The existence of Santa is arguably the sweetest, most pervasive deception the world has ever known. Created to enthrall children – and mercilessly used to sell heaps of stuff – Santa is one of the most recognizable and best loved cultural icons today. For the most part wholly secular, but with links to a Catholic saint, and brimming with characteristics borrowed from pre-Christian European mythologies, the once-multiple iterations of a fabled winter-gift-giver have coalesced into what is now a universally recognized personage with particular characteristics, and a rich, earth-bound existence.

It’s all a load of rubbish, of course, but it is compelling rubbish. A portly, rosy-cheeked, white-whiskered old man in a bright red suit with fluffy white trim, flying across the sky in a sleigh hitched to reindeer, for the sole purpose of giving gifts to children in the dead of night, leaving traces of his presence, but never being seen – except in stores in the weeks leading up to Christmas (a religious holiday about another fellow entirely – actually God if you’re a Christian), and is the source of unbridled joy if you are three or four (and still pretty intoxicating if you’re seven and know he doesn’t exist), and is pure pleasure for parents to fabricate, and is utterly delectable, in terms of profits, for many a merchant.

The name Santa is a shortening of Santa Claus, the English form of Sinterklaas, which is the Dutch derivation of Saint Nicholas. Saint Nicholas was born in the late 3rd century CE, to a rich family in the then-Greek town of Patara, in what is now Turkey. Orphaned as a small boy, he inherited a vast fortune, which he later gave away, thus earning a reputation for generosity and helping people in need.

He became Bishop of Myra as a young man, and was famed for his kindness, especially to children. Posthumously, he was canonized and made a Saint, and was given the Saint Day of December 6th (the day he died). Saint Nicholas’ popularity continued after his death, bringing with it a number of traditions that became attached to December 5th, the eve of his Saint Day, including the giving of gifts to well behaved children.

Some scholars contend that the Dutch Sinterklaas is a combination of Saint Nicholas and a much older, night-flying, gift-giver, thought to be derived from the Norse God, Odin, who flew through the sky on an eight-legged horse, and presided over the festival of Yule – a 12-day mid-winter hoolie, replete with feasting, drunkenness, mistletoe and decorated, indoor trees.

Whatever the truth, Sinterklaas is a big deal in Holland, and has festivities and parades held in his honor. Reminiscent of the later American Santa, he too is a white whiskered old man in a bright red suit (standard Bishop’s garb); he rides a white horse, and carries with him a big red book, in which is written whether children have been naughty or nice. He has a helper called, Zwarte Piet (Black Peter), who is an impish type character with a blackened face, thought to derive from when the Moors (North African Muslims who lived in the Iberian Peninsula) raided parts of Europe in the 16th century (though such a character exists in much older folklore). Once used as an incentive for children to behave (lest Swarte Pete carry them off to Spain), he is now the subject of intense debate and protest, due to what some believe (understandably so) is overt racism.

The Netherlands is not the only place to give Saint Nicholas (who is popular all over Europe) a punishing companion. Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic and Hungary (to name a few) have a fellow called Krampus, who is half-goat, half-man, and is often depicted carrying a whipping birch and a sack-full of children.

As for England, it abandoned Saint Day celebrations when it broke with the Roman Catholic Church in the 16th century (because Henry VIII wanted rid of his wife, so he could marry his lover, whose head he chopped off… and so on), and developed instead a paternal personification of Christmas known as, Father Christmas.

Although now synonymous with Santa Claus, Father Christmas is said to have nothing to do with Saint Nicholas (though he looks suspiciously similar) and was not aimed at children, but at feasting and merriment.

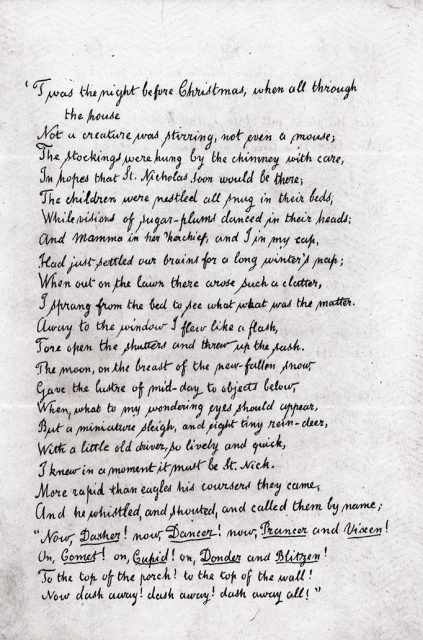

In the 19th century, elements of Sinterklaas, Father Christmas and (to confuse matters even more), the German, golden-haired baby (also a Christmas-gift-giver) called Christkind (who became known as Kris Kringle in America) merged into the now recognizable Santa, courtesy of a poem that appeared in a New York newspaper on December 23, 1823, entitled “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (latterly and better known as “The Night Before Christmas”).

Published anonymously, the poem was eventually claimed as the work of Episcopal Minister, Clement Clarke Moore (though this is contested), who was said to have written it for his children. The poem’s easy charm and enduring popularity have ensured that many of Moore’s fabrications of the jolly old elf– whom he refers to as St Nicholas – have become the mainstay of the Santa myth: most notably, 8 reindeer pulling a sleigh, a sack full of toys, stockings hung with care, naughty and nice lists, and his appearance on Christmas Eve, instead of St. Nicholas Day Eve.

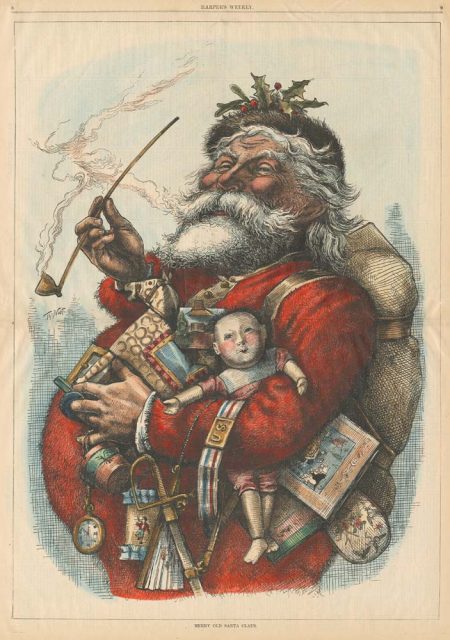

Decades later, political cartoonist, Thomas Nast – illustrating for Harper’s Weekly – set in ink what Moore had rendered in lyric; thus, giving the world the standard visual of Santa. Of course, neither Moore’s description nor Nast’s visual representation sprung fully-formed out of nowhere; rather, both drew on the longstanding European traditions as outlined above.

Moore’s and Nast’s Santa soon became an American phenomenon; which – coming as it did at the dawn of our rampant materialism – revolutionized Christmas, forming it into the gaudy, commercial ziggurat it is today. Santa now lives at the North Pole with his Mrs., has a slew of elves to make toys in his workshop – which is run like an industrial complex – is tracked by NASA on Christmas Eve, is the subject of countless songs, books, movies and ad campaigns, has long-since shed his European iterations, and has nothing whatsoever to do with Jesus (who, to be fair, co-opted December 25th from the Roman sun God, Mithra).

Eventually, the American Santa was fed back to Europe – especially Britain (which is no longer in Europe) and other English-speaking countries, namely, Australia and New Zealand, who have, in turn, given him their own flavor.

So, what does the future hold for Santa? Well, I guess while we continue our insatiable consumption of things we don’t need to survive, he will stay pretty much as he is; though I wouldn’t be surprised if he starts to get thinner.

Disclaimer:

Because Santa is a myth, he has fallen easy prey to successive layers of fabrication. Some of these layers of myth are relatively new, and some are very old; some have one source of origin, and others, multi-sources. The older and more multi-sourced a given layer (or characteristic), the more complex and convoluted it is, making it difficult to get at the truth (if there even be any). This being so, I found this article difficult to write; especially, as I am aware that people tend to be very passionate about their holiday traditions, whatever they be. Therefore, I humbly apologize if I’ve written anything that is contrary to your particular understanding of the Santa tradition.

Sources:

(2010) The Real Story of Christmas, The History Channel

St. Nicholas Center – Discovering the truth about Santa Claus

Rebecca is a painter, collage artist and writer. Originally from New Zealand, she now lives on a little Island in the Irish Sea. She has a degree in Religious Studies and is passionate about religious history, philosophy and esoteric goings on. Her favourite research topic is peculiar religious figures; those people who, through their devotion and vision of the divine, challenged the religious establishments to which they belonged, sometimes being crushed by those establishments, other times irrevocably changing them.

You can contact her and/or find her artwork and other writing on her website rebeccaodessa.com