Hope is a much-needed, often used, and often little understood concept. Haviva Ner-David is not only an accomplished rabbi, she is a rebbe of hope. Real hope, not naiveté, and not simply self-soothing, but bold, sometimes uncomfortable, and genuinely compassion-filled hope. Her newest book, Hope Valley, shares and inspires that kind of hope in the frame of a beautiful novel about two women — one a Palestinian world traveler, and one an American-born immigrant to Israel.

We recently sat down to talk together about hope in what is one of the most beautiful, hope-filled, and sometimes hope-crushing places I know — the modern land of Israel. Some call it Israel, some Palestine, some the Holy Land, and some a mash-up of all three, and this is not about debating which is correct, even as I have very strong opinions about that. This is about a book which invites and dares us to make space for both the strong opinions in our heads and the softer feelings that may be found in our hearts. Seems like a seriously valuable thing to me, especially these days, so enjoy the conversation, and take your own tour of Hope Valley when you read the book.

Let’s start with the title of your book, Hope Valley, in light of the fact that hope is generally thought of as uplifting and aspirational, while a valley is a low point, often carved out by the fracture of two previously connected geological formations. How do hope and valleys fit together?

Hope Valley is the name of the valley where Ruby and Tikvah meet. It’s the valley that divides Tikvah’s Moshav from Ruby’s village, a place of divide and brokenness. But when the two women meet in the middle, in a place between, there is hope, and Tikkun, fixing or healing, can take place. It’s like the golden cross which hovers throughout the novel – both in the 2000 front story and the 1948 backstory – on the horizon, above space and time, and is a symbol of hope. Tikkun is a thread throughout the book. The present and future can be a corrective on the past so that history won’t repeat itself. But this has to happen through deep healing, not just a band-aid. Ruby carries an open wound with her that needs healing, as do Tikvah and her husband, Alon, and really every character in the novel. I won’t give away the end, but suffice it to say that this is a hopeful book.

Very early on, in the first chapter of the book, you introduce an Israeli Palestinian who sneaks onto property thought of, at least by its Israeli Jewish owners, as belonging to them, with the explanation that “She had every right to be (there).” I was struck by the fact that that was, once upon a time how, I thought about my own presence in Hebron, not to mention how many disputants in the ongoing struggle for Jerusalem’s Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood speak. What do you make of that? Is the assertion of rights the right way to go? When yes, and when no?

The characters in the book are all flawed humans. Ruby, too. Ruby feels the land is hers, and Tikvah feels the land is hers. And they are both right – if you do believe in human ownership of land at all — but they are also both wrong if they feel it belongs only to them. That is what they both come to understand as they listen to each other, learn and grow.

There is a point at which Tikvah is in the library and finds a book with the history of hundreds of Arab villages that were destroyed in 1948. She discovers that, indeed, there was a large Arab village on the land where her moshav now stands, but she feels vindicated when she sees that it was a large, Jewish city originally.

Then there is another point of view in the book that says that there is no sense in trying to trace back who was there first, what matters now is the present. Tikvah’s husband, Alon, takes that to mean that what is important is only the more recent history, and he says to Ruby, “Maybe your father lived here before, and maybe my great-great-grandfather lived here even before that. The war is over. You attacked us, remember. And we won.”

But Tikvah takes this to a different place. She does feel that the past matters, but not to decide who has more claim, but rather because we cannot move past trauma until we acknowledge it and own it, and not whitewash it. Only then can we move past it and move forward together. And that, in the end, is what is most important – moving forward together. She says to herself: “Rehashing the past would lead nowhere. Was it possible to compare one people’s trauma to another’s? Who was to decide who had suffered more?” She comes to realize that rights are important, but they are also subjective, as is suffering. And sometimes one person’s rights can contradict another’s. That is where the nuances come in. It is not black and white, although many people today try to make it seem as if it is as if one group has all of the rights and the other does not.

As Tikvah, herself learns, nothing is guaranteed, and no one said life is fair. Pain and suffering are part of life. Ruby and Tikvah meet at a place that is beyond rights. It’s a place of human connection, a place of the heart, not the mind. That is why, in the end, rights are not what brings healing. It is love that brings healing. And it is from that place, I think, that we can move forward together – from a place that is beyond blame and right and wrong. In fact, that is one reason Tikvah names her dog Cane. One is because the dog is a part Canaan breed. But the other reason is because of Cain and Abel. Was he to blame for killing his brother? Or was it more complicated than that?

As the mystic Sufi poet Rumi says: “Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and right-doing, there is a field. I will meet you there.”

You draw repeated parallels between Ruby’s experience as a Palestinian refugee and that of Tikvah’s parents’ experience as Holocaust refugees. What would you say to those who might be deeply troubled by your drawing that parallel? What would you say to those who use it at every turn?

I was not implying that you can or should compare one people’s or one person’s suffering to another. There is no reason to compare or try to rate the level of their suffering. I really fail to understand why it upsets someone to acknowledge another people’s suffering. That does not negate yours. There is enough suffering in this world to go around. No one’s story is the same, and to say that your pain is not as big as mine is pointless. It is still pain.

I just watched a short documentary about the Israeli Jewish poet Avot Yehushurun. He lost his entire family in the Shoah. He was the only survivor. Yet, when he fought in 1948 in Palestine and witnessed the clearing out of Arab villages, he was aghast. He said he could never condone making another people refugees after what the Jews had been through. He said he could not condone that. As Ruby says, “Being the victims of victims does not make my people feel any better.”

But I also very much understand that the personal and collective trauma of the Shoah is very alive, still, even for me. I felt it viscerally during this past war with Gaza and the rioting that erupted here in Israel. The part of me that is afraid of being rounded up and killed just because I am a Jew is still there inside of me, even after all of the inner work that I’ve done. That part of me needs to be reassured when she’s triggered and put on the defensive. At the same time that we need to make sure that kind of suffering does not happen to others because we know what it feels like to have suffered, we also need to make sure it does not happen to us again. Jews also have a right to live, which is not the message a lot of Jews these days are feeling, which then puts them on the defensive. Not only Palestinians are afraid and feel threatened. It goes both ways, and all of that fear is legitimate and needs to be acknowledged and allayed. But it can only be allayed through building trust and perhaps, eventually, even reaching a place of deep caring, even love.

The act of foraging plays an ongoing role in the story, and it’s a powerful metaphor. Where do you forage, and for what are you looking?

Do you mean this literally or metaphorically?

Literally, I forage in the forest behind and around Hannaton, where I live. I forage there for wild mushrooms. And in the surrounding wild fields, there is lots of Hubeiza (mallow), and all sorts of other wild plants, to forage. My 10-year-old daughter, Shefa, is the most knowledgeable about what is and is not edible around here, actually.

But if you mean metaphorically, foraging is not farming. It’s about collecting what nature provides, and it’s not premeditated or planned. It’s about being open to what the Universe provides, what life sends you, and relinquishing control. As Ruby calls it: surrendering to the flow. In fact, there is a scene in the book where the two women do a prostration pose together out at the edge of the forest, an embodied surrendering to the flow. Both women live with serious illness, and that is a theme throughout the book – relinquishing the control we never really had anyway.

But in life, as in foraging, you need to be able, as Ruby tells Tikvah, to discern between what is poisonous and what is healthy. And sometimes they can be deceptively alike. It is often hard to know what is the right way to go. I feel that very strongly now, here in Israel. And that is where intuition and experience play a role, Ruby says. She also says that while you have to be careful, you also can’t let fear paralyze you or prevent you from taking risks.

You present both a Jewish and a Palestinian narrative and do so with genuine respect and reverence for the authenticity of both. It seems that for one character — Ruby — it is about sharing her story, while for Tikvah, it is more about discovering her ignorance, on so many levels. Given your deep commitment to equal dignity, why did you make that choice?

This was not a conscious “choice” exactly. I am telling a story with characters who say and do things that are not necessarily what I would say or do. In the case of these two characters, this is the story I wanted to tell, and these are the characters I chose to help me tell it. I wanted to tell the story of a Jewish woman who moves to Israel because of her Zionist ideology — having been exposed to only the Jewish Zionist narrative — and who is exposed to the Palestinian narrative, in a very personal way. I wanted to explore how this would affect her and how she would react. (I admit this is somewhat autobiographical, although Tikvah is not me and her character and story are very different from mine.)

Ruby, on the other hand, is more knowledgeable about the Jewish narrative than Tikvah is about the Palestinian narrative. And that is often the case here in Israel because Jews are the majority and Palestinian Israelis the minority. The Zionist narrative is all around us here. Zionist history is taught in Arab schools, but it is forbidden to teach the Nakba in Israel. And Israel has definitely covered up a lot of what happened in 1948 or at least whitewashed it.

Of course, there are many Palestinians who do not know about the Shoah, for example or don’t believe it is true. But Ruby is a savvy woman of the world. She traveled the world for 25 years before coming back to Israel for cancer treatments, which is when we meet her. Her work is not to be “woke” to the facts but rather to forgive and move past her resentments and understand that Tikvah and Alon, too, suffered, and that they, too, have a claim to the land, and that they are not going anywhere, so she had better find a way to share the land rather than shoot herself in the foot by carrying her resentment around, weighing her down. She even says at some point that she knows the Jews have suffered and that the Palestinians were also responsible for what happened to them in 1948.

But because of the current power imbalance in Israel, it is more in the hands of Jews to right the wrong. Jewish Israelis do carry a lot of the responsibility. But as is also expressed in the book, we can say we are sorry without it meaning that we are the only ones to blame. We can be sorry for causing suffering even if our actions were totally understandable under the circumstances. But yes, I feel very strongly that both women have to acknowledge each other’s narratives. Otherwise, it won’t work. It’s just switching one people’s sovereignty for another’s. What I am seeing now in the rest of the world, is that it is actually the Palestinian narrative that is more well known, and that people are simply privileging that narrative rather than holding both narratives together as legitimate, seeing that both are true but both are also not the whole picture. Until we can see that whole picture, we are in trouble. As Ruby says to Tikvah: “Ironically, moving out of your own narrow view of things can give you more focus, at the same time that it makes you realize how ephemeral and relative it all is.”

This is a story of love and betrayal. How are the two intermingled for you, not only when it comes to thinking about the land, but when it comes to thinking about life?

That’s a big question. A theme throughout the book is how love and loss are inevitably intermingled. You cannot have love without loss, and in order to feel real loss, you do have to allow yourself to feel attached. And sometimes we betray most those whom we love the most, not out of a lack of caring, but out of caring perhaps too much if that is possible. Not really caring too much, but more not directing the caring properly, or not being able to make healthy decisions because of all of that caring. I don’t want to give away too much, but I can say that this is true for some central characters in the novel.

Land, and attachment to it, are huge issues in the story, and you seem to both deeply appreciate that, and to take a mostly dim view of such attachments. Tell us about both perspectives, and how you/we can honor both.

One benefit of fiction is that you can have different characters with different points of view. That is one reason why I chose that genre to tell this story – because of the complexity of the situation and the multiple points of view. Both female protagonists, for example, especially Ruby, are very attached to the land. But they are also very aware of the ways in which that attachment causes conflict. This is all played out with the microcosm of the house. I will not be giving too much away if I say that Tikvah is living in Ruby’s father’s family house. They discover this, too, early on, which is why Ruby tries to befriend Tikvah at first. She is looking for the diary that her father, Jamal, left in the house in 1948 when his village was emptied and most of it razed. At first, the two women fight over the house. It causes strife between them. What they need to do is learn how to share the house, and not only that but teach others to do so as well. I won’t tell you if they succeed or not, but that is what the reader is hoping they will do, I think.

Ruby’s father, Jamal, wrote sagely of life being composed of “honey and onions.” What is the honey and what are the onions for you — both when it comes to living in the land and the State of Israel?

The intensity of life here can sometimes be honey and sometimes be an onion. The same with the feeling of belonging and responsibility. It depends on the day. Really everything about it has its good side and bad side. It’s a tiny country, which creates a real sense of intimacy with the place and its people but can also feel stifling at times. The actual saying is “Yom asal, Yom basal.” (Day of honey, day of onion.” Meaning that there are good days and bad days, and you have to take the bad with the good. But there is also the even larger existential idea, as you point out, of everything in life having its “good” and “bad” side. But that is a very binary way of looking at the world. A more integrative approach would say that they are really all the same thing, or that you can’t have one without the other.

Writers are often changed by the writing. What, if anything, has shifted or changed for you, through the writing of Hope Valley?

Ironically, I developed more sympathy for Alon and Tikvah, I think. Perhaps because I am a woman and, like the two women, live with serious illness, my inclination is to see the side of the underdog (as Tikvah says about herself), or the oppressed. And so, living here in Israel as Jew in a Jewish country, I feel drawn to the plight of the minority who are not Jewish and who are therefore less privileged living in a Jewish state. But having to write from the points of view of both the Jewish and the Palestinian characters, I had to really feel the pain of both peoples, and this was important work for me. A kind of reminder to myself of the nuances involved in the conflict and that the Jews are not the only ones who bear responsibility, that there is a deep pain that Jews carry as well and that we cannot turn back history. Decisions were made, things happened, and all not without good reason. The question now is how to deal with the current reality.

Writing this book also helped me connect more to that place inside of myself that is afraid of anti-Semitism and that is not so ready to give up on this place or give it away. I won’t give away the end of the book, but I can say that I was not sure how it would end. I did not know what would happen with the house. I was somewhat surprised myself as to what Tikvah decides to do in the end. Writing her character and coming to this decision from that place, was transformative in some ways. As was writing from the Palestinian characters’ points of view, of course. I had to really feel into their suffering and resentment. This was all based on listening to the stories of real people, of course. But the final writing of these characters that I created came through me.

What did I not ask you, but you wish I had?

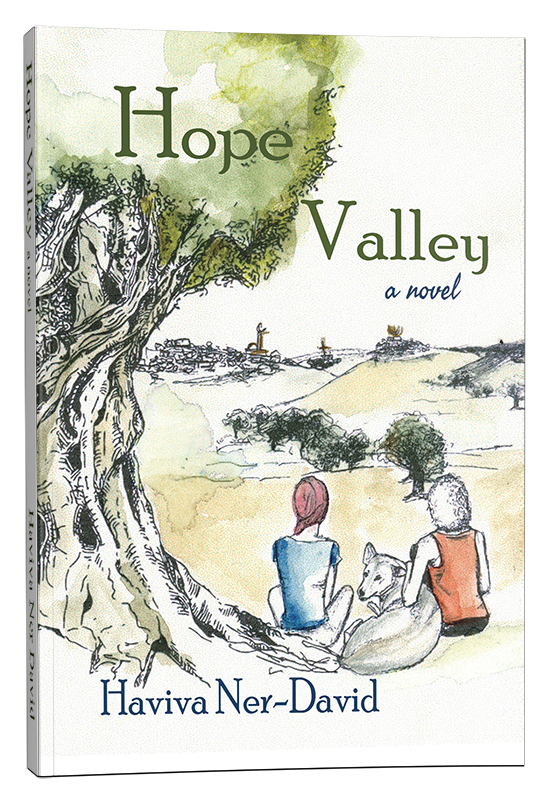

Well, I did think you would ask me something about the interfaith element of the book, which is apparent from the cover art, with the three Abrahamic religious symbols in the valley. There is also the ancient olive tree, which is there in both the front and backstories. Legend has it that it was planted by Jesus’ father, Joseph, who was a Jew. The tree has three trunks (symbolic of the three Abrahamic faiths) that form a canopy above those who sit beneath it (in the book, it is two interfaith couples who do so). It is a symbol of the place where we are all connected, like the golden cross that hovers on the horizon throughout the book (in both the back and front stories), which is beyond time and place and symbolizes hope. In other words, hope lies in the place where we can find common ground and connect as human beings.

There is so much more to say. I really hope people will read the novel and be in touch with me with any questions. I am very accessible and love to talk about the novel. I am also very happy to do Zoom book talks with groups before or after they read the novel.

What’s next for you?

I want to throw out there the idea of having Hope Valley translated into Arabic and Hebrew. Especially now, in our current divisive political climate, it is so important to hear both Ruby’s and Tikvah’s stories. I think this book can be an especially helpful tool for dialogue and mutual understanding. I also think it would be a good idea to get the book into high school and college curriculums, as from what I can see, the picture of what goes on here in Israel is simplistic, one-sided, and distorted.

As for other projects, I have a third memoir coming out at the end of the year: Dreaming Against the Current: A Rabbi’s Soul Journey, As well as a book helping couples prepare for marriage and their wedding. I am also working on a few children’s book ideas. And I have some ideas for the next novels, too. I am also not only a writer. I do a lot of other work, too. As a rabbi, I have a thriving spiritual companioning practice, and I also run the only mikveh in Israel open to all humans to immerse as and when they wish. I meet with groups there and do individualized immersion ceremonies. It’s a very special place.

Listed for many years in Newsweek as one of America’s “50 Most Influential Rabbis” and recognized as one of our nation’s leading “Preachers and Teachers,” by Beliefnet.com, Rabbi Brad Hirschfield serves as the President of Clal–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a training institute, think tank, and resource center nurturing religious and intellectual pluralism within the Jewish community, and the wider world, preparing people to meet the biggest challenges we face in our increasingly polarized world.

An ordained Orthodox rabbi who studied for his PhD and taught at The Jewish Theological Seminary, he has also taught the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs an ongoing seminar, and American Jewish University. Rabbi Brad regularly teaches and consults for the US Army and United States Department of Defense, religious organizations — Jewish and Christian — including United Seminary (Methodist), Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (Modern Orthodox) Luther Seminary (Lutheran), and The Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative) — civic organizations including No Labels, Odyssey Impact, and The Aspen Institute, numerous Jewish Federations, and a variety of communal and family foundations.

Hirschfield is the author and editor of numerous books, including You Don’t Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism, writes a column for Religion News Service, and appears regularly on TV and radio in outlets ranging from The Washington Post to Fox News Channel. He is also the founder of the Stand and See Fellowship, which brings hundreds of Christian religious leaders to Israel, preparing them to address the increasing polarization around Middle East issues — and really all currently polarizing issues at home and abroad — with six words, “It’s more complicated than we know.”