Benjamin Franklin’s famous autobiography includes the description of a character improvement method that he invented in his 20s to help him break his bad habits and acquire better ones.

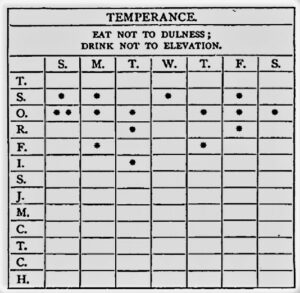

The method centers on 13 behavioral traits (temperance, silence, order, resolution, frugality, industry, sincerity, justice, moderation, cleanliness, tranquility, chastity, and humility), to each of which, in succession, is allotted a week of special attention and reflection. Progress and setbacks in mastering these behavioral traits — or virtues — are recorded on a grid chart having the seven days of the week running horizontally and the 13 traits running vertically. After 13 weeks, the cycle begins again so that over the course of a year, each virtue receives four full weeks of focus.

Though he never succeeded in fully altering his habits using this technique, later in life, Franklin reflected: “I was by the Endeavour a better and a happier Man than I otherwise should have been, if I had not attempted it.”

A notable feature of Franklin’s invention is that it was intentionally designed to be compatible with different faiths. As Franklin, whose own religious beliefs may be described as Deistic, explained: “Being fully persuaded of the Utility and Excellency of my Method, and that it might be serviceable to People in all Religions, and intending some time or other to publish it, I would not have any thing in it that should prejudice any one of any Sect against it.”

Publishing his method as a book was part of what he described as “a great and extensive Project.” Franklin envisioned forming an international secret fraternity and mutual-aid society called “The Society of the Free and Easy,” whose members would follow “the Thirteen Weeks Examination and Practice of the Virtues.” They were to profess that God governs the world and ought to be worshiped and “that the most acceptable Service of God is doing Good to Man.” This non-sectarian brotherhood, “begun & spread at first among young and single Men only,” was meant to develop into a global “united Party for Virtue.”

Due to his many other private and public concerns, the American founding father passed away in 1790 without having written a book expounding on his Art of Virtue and without laying the groundwork for a new international society. Nonetheless, since he described it in some detail in his popular autobiography, people interested in character improvement still had access to Franklin’s technique.

Nearly 20 years after Franklin’s death, the early Eastern European maskil (proponent of the Jewish Enlightenment movement) Rabbi Menahem Mendel Lefin of Satanów (1749-1826) completed and published a Hebrew text elaborating on Franklin’s character improvement method. However, Sefer Heshbon Ha-nefesh (Book of Spiritual Accounting) was not designed to “be serviceable to People in all Religions.” First published anonymously in 1808, it was written for the spiritual and moral edification of Lefin’s fellow Jews — namely, to help them subordinate the Animal Soul to the Divine Soul. The rabbi adapted Franklin’s method for use by what we would now call Orthodox Jews.

Lefin stated outright that he did not invent the method taught in his book. Yet he neglected to name Franklin or cite Franklin’s autobiography in Heshbon Ha-nefesh. Instead, he wrote elusively that “a few years ago, a new technique was discovered, and it is a wonderful innovation in this work [of subordinating the Animal Soul], and it seems, God willing, that its impact will spread quickly, as with the invention of the printing press that brought light to the world.” This omitting of Franklin’s name and of Franklin’s autobiography has led to much confusion in Jewish scholarship about Lefin’s source.

While basing himself on Franklin’s new technique for character improvement, including the use of grid charts, Lefin diverged from it in several ways.

Because Franklin had envisioned his method as universally applicable and as forming the basis for a global “United Party for Virtue,” he wanted a fixed set of 13 virtues that could be focused on by all prospective members. Lefin did not share this concern. Following Franklin, he detailed an initial list of 13 behavioral traits, but Lefin stressed that these were examples of what readers might choose to concentrate on. Later, in Heshbon Ha-nefesh, he offered five additional suggestions, including modesty, trust, and generosity. (Taking these 18 traits together, one finds that Lefin reproduced all of the autobiography’s 13 virtues — though, for example, mention of Socrates and Jesus, whom Franklin presents as models of the virtue of humility, is absent from Heshbon Ha-nefesh.)

Still, though he discarded Franklin’s ideas of a global “United Party for Virtue,” Lefin did not consider character improvement to be solely a private endeavor. He counseled fathers to monitor their sons’ characters for five years — beginning at age 13 (when a boy becomes a bar mitzvah) and continuing to age 18 (the age of greater independence) — after which time the sons, aided by their fathers’ observations of their adolescences and of the areas in which they were most in need of improvement, could embark on their own self-examinations. Lefin also advised that husbands and wives embark on character refinement together; that two friends form character study partnerships; and that men seek out different teachers who exemplified particular character traits they yearned for and whom they could emulate.

Professor Nancy Sinkoff noted in her excellent article “Benjamin Franklin in Jewish Eastern Europe: Cultural Appropriation in the Age of the Enlightenment” (2000) that Lefin had been drawn to Franklin’s method for the same reason that Franklin had been compelled to devise it. Both had “come to the conclusion that a practical program of behavior modification was necessary to effect individual change” and “that self-improvement required a structured plan of behavior modification.”

Because of Franklin’s approach to virtue and religion, Lefin was easily able to adapt the method and make its use part of accepted Jewish practice. From the outset, Franklin had wanted his system for character improvement to be universally accessible, and there were no obstacles preventing its subsequent incorporation into Judaism. Heshbon Ha-nefesh received the approbation of prominent rabbis, was embraced by the Musar movement — which concentrated on moral discipline and ethical refinement — and became one of the many Hebrew texts still studied in yeshivot, furthering Franklin’s initial goal of having his invention “be serviceable to People in all Religions.” (See here for a related The Wisdom Daily article about the Jewish use of Franklin’s method.) Over 230 years after his death, Franklin’s legacy of character development endures in Jewish thought and practice.

Shai Afsai (shaiafsai.com) lives in Providence. His writing has focused on Thomas Paine, Jews and Freemasonry, Zionist historiography, religious traditions of the Beta Yisrael Jewish community from Ethiopia, emerging Judaism in Nigeria, aliyah from R.I., Jewish pilgrimage to Ukraine, Benjamin Franklin’s influence on Judaism, Jewish-Polish relations, Jews and Irish literature, and Judaism in Northern Ireland.