People can be difficult. We are all complex and complicated to varying degrees. We can all be prickly and pokey from time to time. But our relationships to others can also be the source of our greatest satisfactions and happiness. As psychologist Rollo May explains in his wonderfully insightful meditation on the dialectics of creativity, The Courage to Create, we crave the intimacy of others, but also seek autonomy for ourself. Our relationships are complex, because humans are complex animals, not unlike hedgehogs. The balance we find between these opposing impulses determines so much of the happiness and frustration we encounter in the relationships we have with others throughout the course of our lives.

May cites Otto Rank when he explains that, “Social courage requires the confronting of two different kinds of fear. These were beautifully described by one of the early psychoanalysts, Otto Rank. The first he calls the “life fear”. This is the fear of being abandoned, the need for dependency on someone else. It shows itself in the need to throw one’s self so completely into a relationship that one has no self with which to relate.”

May continues, “The opposite fear Rank called the “death fear”. This is the fear of being totally absorbed by the other, the fear of losing one’s self and one’s autonomy, the fear of having one’s independence taken away.”

Arthur Schopenhauer, famous for his pessimism about human character, told a similar parable. He tells a story about a group of hedgehogs (sometimes translated as porcupines), who crave the warmth generated by close, intimate proximity with other hedgehogs. But hedgehogs being hedgehogs, are prickly, and tend to poke each other as they get closer. He describes the situation in the following way:

A number of hedgehogs huddled together for warmth on a cold day in winter; but, as they began to prick one another with their quills, they were obliged to disperse. However the cold drove them together again, when just the same thing happened. At last, after many turns of huddling and dispersing, they discovered that they would be best off by remaining at a little distance from one another. In the same way the need of society drives the human hedgehogs together, only to be mutually repelled by the many prickly and disagreeable qualities of their nature.

The moderate distance which they at last discover to be the only tolerable condition of intercourse, is the code of politeness and fine manners; and those who transgress it are roughly told–in the English phrase–to keep their distance. By this arrangement the mutual need of warmth is only very moderately satisfied; but then people do not get pricked. A man who has some heat in himself prefers to remain outside, where he will neither prick other people nor get pricked himself.

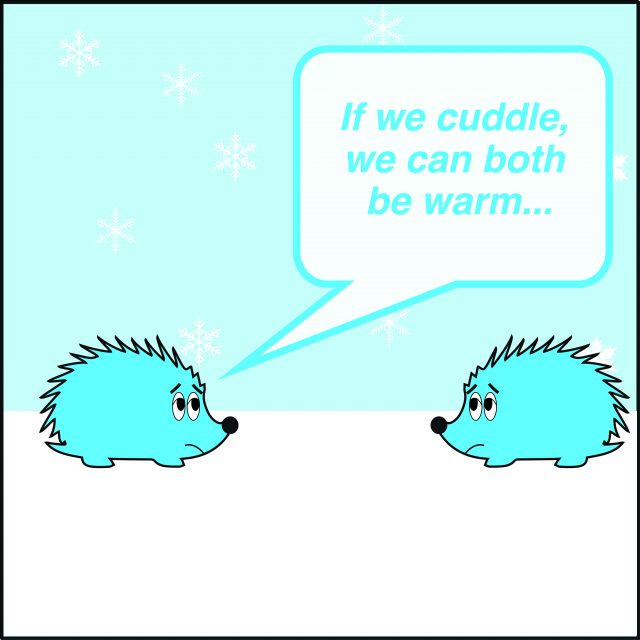

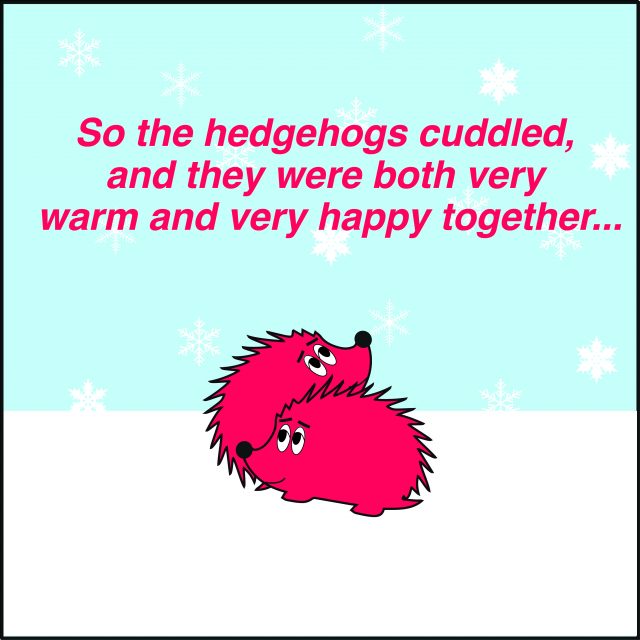

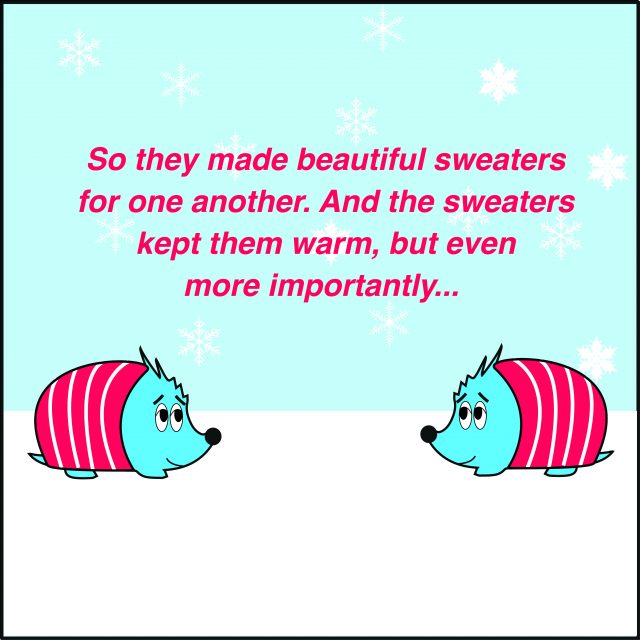

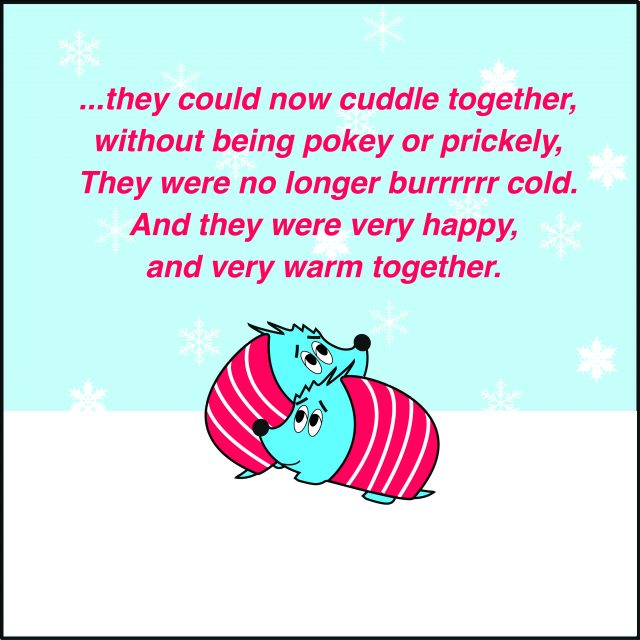

But we need not be so pessimistic about the situation we are placed in by these contradictory impulses within us. By better understanding these forces within ourselves and others, we can better play positive sum games, where the goal is to foster win/wins. The problem is even more acute for children, who need both the nurturing support of parents, while also struggling to establish their autonomy as individuals. It is a pattern they will encounter throughout their lives, so we might ask, how can we prepare children (and adults as well) to think creatively about how they balance these opposing impulses? How might we teach children to approach difficult relationships in a creative way and reframe the game into a positive sum?

The following is a visual retelling of Schopenhauer’s dilemma in the form of a children’s story, but with an optimistic addendum to Schopenhauer’s pessimism. Even in the face of prickly and pokey people, we can find ways to be warm and happy together.

Ian Gonsher is Assistant Professor of Practice in the School of Engineering and Department of Computer Science at Brown University. His teaching and research interests examine creative process as applied to interdisciplinary design practices. Recent work includes Ian’s teaching and research within the Brown Humanity Centered Robotics Initiative, and explores the ways technology might enhance our humanity, rather than rob it from us. He is also working on a translation of the Torah into light. More information about his work can be found at his website.