Forget about crises of faith, at least this week, and focus instead on crises of self-confidence. It’s not that faith in that which is beyond / above us is not important, but as we see in this week’s Torah reading, if you don’t believe in yourself, faith in that which is beyond yourself is flimsy at best. That seems to be something with which we all wrestle, be it us, the ancient Israelites, or even God.

Who hasn’t had moments when they lost faith in themselves and in their own ability to meet the moment in which they found themselves? I certainly have, and in my own defense, and in defense of all of us, I would suggest that to never experience such a crisis signals that we live in arrogance and lack in self-awareness. On the other hand, we should never be defined by those feelings. It leaves us easily manipulated by others and often making the worst decisions, both of which we see this week in the stories related in Parashat Sh’lakh.

Moses sends spies to scout out the Promised Land, and 10 of the 12 spies return saying that the land promises to destroy them. It is, they report, a land inhabited by giants who will make it impossible for the Israelites to ever dwell there. Accepting this report at face value, the people have a collective meltdown, panicking to the point of wishing that they had simply died in Egypt. But why? Why, after having been through so much together, and experiencing as many miracles as they had, was that their response?

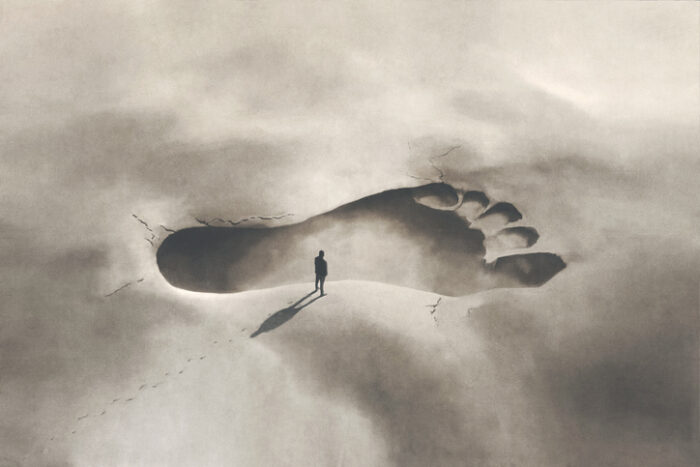

Despite the tangential suggestion found in Numbers 13:31 that their crisis was one of faith in God, the real crisis, as we see in verse 33, is not loss of faith in God, but a lack of confidence in themselves: “We seemed to ourselves as grasshoppers, and so, that is how we appeared to them [the inhabitants of the land].” And having projected out their own shabby sense of themselves onto others, they at once concluded that all was lost, at least for them. And in fact, it was, as this was the moment in which that entire generation consigned themselves to 40 years of wandering and then death in the desert, leaving inheriting the land to the next generation. Why? Because if we cannot see ourselves as rising to the challenges in our lives, there is extraordinarily little chance of our ever doing so.

To be fair, God plays a role as well, declaring that a generation defined by such a lack of confidence would never make it into the land of Israel. But God also seems to have a self-confidence problem, and I base my assertion both on how God views the Israelites’ problem, and, even more, based on how Moses is able to manipulate God’s response to the problem.

First, God ignores the peoples’ self-declared crisis in self-confidence, seeing it instead as a failure of faith in God. And as is so often the case, insisting on making things about ourselves, even when others assure us that it is not, reflects our own crisis of self-confidence. While theologians can quibble about what it means for God to have a crisis of self-confidence, this is hardly the first time it has happened in the Biblical story, so let’s accept that at the very least, if God can have such a crisis, we can too, and the real issue is what lessons can be learned from such moments and how we respond to them.

Second, when God lashes out, thinking the whole thing was about the Israelites’s lack of faith in “Him,” Moses is able to manipulate God, albeit in ways that evoke God’s mercy and forgiveness. Moses persuades God not to wipe out the people, that the nations of the world will see the destruction of the Israelites not as a failure of the Israelites, but as a failure of God.

God buys Moses’ argument and promises not to destroy the people, instead deferring the inheritance of the land to the next generation. Better than genocidal retribution, for sure, but only made possible by God’s concern with losing face in the eyes of the world. Here too, the interaction of Moses and God teaches that allowing others’ views of us to eclipse our own view of ourselves makes us lose control of our destiny.

As the story wraps up, we uncover two insights — one from the people and one from God —that can serve us all well. First is forgiveness. God not only accepts Moses’ argument, but forgives the people for their perceived rebellion. Only when we forgive the trespasses — real or imagined — against us can we fully recover control of our story. And second, that even with forgiveness there is a lasting cost to past crises. The people really cannot enter the land, even though they’ve come to want to. That die has been cast and there is no going back, even though they have been forgiven. Forgiveness, it seems, is not about undoing the past, but a part of the process through which we can create new futures — futures animated by greater appreciation of who we are and who others are as well. As much as faith in God can bolster our sense of self, it is often a healthy sense of self that creates the ability to have healthy faith in God.