“We are not to simply bandage the wounds of victims beneath the wheels of injustice, we are to drive a spoke into the wheel itself.” -Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945) was a German Lutheran pastor who met the rise of the Nazi regime with heroic resistance. Arrested in 1943 by the Gestapo, Bonhoeffer was vengefully executed on April 9, 1945 as the Nazi regime was collapsing. His life and thought are a primer in courageous spiritual activism.

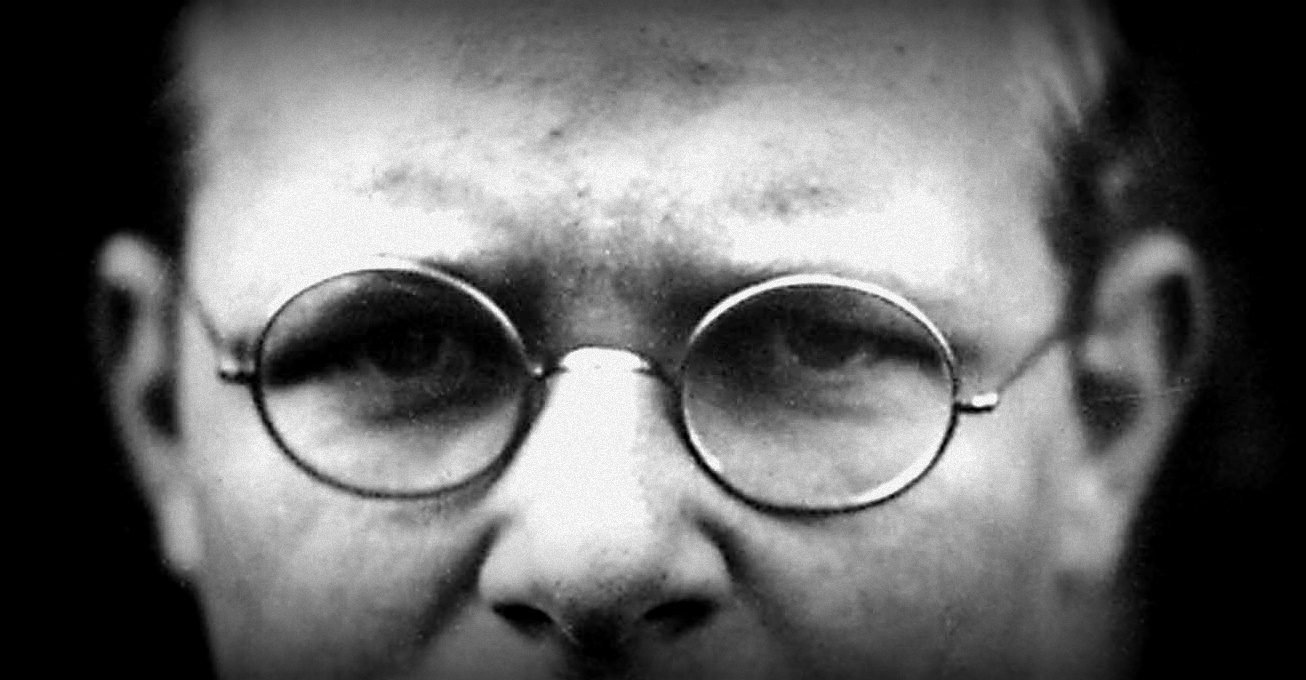

Young Bonhoeffer

Bonhoeffer grew up in a loving, aristocratic German family and entered adulthood a refined, broadly educated young man known for his brilliant, passionate mind and lust for life, as well as a not-inconsiderable tendency to pride, self-absorption and aloofness. His decision to study theology surprised everyone, but he soon distinguished himself as a student and ended his time at university by writing Sanctio Communo, a long ode to the sacred practice of community. It was an interesting choice for the aloof, aristocratic and hyper-intellectual Bonhoeffer, and one that showed the tendency to balance his own weaknesses and push into uncharted territory, which would stay with him throughout his life and soon lead him to a place where few would follow.

The young Bonhoeffer traveled throughout Italy, Spain, Libya and Morocco, writing lush travelogues rhapsodizing over the cultures, art, ritual and natural landscapes that he saw. After he took up preaching in a German ex-pat community in Barcelona, he quickly became popular with the youth of the community and became known for his lyrical, intense sermons.

“Restlessness is the characteristic distinguishing human beings from animals”, he said in one. “Restlessness is the root of every spirit that lifts itself toward morality; restlessness is… the most profound meaning and lifeblood of all religion. Restlessness- not in any transitory human sense, in which all we find is nervousness and impatience- no, restlessness in the direction of the eternal….pointing towards the infinite.”

Despite Bonhoeffer’s lifelong desire for “eternity,” he also affirmed that in faith, “our gaze opens to the fullness of divine life in this world.” He expressed his wish “to abide with those who, realizing they have no “ultimate escape from earthly tasks and difficulties into the eternal, drink the earthly cup to the dregs.” This earnest, passionate theologian, who combined a transcendent longing with an equally strong desire for creative piety in the world, would soon have his life changed by two things. The first was a trip to America. The second was the descent of darkness over Europe.

Bonhoeffer in America

While in America, Bonhoeffer studied at the liberal, social justice oriented Union Theological Seminary under Reinhold Niebuhr and other luminaries of the golden age of left-wing Protestant social justice activism. The emphasis on social justice at Union would help shape Bonhoeffer’s thought for the rest of his life, but the most profound influence on him was his near-obsessive immersion in the African American Church and the problem of race relations in the US.

Bonhoeffer, who said that he had encountered the truest expression of Christianity in the African American churches, attended the largest African American church in Harlem for six months, toured the American south, and read every book on the plight of African Americans he could get his hands on. His unflinching study of injustice towards African-Americans would train him to see the state and the world in new ways.

Bonhoeffer also immersed himself in organizations fighting for the rights of immigrants, women, and the poor led by American liberal protestants, including the early ACLU. Upon return to Berlin in 1931 he told his brother that Germany “needed an ACLU of its own.” If Bonhoeffer learned theology in Germany, he learned a new intensity of the application of Biblical ethics in the world in America.

The Fight Begins

Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany in January 1933, and president a year and a half later. His opposition in the Church soon included theologian Karl Barth, pastor Martin Niemoller, and the young Bonhoeffer (27 at the time). Barth was deported back to Sweden by the Nazis and Niemoller, who is the source of the famous quote, “First they came for the Jews…..,” spent the war in concentration camps but survived. Niemoller, Barth and Bonhoeffer were key figures in the creation of the “Confessing Church,” an alternative to the state Church (reichskirche) which Hitler soon took over and re-made in his image.

Bonhoeffer believed it was the role of the church to speak for those who could not speak. To fight unjust practices in the Church was right, but to allow them to exist outside the church would be evil. So it was with the persecution of Jews by the Nazi state. Bonhoeffer preached a fierce public opposition to the policies of the Nazis. “Only he who cries out for the Jews may sing Gregorian chants,” he said.

Hans-Werner Jensen, a friend of Bonhoeffer, wrote that Bonhoeffer’s awareness of what the Jews were going through immediately following Kristallnacht caused him to be “driven by a great inner restlessness, a holy anger.”

Bonhoeffer famously enumerated three possible stances people of faith can take towards the state. The first is to question the state regarding its actions and their legitimacy–to help the state be the state. The second way was, if needed, “to aid the victims of state action.” If things progress to the extreme point that the state no longer stands for order and justice, and will not allow people of faith to act according to their conscience, then the obligation of people of faith lay in toppling the state itself, in “driving a spoke into the wheel of injustice.” As Bonhoeffer said, “If you board the wrong train it is no use running along the corridor in the opposite direction.”

During the late 1930s, Bonhoeffer was teaching in an underground seminary due to the government banning him from teaching openly. After the seminary was discovered and closed, the Confessing Church became increasingly timid, and words proved increasingly ineffective. Bonhoeffer had tried to oppose the Nazis through religious action and moral persuasion, but soon he would take on more radical tactics. He signed up with the German secret service in order to be a double agent, through which he helped Jews escape Germany. Bonhoeffer also became a part of a plot to overthrow, and later, to assassinate, Hitler. During this period, Bonhoeffer became increasingly alone, living a secretive fight against the Nazis from within a horrific police state. His friends report that he frequently said, “The only fight which is lost is the one we give up.”

Eventually Bonhoeffer’s resistance efforts were discovered. On an April afternoon in 1943, two men arrived in a black Mercedes, put Bonhoeffer in the car, and drove him to Tegel prison. Eventually he was transferred from Tegel to Buchenwald and then to the extermination camp at Flossenbürg. On April 9, 1945, one month before Germany surrendered, he was hanged with six other resisters.

“Through the half-open door in one room of the huts I saw Pastor Bonhoeffer, before taking off his prison garb, kneeling on the floor praying fervently to his God,” wrote the camp doctor years later. “I was most deeply moved by the way this lovable man prayed, so devout and so certain that God heard his prayer. At the place of execution, he again said a short prayer and then climbed the steps to the gallows, brave and composed.”

Bonhoeffer’s God was a God who suffered in the world, the God of Isaiah and Abraham Joshua Heschel. To be a godly person was to be willing to suffer for divine values like peace, justice, truth and compassion. Suffering is not popular in our comfortable North American world, in a culture designed to try to avoid it at all costs. Yet for Bonhoeffer, solidarity with the suffering was solidarity with God, who suffers along with them.

Images of willful suffering have begun to bubble up more frequently into our mass consciousness, from the heroic self-sacrifice of the rebels in Rogue One to the hero’s brutal, but redemptive self-abnegation for his daughter in Logan, that most adult of superhero movies. On some level, it seems, we know that we may be called to suffering and sacrifice in the years to come to defend what we consider divine values, and, in that, the memory of Bonhoeffer’s courage can walk with us and ask us if we have gone far enough.

Matthew Gindin is a journalist, educator and meditation instructor located in Vancouver, BC. He is the Pacific Correspondent for the Canadian Jewish News, writes regularly for the Forward and the Jewish Independent and has been published in Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Religion Dispatches, Kveller, Situate Magazine, and elsewhere. He writes on Medium from time to time.