Over the last few months, there has been a sharp spike in a particular niche of Google results. It’s not searches for how to save your shoveled-out parking spot or how I can make my AI interface more kind. Rather, the spike is for what has come to be known as “competency porn.” Although apocryphally claimed to have originated in 2009, the term has found its footing in recent years. It’s best described as the pleasure derived from watching a highly skilled practitioner, either in the real world or fictional one, demonstrate expertise.

One can see this in the myriad social media videos with millions of views for simple tasks like making cakes, hanging pictures, or fixing toilets. In entertainment, think about medical procedurals like HBO’s The Pitt or Netflix’s political hit The Diplomat. As Washington Post columnist Jada Yuan notes, “There is something comforting about spending time with very smart, well-intentioned people.”

That’s the tension. Look at the events of the world around us. Globally, the war between Russia and Ukraine continues. The United States toppled a foreign government in Venezuela with no next steps in place. Domestically, the country is facing tectonic shifts as government agencies are being investigated for crimes against citizens. For the Jewish community in Israel and the Diaspora, we’re only now coming out of the fog of a multi-year war between Israel and Hamas. Being able to cocoon ourselves in competency is understandable. But there’s something deeper going on here, and I want to explore that connection through our parshah this week, Yitro.

Moses’ father-in-law, Yitro, sees Moses struggling with the weight of leading the Israelites. After telling Moses that he can’t bear the burdens alone, Yitro suggests delegating some power. In his wisdom, he passes along some character traits that may be useful. In their initial conversation in Exodus 18:21, we read the following recommendation from Yitro to Moses:

“You shall also seek out, from among all the people, capable individuals who fear God—trustworthy ones who spurn ill-gotten gain. Set these over them as chiefs of thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens.”

The translation makes it a bit clunky, but in essence, the four attributes he suggests are capable, God-fearing, truthful, and ethical. It’s a solid list from which to build a cadre of leaders. But then, when Moses puts the plan into action four verses later, we read:

“Moses chose capable individuals out of all Israel, and appointed them heads over the people—chiefs of thousands, hundreds, fifties, and tens.”

As you can see, only “capable individuals” makes the cut when Moses executes the plan. Some commentators argue that the other attributes are implied and that “capable” serves as an umbrella phrase. But a deeper meaning can be found when we actually unpack what “capable” means here.

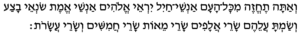

In the Hebrew, “capable” is being translated from the phrase ![]() . That moniker, anshei chayil, could be more literally translated as “strong individuals.” Chayil is a word often associated with militaristic might and physical power. Singling it out here, the text seems to want us to understand that these leaders Moses is seeking out shouldn’t just be ethically, spiritually, and truthfully minded; they should also be strong.

. That moniker, anshei chayil, could be more literally translated as “strong individuals.” Chayil is a word often associated with militaristic might and physical power. Singling it out here, the text seems to want us to understand that these leaders Moses is seeking out shouldn’t just be ethically, spiritually, and truthfully minded; they should also be strong.

But what is strength here?

One tantalizing take comes from the Mei Hashiloah, the great Chasidic master from Ishbitza in the 19th century:

Moses only focused on strength as one of the four attributes. This is because the phrase “strong people” hints at an awareness these types of people have in that their strength is not really their own. Rather, it is a strength that comes from the Divine. True strength is the ability to recognize that your strength is not really your own.

Speaking to an audience that is operating with a distinct theological bent, the Mei Hashiloah says that the strongest person is the one who has the strongest belief in God and recognizes that one’s capabilities are not intrinsically one’s own. Those capabilities come from other places.

I want to broaden what he is saying. Our strength as individuals does not come from having all the answers or skills. In fact, the more we can recognize that our strength probably comes from a multitude of forces external to ourselves, the more we can grow. That feels very resonant to this current desire for competency porn.

Recognizing we can rely on others is not always society’s definition of “strong.” After all, the rugged individualism of Western culture might argue the opposite: You should pull yourself up by tapping into your own inner resolve. This is true to a point, but it has its limits, and we can see that in the chaos of the world around us, when individuals try to project strength by acting as saviors, but instead only end up sowing chaos.

This helps explain why, on a psychological level, “competency porn” is so alluring. Mirror neurons, which fire when we observe the behavior of others, are activated when watching competency. In other words, seeing someone expertly do something gives us satisfaction not just at what they did but how they did it. The other reward we get is cognitive closure. Seeing something complex come to a safe end makes us, in turn, feel safe.

Both of these psychological processes involve us expanding beyond just ourselves. We limit ourselves by thinking all problems fall to us to solve. So much of what drives the success of characters on the television shows that have amassed devoted followings is their ability to work together. Just as Yitro taught Moses, and our own psyches are signaling to us, it’s okay to look for help or, in this case, competency from the world around us.

In a 2005 commencement speech to Kenyon College graduates, author David Foster Wallace shared the following anecdote:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?”

What we see around us doesn’t need to be our reality. We can take steps to change it. We still have agency, even in this tempest of a world. We can look to others to aid us, not for superhuman feats of strength or Mensa-level genius, but for their simple competency. In linking ourselves to them, we might realize that we’re more competent and capable than we actually realize.