When I was a kid, g?d was a big dude in the sky with a beard. A friendly guy, but still a guy. This guy kept track of the morality of the world, punishing the bad and rewarding the good. I thought this was Judaism’s idea of g?d — at least it seemed that way from the Torah stories and prayers I learned. Plus, my teachers never gave me another alternative, so this was it. As I grew up, and specifically after my own father passed away, I stopped being able to believe in this version of g?d. I was embarrassed by my own previous beliefs, feeling a little foolish. But as an educator, I know now that it is totally understandable for a child to see g?d as the “dude in the sky.” (This video has more of my thoughts on the subject.) It can be a comforting image, but one that raises a lot of questions, especially as they get older. If g?d is so powerful, why are people hungry or sick? Does anyone hear our prayers? These questions arise out of the discrepancy between the g?d ideas we learn and the world in which we live.

A big piece of the puzzle is language. Hear “King of the Universe” enough times, and it’s understandable how g?d might be a dude in the sky. But the g?d-language gifted to us by our spiritual ancestors is much more expansive than that. Below is a guided mindful learning experience to help crack the lid open on that expansiveness. You can journal the questions as you go, or discuss them with a chevruta (study-partner). Take a moment to breathe, perhaps to put a hand on your heart and set an intention for curiosity and openness, and let’s begin.

g!d’s Nicknames

What are some Hebrew names you’ve heard used for g?d before?

We can think of all of these like nicknames for g?d. Loving, intimate names, or names based on action, or names based on values. But what is g?d’s “proper name” in Hebrew?

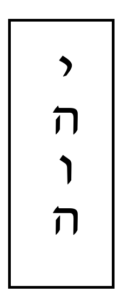

That name is spelled yud, hey, vav, and hey. If you saw this name written out and you have experience in Jewish prayer services, you might pronounce it Adonai, which means “my Lord” (technically, “my Lords”).

What are some associations you have with the word “Lord”? Maybe male, powerful, ancient..

But yud, hey, vav, and hey does not spell Adonai. We use Adonai here as a nickname.

Saying and Embodying

Why do you think we don’t say yud hey vav hey out loud?

We actually can’t. The vowels were lost long ago, and it’s impossible to say the name without vowels. Try to pronounce a yud or a vav, and feel the pressure in your throat. Say a hey without a vowel- it’s an outbreath. 1

We can also feel it in a different way. Take a look at these letters, vertically this time: We can map them onto our bodies and see how it feels.

We can map them onto our bodies and see how it feels.

Stand up if you can. Feel your feet on the ground, bend your knees. Feel supported by the earth. Now roll your shoulders back and stand tall, feeling where the top of your head meets the air around it.

Now, using your imagination, picture that your head is a beautiful yud, the top reaching up and the bottom reaching down.

- Imagine that your torso and arms are a hey. Does that change how you stand?

- Imagine your spine is a vav, straight and tall. Feel yourself straighten up.

- And imagine your legs are the last hey, rooting you in the earth.

- Imagine that your body is the name. Yud, hey, vav, hey…

How would the world be different if we treated every person like a walking, talking name of g?d?

g!d As All-That-Is

So, we can’t pronounce yud hey vav hey, but we can feel it, and we can embody it. That’s a lot like how we experience yud hey vav hey in the world. We have moments of connection, of holiness. We feel part of something greater than ourselves. We feel hope, we imagine what the world could be. And it’s difficult to put into words, but we can feel it, and we can try to be it. And we try to put it into words anyway.

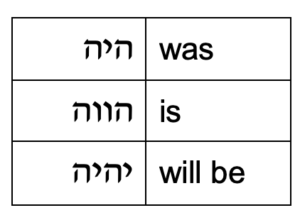

But just like any Hebrew word, yud hey vav hey has a root. The root is, “is!” You can see it in the Hebrew verb form ![]() , “to be.” And in the past, present, and future tense:

, “to be.” And in the past, present, and future tense:  See how the same letters are contained in this name. The closest translation of YHVH we have is “being” or “is-ness” or “all-that-is.” And that’s very different from “Lord.”

See how the same letters are contained in this name. The closest translation of YHVH we have is “being” or “is-ness” or “all-that-is.” And that’s very different from “Lord.”

How might it be different to relate to g?d as “all-that-is” vs “Lord?” Try “blessed are You, Lord” and then “blessed are You, all-that-is.” How does it feel? What do you notice?

Yud-hey-vav-hey is like g?d’s “proper” name in Hebrew. We can view all other g?d-names as nicknames. In Anim Zemirot, a liturgical poem in the closing prayers of the Shabbat morning service, the author reminds us that g?d is named according to deeds: what we see of the Divine in the world, filtered through our own imagination. When we come across a nickname for g?d in the siddur or Torah, we can remember that a person wrote this name. A person called out to g?d in this language, using this poetic imagery. We can approach each nickname with curiosity: Why this name? What aspect of the Holy One does it seek to elevate? Is it descriptive, attempting to distill the world as it is, or aspirational, hoping for the world we want to see?

g!d As King

We can also go a little deeper. Just as with any Torah story or ritual, g?d nicknames are full of midrashic, meaning-making potential. The more layers we uncover, the more points of connection we can find. As an example, let’s look at the nickname melech, translated as “king” or “ruler.” Melech is used in the blessing formula, so it’s pretty ubiquitous. When we read it literally, the name melech can conjure up that Dude-in-the-sky image of a king on a heavenly throne. What might happen if we go beyond this literal meaning?

When we think of an earthly king, what attributes come to mind? Definitely power, but what is that power used for? To govern and build cities, yes, but also to subjugate people, to extract resources, and to wage war. The Rabbis used the name melech for g?d often because a king was the most powerful person on earth. But that isn’t to say that g?d is like a regular earthly king, but that perhaps earthly kings should aspire to be more like g?d-as-king. So, how does g?d-as-king use their power?

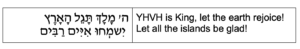

In Psalm 97, which we recite in our liturgy during Kabbalat Shabbat, we read:

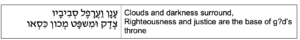

This is where we might instinctively say, “No g?d is not a king!” But the next line tells us more:

In the poetic imagination of the psalmist, g?d-as-King sits on a throne made not of gold and jewels, but made of the values of righteousness and justice. That is a statement of the kind of world we should be working towards, and the kind of leaders we need to have and be. In our sacred heritage, g?d-as-King uses g?d’s power not for war and subjugation, but for justice. g?d-as-King cares for the widow and the orphan. Do we? When we read this as poetry, we give it back its power to move us, to imagine what a better world could look like.

We can also dig deeper into the Hebrew itself. Mystical tradition explores melech as an acronym for:

Mem – Moach (mind)

Lamed – Lev (heart)

Kaf – Kaved (liver) OR K’layot (guts/intuition)

When we call g?d Melech, we acknowledge the unity and importance of all three levels, whether the last level is the body or the intuition. We can reflect on how we are guided, how we make decisions, and how to raise all parts of us to the level of holiness.

Your Names for g!d

Does reading these teachings change how you view the name Melech?

What are other interpretations you can come up with for that name?

And if it’s still not connecting, what is a name you might use instead?

May we be able to take this expansiveness out into the world with us — recognizing the divine name in each person we meet, the limits and beauty of the language we weave, and stay open to the mystery.

- Learned from Cantor Ellen Dreskin[↩]