There was a powerful confluence for me while studying last week’s assigned Torah portion alongside news coverage about the April 19 death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray. In Baltimore, Gray locked eyes with police and ran; when he was apprehended, officers radioed for a vehicle for transport. By the time the police van pulled into the precinct station, Gray had three broken vertebrae and a fractured voice box. He died of spinal injuries a few days later.

Demonstrations drew thousands of peaceful protesters. But in the aftermath of Gray’s funeral, Baltimore burned (a coalition of local leaders, clergy, and even alleged gang members have worked together to end the violence and repair the wreckage). Now the state’s attorney in Baltimore, Marilyn Mosby – whose parents were police officers – has announced that six officers will be charged in the homicide of Freddie Gray.

Loving others as we love ourselves [means] wanting for them all the things we want for ourselves.

Personally, I empathize with the viewpoint that riots can be an expression of hopelessness and grief, and that we should be angrier at those responsible for Freddie’s death than at those who have smashed windows in despair. I find myself thinking of Eric Garner, who died in police custody in Staten Island, N.Y., after being placed in a chokehold, gasping, “I can’t breathe.” I also think of Michael Brown, fatally shot by police while walking down the street in Ferguson, Mo. And I find myself thinking about what it must be like to live in this country without the privileges which my skin rewards me.

It’s facile, and often problematic, to claim that Torah justifies any given political position. People use scripture to justify every political stance. But I do think that last week’s Torah portion can speak to us today.

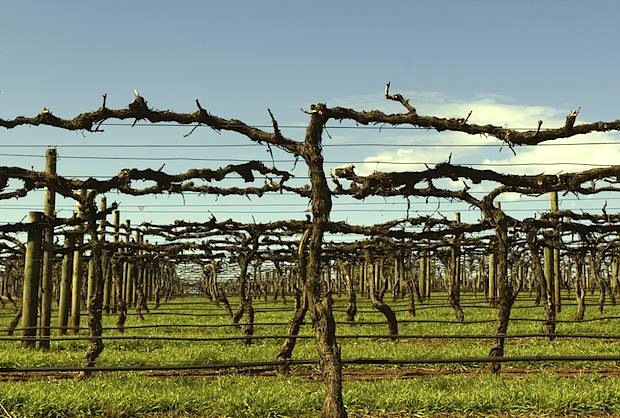

“You shall not pick your vineyard bare, nor gather the fallen fruit of your vineyard; you shall leave them for the poor and the stranger.” Fifty percent of those in Freddie Grey’s neighborhood are unemployed. There are whole communities living at or below the poverty line, and a disproportionate number of those living below the poverty line are non-white. Do our social systems provide for them the way the Torah’s system of gleaning aimed to do?

“You shall not render an unfair decision: do not favor the poor or show deference to the rich.” Do residents of Freddie Grey’s neighborhood trust the police and the justice system to live out that instruction?

“Do not stand idly by the blood of your fellow.” What can this instruction mean to those who fear that no matter what they do, they and their fellows will still be systemically mistreated and undervalued because of the circumstance of their birth or the color of their skin?

“You shall love your neighbor, your Other, as yourself.” This verse is at the heart of the Torah, both metaphorically and literally. This week’s Torah portion instructs us to be holy as God is holy. If this passage is a set of instructions for that process, then holiness means loving others as we love ourselves; wanting for them all the things we want for ourselves; ensuring that they live within a social system and a justice system which are as dedicated and lofty as we would want for ourselves. In the original context of Leviticus, the word ??? (“neighbor” or “other”) meant Israelite neighbor, your fellow who is like you and is part of your tribe. But I think this moment calls us to live in a spirit of post-triumphalism.

Ours is not the only path to God, and in this interconnected world, we are all neighbors. Every citizen of this country is my neighbor, deserving of equal rights and equal opportunities. Every citizen of this world is my neighbor, because each of us is enlivened by the same spark of divinity, and because the myth of our separateness has long been dispelled: what happens on this part of the planet impacts that part of the planet, and vice versa.

May the Torah’s voice call us to an honest accounting of our obligations to one another, and may we work toward the day when all human beings are truly afforded respect, dignity, and justice.

Since 2003, Rachel Barenblat has blogged as The Velveteen Rabbi. Ordained as a rabbi and spiritual director, she serves Congregation Beth Israel and is a founding builder at Bayit: Your Jewish Home. Her books of poetry include 70 faces: Torah poems (Phoenicia, 2011) and Texts to the Holy (Ben Yehuda, 2018).