I had the privilege of attending the opening performance of The Death of Klinghoffer on Monday night at the Metropolitan Opera. I say privilege because after months of listening to protests and nasty threats by fellow members of my tribe (Jewish), almost all of whom admittedly never saw the opera, seeing The Death of Klinghoffer was an extraordinary cultural and musical experience. The atmosphere, given the vocal demonstrations outside and the intense police presence inside, was crackling with energy. With so much public culture these days that’s either banal and trivial or shocking merely for shock value, this was theater at its best.

There was nervous anticipation, a perceptible readiness to be challenged artistically, musically, psychologically, and politically, serious conversation on security lines and even in the rest rooms, and yes the unease that comes with not knowing whether people deeply upset about the opera’s “perceived” anti-Semitism would disrupt the performance. (There were a couple of minor disturbances – one guy started repeatedly chanting, “The murder of Klinghoffer will never be forgiven!” – all handled with great professionalism by the Met. The disruptions actually became in some eerie tension provoking way part of the performance.)

This production of The Death of Klinghoffer is a tour de force, powerful and moving, and not anti-Semitic in the least. By now you may know, The Death of Klinghoffer is a 1991 opera by the acclaimed American composer John Adams with a libretto by Alice Goodman. It is loosely based on the 1985 hijacking of the Italian cruise ship Achille Lauro by Palestinian terrorists. During the hijacking, the Palestinians murdered Leon Klinghoffer, a wheelchair bound 69 year-old Jewish American.

Terrorists, however reprehensible their actions, are in fact human beings which is precisely what is so devastating about them and why crawling into what makes them tick all the more necessary.

But this opera is not a history lesson: it is a complex work of art designed to provoke mind, heart, and soul – to destabilize and rattle our fixed and reified views, beliefs, and story lines. The Death of Klinghoffer is a haunting, anguished, raw and mystical meditation on loss, exile, brutality and human suffering.

The opera begins with a pair of mournful, plaintive choruses – a Chorus of Exiled Palestinians followed by a Chorus of Exiled Jews. For the protesters this is the opera’s original sin – presenting two narratives flowing together as if they are equally true – moral equivalence accentuated by a backdrop of projected video images suggesting – one people’s security wall is the other’s apartheid wall. But there is no moral claim here. This is a psycho-cultural poetic claim that forces us, as painful as it may be, to hear what each side tries to deny: the dominant narratives of the Israelis and Palestinians are intertwined, paralyzing both peoples and hurling them towards a destiny of fury and death.

But this stirring and provocative work does not glorify terrorism. Yes, the terrorists offer rapturous and painful justifications for their violence: Mamoud, the most articulate terrorist sings how his mother and brother were killed in Palestinian refugee camps. But, Klinghoffer in his first aria courageously, angrily, defiantly, and poignantly stands up to the gun-wielding terrorists. He sings,

“I’ve never been a violent man… but somebody’s got to tell you the truth/ You don’t give a shit, / Excuse me, about your grandfather’s hut, / His sheep and his goat, / And the land he wore out. / You don’t give a shit, / You just want to see people die.”

The brutality of the terrorists is clear: when terrorists sing and violence threatens, the music is dissonant, pounding, terrifying and frenzied. In the original libretto, Klinghoffer is murdered off stage while here, Klinghoffer is brutally shot on stage – there is no explaining away the viciousness. And in the most devastating depiction of the hopeless abyss of vengeance in which Palestinians are mired, the first act ends with a ritual of a mother gifting a gun to her son.

I couldn’t help but think why aren’t Palestinians protesting outside. If I were a Palestinian I would be horrified by this depiction of all Palestinians as terrorists who believe their very identities are dependent on holding on to grievances (however justified) that have metastasized into the command to murder Jews.

The high ground in this work belongs to the Klinghoffers. Leon Klinghoffer’s aria of The Fallen Body, sung from his watery grave, is heroic. And Marilyn Klinghoffer’s final aria “You Embraced Them” in which she berates the Captain, laments her suffering, reveals her endurance, mourns her loss, and expresses her love is emotionally shattering in its beauty.? With her last words, “They should have killed me/I wanted to die” empathy and tears flow.

And yet hovering over the entire opera is the question too frightening to ask: What drives these Palestinians to murder the most vulnerable passenger? What causes human beings to become so distorted and twisted? It is easy to silence this question by labeling people evil, sub-human, and beasts. And while this may be a sufficient answer for rage-inducing pundits, fear-mongering leaders, craven politicians, and manipulated protesters it will not ultimately help us break the endless cycle of ever-deepening and horrifying death and destruction.

Terrorists, however reprehensible their actions, are in fact human beings which is precisely what is so devastating about them and why crawling into what makes them tick all the more necessary. We enter a death spiral when we confuse listening to a grievance, imagining a back story, trying to fathom the “cause” of terrorism with justifying and glorifying terrorists.? Terrorists may indeed need to be killed but without understanding the causes we will never end the murderous dance of terrorism. Perhaps this is why the most haunting moment in this opera is when the terrorists walk off the ship/stage right into the audience and up the aisle – exposed for their brutality yet alive to continue terrorizing.

Art is supposed to inspire exploration, understanding and even argument. The Death of Klinghoffer does this. It opens up space – as all meditations do – for terrifying truth. Both sides in this conflict believe they’re completely innocent and that the other side is completely guilty but whatever side we are on we’re not innocent. The tragedy is that no one really cares about this except the sufferers and they will not be able to speak to each other until they are ready to hear the partial truth (however partial it may be) of the other side. Until then, the earth, contracted by our inability to communicate, will continue to be soaked with the blood of innocents.

Coda:

Wearing my kippa/head covering, which identified me as a “traditional” Jew, I could feel the concerned looks of patrons when I walked into the Met as if my religious garb automatically made me suspect. Sadly, this is where American Jewry is these days. The more “traditional” and more deeply affiliated with “the community” the more one is assumed to be angry and judgmental, to rush to accuse others of being anti-Semitic (or self-hating), to demonize those with whom one disagrees, to suspect academics, artists, and the intellectual and cultural “elite”, and to see the world in general as increasingly hostile to Jews – and almost all of this anxiousness and anger surrounds the state of Israel and its conflict with the Palestinians. The Death of Klinghoffer was a perfect storm.

As I walked through a security gate onto the Lincoln Center mall protesters with veins bulging were screaming “shame on you, shame on you”. But the real shame was that a people known for its intellectual wrestling, its embrace of debate, and its understanding of the necessity for argument to uncover the ever expanding horizon of truth about human beings and life was so certain of their opinion about this work of art without even seeing it. The anger outside made the meditation inside all the more powerful and as I listened to the final stirring notes of this opera I shivered at the anger it created and how it left no way out and no consolation. For that we on the stage of history will need to find a way to speak to each other – something we on the streets of NYC on Monday evening didn’t seem much more capable of than those on the Met stage despite the final-curtain roaring standing ovations for The Death of Klinghoffer.

For further related reading on The Death of Klinghoffer, see “Solving the Prisoner’s Dilemma,” by Irwin Kula and Craig Hatkoff on forbes.com.

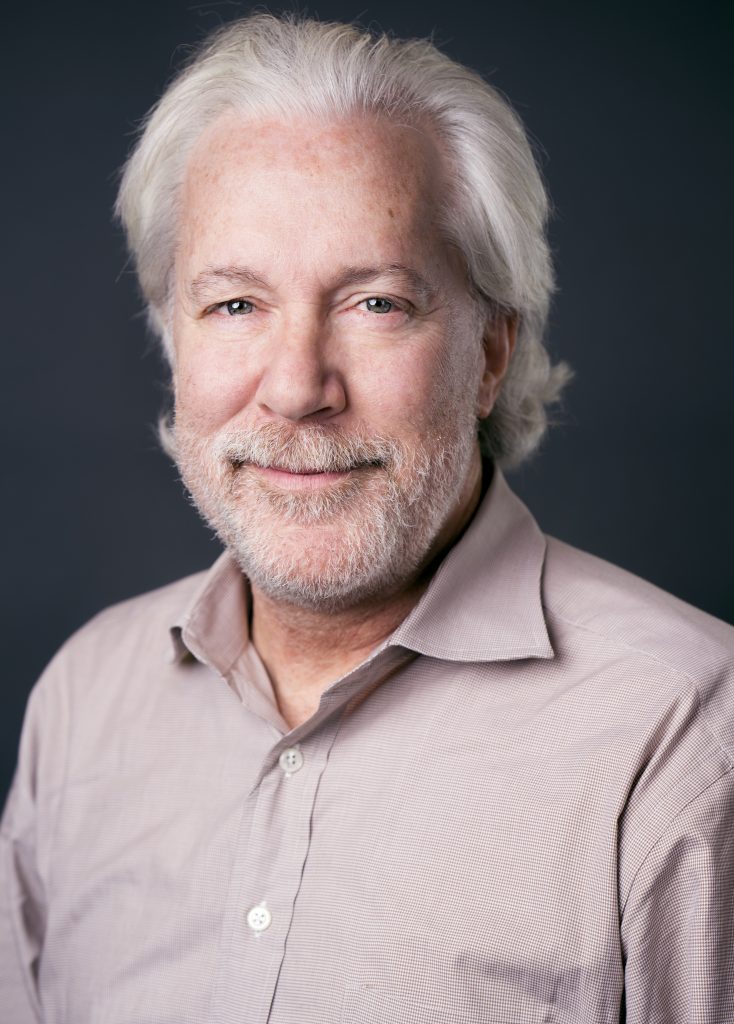

Rabbi Irwin Kula is a 7th generation rabbi and a disruptive spiritual innovator. A rogue thinker, author of the award-winning book, Yearnings: Embracing the Sacred Messiness of Life, and President-Emeritus of Clal – The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, he works at the intersection of religion, innovation, and human flourishing. A popular commentator in both new and traditional media, he is co-founder with Craig Hatkoff and the late Professor Clay Christensen of The Disruptor Foundation whose mission is to advance disruptive innovation theory and its application in societal critical domains. He serves as a consultant to a wide range of foundations, organizations, think tanks, and businesses and is on the leadership team of Coburn Ventures, where he offers uncommon inputs on cultural and societal change to institutional investors across sectors and companies worldwide.