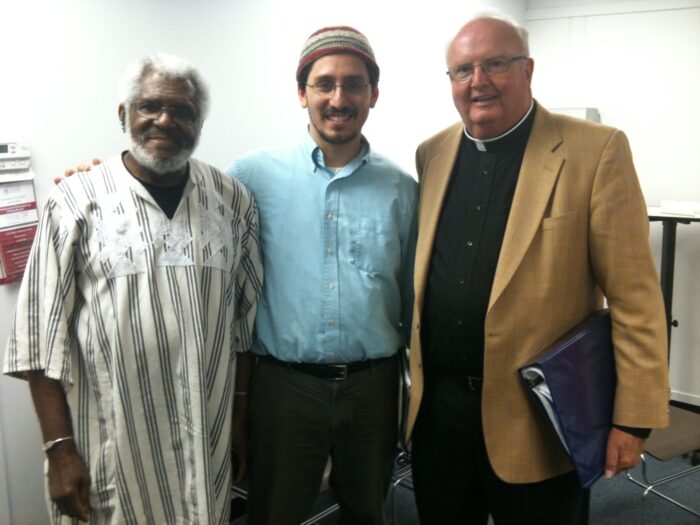

“A rabbi, a priest, and an Imam walk into a classroom.” For ten years, that line wasn’t simply the hook for a classic joke, it was a weekly ritual for me. Alongside Father Jack Baron and Dr. Sheikh Imam Ibrahim Abdul-Malik, I co-taught a university-level course called “One G-d, Three Paths” at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Teaneck, New Jersey. We were together in the classroom for two and a half hours, one night a week, discussing and debating, both with students and each other, the different tenets of our Abrahamic faith traditions. If you want to get to know what someone of a different faith tradition believes and thinks about G-d, human suffering, and what the future should look like, teach a class on theological history with them.

The course textbook, chosen by Father Jack, was called, The History of G-d: The 4,000 Year Quest of Judaism, Christianity and Islam by Dr. Karen Armstrong. We taught students about Mohammad’s vision, Jesus’s transformation, and Abraham’s covenant. We agreed about a lot of things. And we disagreed about many things. And we learned and modeled disagreeing with grace and respect—respect for opposing views that Father Jack would lament was often missing in our public discourse. Father Jack of course had no children of his own, and he would say this course was his baby. He conceived of it and for over 20 years made it a featured course in the Humanities department at Fairleigh Dickinson University. Even into retirement, Father Jack took steps to ensure this class would continue without him: He entrusted that task to me. I became the lead faculty member.

When Dr. Ibrahim passed away in the spring of 2020, we were devastated, but worked quickly to find another Imam to join us. I had promised Father Jack I would continue the vision of this class. And then in the winter of 2022, Father Jack unexpectedly passed away. I was asked to speak at his funeral, a rarity for a rabbi in a Catholic church. In my remarks, I spoke about the course and my commitment to keep it going.

Another Christian clergy member was hired for the role and the class continued, but it was not the same. While the academic content was similar, we couldn’t replicate the chemistry of the original three instructors. I tried to hold on to the spirit that guided the class for so long. A year after Father Jack’s passing, alongside Dr. Ibrahim’s granddaughter, I organized a Zoom memorial to honor the lives of these two men together. It was inspiring to have former students, friends, former faculty members, and family show up for this event—which also coincided with the date that would have been Dr. Ibrahim’s 100th birthday. He was a force of nature.

Without them, it was hard to form a cohesive teaching unit. We lost one priest faculty member to disability. Another Imam moved across the country after completing one semester. Another Imam did not have a car and needed to take three hours of public transportation in each direction just to make it to the university. We could not offer much in the way of compensation, since the three faculty were splitting the wage of one adjunct faculty class.

Three years have passed since father Jack’s death, and I just made the painfully difficult decision to discontinue the course. Difficult because multi-faith education is something I believe in. The world needs more examples of these kinds of projects, not fewer. Difficult because I am ending 20 years of something I was very proud of, that impacted the lives of hundreds of students. But most difficult because I made a promise to Father Jack that in the end I could not fulfil.

How should I atone for not keeping my promise to my deceased friend? Jewish tradition covers this through the grand annulment of vows on the night of Yom Kippur called Kol Nidre. But what if the person who died was a Catholic priest and the Jewish rituals don’t feel sufficient? How can I honor someone from a different faith tradition in a way that honors my faith and theirs?

I have gone the way of confession. Both Jewish and Catholic traditions offer confession as a ritual, albeit in different ways. In Judaism we confess our sins through prayer, mostly on Yom Kippur, and mostly to G-d directly. In Catholicism, there is a human address to the confession—the Priest. No, I’ve not tried sitting in a booth in a church talking to a priest. Instead, I created something that felt authentic in the Jewish tradition as well. In the Hebrew month of Elul, the month before Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, Jewish custom urges us to seek forgiveness by approaching the people in our lives we have wronged—to have difficult conversations with the goal of offering apologies and asking forgiveness.

In the spirit of this tradition, to honor Father Jack, Dr. Ibrahim, and our class, I forged an atonement / confession ritual. I decided to seek out certain people who had a stake in this relationship and our course. I invited them to meet with me so that I could confess and ultimately apologize for not fulfilling my promise. In the past month, I have spoken with family members of both Dr. Ibrahim and Father Jack, as well as academic colleagues, including professors and deans from the University. I also spoke with several former students. Each person I spoke with has been extremely gracious and grateful for keeping the work and memory alive as long as I could.

I decided that if I could confess and apologize to ten people, the number that indicates a spiritual quorum in Judaism, the ritual would be complete. These confessions will not undo my own disappointment and sense of loss. Speaking to these witnesses, however, does offer me a release. With each person I speak to, the burden of guilt lessens and the script flips. I go from a sense of failure to keep a promise to a sense that the course, like the lives of my colleagues and friends, had come to its completion.

Sometimes enough is enough, even when it is not enough.