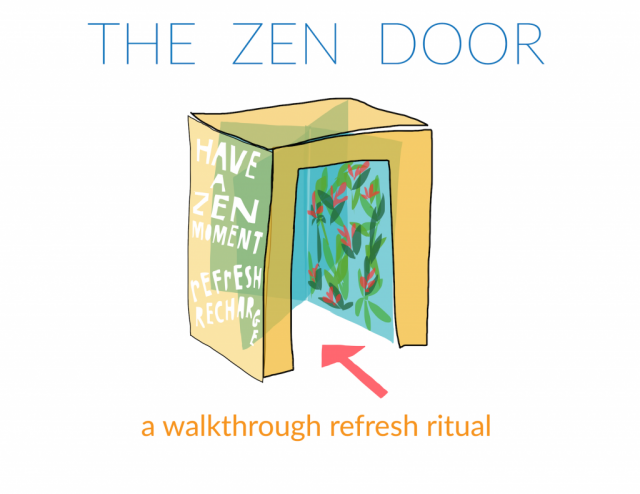

On the doorposts and gates of many Jewish homes you will find a little box, sometimes conspicuously decorated, other times quite austere: a mezuzah. It is typically placed at about shoulder level, and angled in the direction one enters the building. Within this little box, not unlike the phylacteries worn in daily prayer by pious Jews, is written in tiny Hebrew script, passages from the Torah, including the words of the Shema: “Hear O’Israel, the Lord is our G!d, the Lord is One.” It is customary for observant Jews to touch and kiss the mezuzah as they enter or leave a building. It is a act of reverence, but it also produces an awareness that one is passing from one space to another, across a threshold that marks the transition from inside to outside or from outside to inside. The mindfulness of the act gives meaning to the behavior, which might otherwise go unrecognized and ignored. A mezuzah makes one aware of the behavior of coming and going, and gives meaning to the action through attention (kavanah) to the act.

In most homes, situated just below the mezuzah, one finds another “box”, similar in size and shape to a mezuzah. It is striking that its function is not so dissimilar either. A doorbell announces the arrival of a visitor. It creates an affordance for an interaction with a guest. It is a ritual we all recognize because we do it all the time: We ring the doorbell. We wait for a pregnant moment. And we are either greeted, or we are not. It is all scripted in advance. The act of ringing a doorbell is a request, and the design of the doorbell makes that request possible. One presses the doorbell, like one might touch a mezuzah, an action takes place, and through that action we make meaning.

The built environment and the objects of our material culture create affordances not just for a particular action, and for the utility that emerges from that action, but also for the meaning that accompanies that action. Designers, perhaps not unlike poets and rabbis, have the ability to make us aware of the meaning that is given to the things we do and the objects all around us. Every object and every space we occupy are opportunities to be more aware of the world around us; to act with intention; to uncloak the monotony of habit and imbue the moments of our lives with significance.

Designers can learn a great deal from the practices of those who cultivate observance and nurture the sacred in their daily lives. They can learn much from this kind of attentive, active engagement. Attention is reality. And designers can apply these insights to rituals that not only create affordances for behavior, but create affordances for meaning as well.

At Stanford, the Ritual Design Lab is doing just that. They are applying design research methods such as human centered design, to the development of “ritual design”. They describe their project in the following way:

“Rituals can be grand, dramatic things, or they can be tiny, personal ones. Either way, rituals help people to understand the world, cope with transitions, express strong emotions, and build their own life story. Our hypothesis is that designers can use the patterns and mechanics of rituals to develop better designs?–?that are engaging for users, and that offer more meaning to them.”

The Ritual Design Lab cites anthropologist, Barbara Myerhoff, and her pioneering work in autoethnography?–?in which the researcher’s subjective experience situates them within the culture they are studying. This approach, not unlike the strategies for cultivating empathy found in human centered design, provides a perspective that allows the researcher (or designer) to transcend the limitations of being an outsider looking in on a group of people. She comments, “The most salient characteristic of ritual is its function as a frame. It is a deliberate and artificial demarcation. In ritual, a bit of behavior or interaction, an aspect of social life, a moment in time is selected, stopped, remarked upon.”

This emphasis on the role ritual plays in design can also be found in emerging discourses that examine “design futures”. Design futuring can be characterized as the speculative act of designing for a reality that has not yet come to pass. Most of us can easily identify examples of design features, such as those found in science fiction, as well as in other forms of design fiction.

“Curious Rituals” is a project by the Near Future Laboratory that explores a near future scenario where the development of new rituals is necessary for navigating a technologically saturated world… and giving meaning to it. In these examples of design fiction, storytelling becomes a particularly useful prototyping tool for exploring the relationship between meaning and behavior within speculative scenarios.

But it isn’t just designers who are hoping to gain new insights by better understanding the practices of the observant. Rabbi Charlie Schwartz and the Brandeis Design Lab are working with students to apply design strategies to hacking traditional Jewish rituals. The application of technology (e.g. Arduinos and 3D printing) to these projects has produced some especially interesting results. Rabbi Schwartz led a workshop where students were given the prompt to redesign the mezuzah.

This opened up a space for students to consider what the ritual meant in the context of their own experience. What if a mezuzah could send you, or a friend, a text message as you left a space, or could announce your arrival with a sound as you entered a room? By giving students the means by which to critique and design rituals, they are given the means to explore new possibilities for behavior and directly participate in the making of meaning.

A rabbi, a poet, and a designer walk out of a bar. The rabbi leans over to the designer and initiates a joke, which is itself a kind of ritual; “Knock knock,” the rabbi announces. The designer, without missing a beat, recognizes the script and responds with a customary, “Who’s there?” But before the punch line can be delivered, the poet breaks with convention and interrupts with a question…

“Why did you knock? Was the doorbell broken?”

Ian Gonsher is Assistant Professor of Practice in the School of Engineering and Department of Computer Science at Brown University. His teaching and research interests examine creative process as applied to interdisciplinary design practices. Recent work includes Ian’s teaching and research within the Brown Humanity Centered Robotics Initiative, and explores the ways technology might enhance our humanity, rather than rob it from us. He is also working on a translation of the Torah into light. More information about his work can be found at his website.