After Moses and the Israelites cross the Reed Sea, they break into song praising God for saving them from their enemies. This ancient poem, which remains part of the daily morning liturgy, begins with these words (Exodus 15:1):

I will sing to the Lord, for He has triumphed gloriously; Horse and driver He has hurled into the sea.

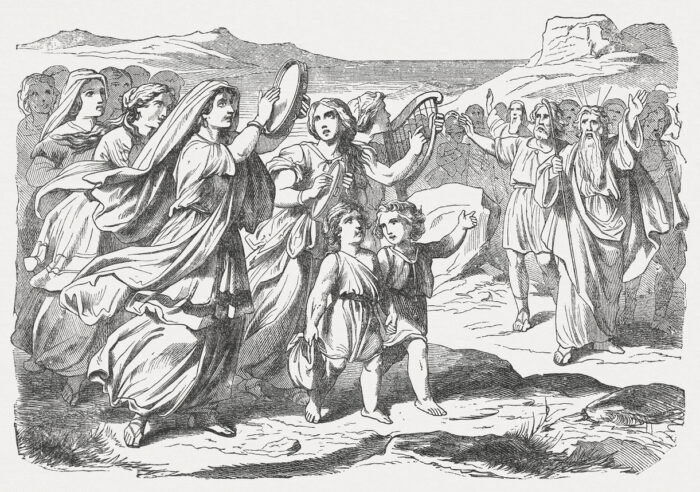

The text continues with the song for eighteen verses. Then, one verse later, we read of Miriam leading her own group in song and dance:

Then Miriam the prophetess, Aaron’s sister, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women went out after her in dance with timbrels. And Miriam chanted for them: Sing to the Lord, for He has triumphed gloriously; Horse and driver He has hurled into the sea.

Strangely, Miriam’s song ends abruptly, leaving us with a question of what exactly did she sing? Furthermore, were women singing at the same time as the men or separately? Generations of interpreters have offered a variety of explanations. During the period of the Second Temple, Philo of Alexandria (25BCE-50CE) writes that the women sang the same song together with the men:

This wonderful sight and experience, an act transcending word and thought and hope, so filled with ecstasy both men and women that, forming a single choir, they sang hymns of thanksgiving to God their Savior, the men led by the prophet Moses and the women by the prophetess Miriam.

A fascinating Dead Sea Scroll fragment (4Q365), from a cache of hundreds of ancient Jewish sacred texts discovered in the desert in the 1940-50s and previously unknown to us, describes a new and different song that was sung separately by the women:

The enemy’s hope has perished and he is forgotten…They have perished in the mighty waters…Praise him in the heights, he has given salvation…

This debate between ancient biblical exegetes about whether the women sang together or separately and whether they sang the same song or a different one continued for centuries among the rabbis as well. The great rabbi Sa’adia Gaon (882-942CE), following the Mekhilta, proposes that the women recited separately the same entire song responsively with Miram, even though the Torah only recorded the beginning. Another possibility is that Miriam and the women sang with the men only the one-line chorus in response to the full song of Moses. Or that Miriam repeated to the women each verse as she heard it from Moshe (as suggested by the commentator Abarbanel). Rabbi Haim Yosef David Azulai (aka the Hid”a, 1724-1806) writes concerning the Haftarah that accompanies this parashah, in which Deborah the Prophetess wins a war and also sings a song of victory, that Deborah sang her song to the men as well as the women, suggesting that Miriam may have done the same. The Netziv (1817-1893), on the other hand, argues that the women composed and sang separately their own long song, but that only the chorus of that song was recorded in the Torah. I wonder if the Netziv would have felt vindicated by the Dead Sea Scrolls fragment had he lived to see it!

Our modern communities continue to contend with how to bring together an array of voices and values, whether it is diversity of gender, country of origin, political persuasion, level of observance, or any other affiliations and preferences. The commentaries above lay out at least four models. First, one can keep the groups separate even as they recite the same words and conform to one structure (Saadia Gaon). Second, the groups can remain separate with each performing a variation of the ritual that conforms better with their respective views (Dead Sea Scroll and Netziv). Third, the congregation can come together as one, even if it means that one group agrees to follow the lead of the other (Abarbanel and Hid”a, though in opposite directions). Fourth, the groups can come together fully on equal footing when the common goal inspires them to put other differences aside (Philo). We continue to seek out the best way for all members of our congregations to find their roles and unique voices within the framework of our communal prayers and rituals. As we do so, let us look to Miriam’s song—in its array of interpretations—as a model.