In our new Covid-19 era, a phone call and forwarded WhatsApp message from the chronically least developed nation in the world reminds me of the virtues of marginality. Twenty years ago, I had received a similar urgent message of concern. Then it was about my ten-year-old son, Samuel, with whom I had just visited my friends in the hinterlands of West Africa. (Two years later, with the same villager friends, my daughter Arielle and I lit candles for Hanukkah.)

My friends were greatly afraid for Sam’s safety for they had heard on the radio chilling news about America: our children go to school in the morning, and are methodically shot to death by other children. Now Faralu is asking: Are my children, wife, and mother safe from this new sickness that is raging everywhere in the world? Everywhere except – at least for now, thanks to Allah – his own nation, Niger.

Life in Niger – one of the most Muslim nations in the world by percentage – has long been one of daily struggle: anxiety from inadequate rains, little money, children dying from simple infections. Few Nigériens have running water or electricity. Beggars and blind folk still abound; flies abuzz, diarrheal infants die. The average per capita income is less than two dollars a day. But the spirit of solidarity reigns supreme and resilience is second nature. Even if Covid-19 does infiltrate, it will not threaten the social fabric as it is already starting to do in more patently “developed” societies.

I am always humbled by such expressions of concern from my materially impoverished friends, be they about the illness from an acute new virus or the chronic one that periodically prompts the young among my people to kill their schoolmates. They do not turn their back on their friends when disaster strikes; we should not, either. (Here is one great organization through which the reader may help; this is another pathway.)

Even as our bandwidth, print space, and airwaves are being colonized by coronavirus news, we should not forget our global responsibilities. Through no virtue of our own, most of us Americans happen to have been born into a prosperous nation. Not all of our co-citizens are prosperous, of course – an inequitable fact that is being made more and more obvious as coronavirus rages. Still, we won the global lottery by the luck of birthplace.

Even if the current pandemic is challenging casual cheerleaders of globalization – and I admit to having been one of them – we should not succumb to the temptation of restricting our compassion by citizenship. We are, after all, equalized by fears of infection: Black and White, Muslim and Jew, African and American. If the pandemic is a global crisis, the solution must be no less global – and personal, too.

Whether through the U.S. Armed Forces or the Peace Corps, hundreds of thousands of Americans have forged close relationships with “host country nationals” in the developing nations – most of them once literally colonized – where they have served. Even in this moment of national health crisis, we should remember our friends from abroad. I am sure they are all – like Faralu, who called again during this fast of Ramadan to convey his concern – remembering us. And I am also quite certain that they all have the equivalent of this proverb in Hausa, Faralu’s native language: “From the friend who weeps in hearing of your sorrow, hide not your own.”

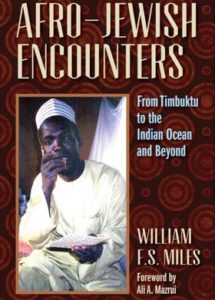

William F.S. Miles is professor of political science at Northeastern University in Boston and former Stotsky Professor of Jewish Historical and Cultural Studies there. He is author of two National Jewish Book finalists: Zion in the Desert and Jews of Nigeria. From his experiences in an Israeli Druze village, he has published School Day One: Dispatch from Another Israel, Home on Leave: An Israeli Shabbat Scene, Not Your Typical Hebrew Teacher and, with Hisham Bader z’’l, Start-up Village.