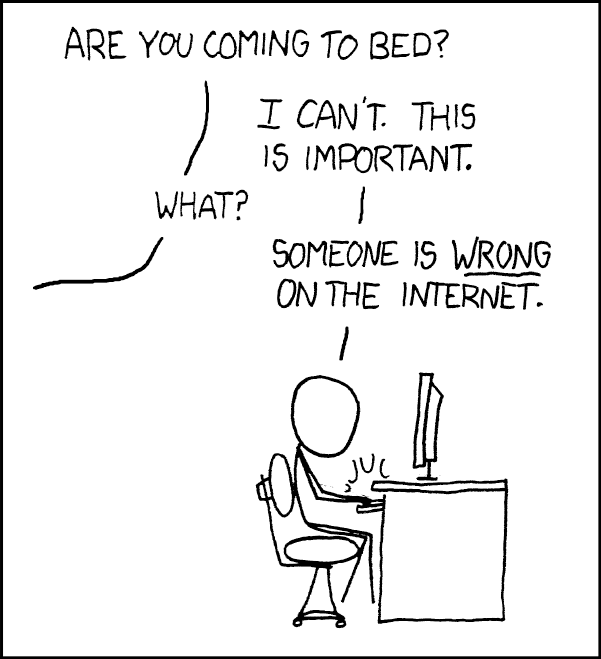

A now-classic cartoon from Randall Munroe, creator of the comic xkcd, shows a stick figure at his computer. Entitled “Duty Calls,” a disembodied voice yells out from another room, “Are you coming to bed?” “I can’t,” the figure responds. “This is important.” “What?” the voice asks. “Someone is wrong on the internet!”

As the internet and social media have evolved over the years, arguments have moved from encompassing not just facts, but values, as well. If it feels like social media feeds have become dominated by discourse about how awful an action, statement, or policy has been, that’s because moral indignation gets clicks and shares. Yes, funny memes, family photos, and thought-provoking articles do show up, but righteous anger gets rewarded online through its algorithms.

On one level, that sense of righteousness can be a positive. In this week’s double portion, Acharei Mot – Kedohsim, we find a list of rules of how we are to be a holy people. Many of the texts that inspire us, and have even become slogans, appear in Leviticus 19 – “Do not stand idly while your neighbor bleeds” (19:16), “Love your neighbor as yourself” (19:18), and “Do not insult the deaf or put a stumbling block before the blind” (19:14). Many of those texts have interpretation and rules surrounding them to help us move beyond these catchphrases to actionable items. After all, we need to think about who truly is our “neighbor,” both our responsibility and our safety if we see someone else in danger, and what knowledge we might have that would lead to a “stumbling block” in understanding.

When it comes to social media, one verse, in particular, needs careful consideration: “You shall not hate your kinsfolk in your heart. Reprove your kin but incur no guilt on their account.” (19:17) It may feel like the first part of this verse gives license for us to rebuke those who disagree with us, or to share our righteous anger – after all if we see someone acting immorally, we may feel like we have an obligation to say it.

But saying something isn’t the same as hearing it. In a Talmudic expansion of this verse, we are commanded to rebuke someone in a way that the other person can hear it, and in a way that it doesn’t embarrass them. Other commentators even say that it should be done in private – in direct contrast with how so many rebukes fly across our screens.

Psychology Professor Billy Brady recently arrived at this latest insight on how public rebuke and moral indignation may feel good, but is ultimately deeply ineffective in trying to change our public conversation:

[…R]eceiving positive feedback on “morally outraged” posts encourages people to express more moral outrage in the future. In short, people have social incentives to express outrage. These incentives—and norms—can lead people to exaggerate their expressions of outrage leading others to overestimate how morally outraged others actually are. This is all part of the outrage cycle that, in turn, leads others to generate exaggerated perceptions of hostility, ideological extremity, and polarization.

Without a doubt, there are policies – and even people – that deserve our rebuke and condemnation. But how we phrase it is key; we need to think about our goal and our audience. We humans have a tendency to seek reinforcement and affiliation, and castigating others is an easy way to build that sense of affiliation. But most of the time, it doesn’t actually change the conversation, it doesn’t lead to self-reflection, and it doesn’t cause someone to change their mind. Instead, it deepens our entrenchment and pulls us farther away from each other.

We can easily fall into the trap of wanting to be right – both factually and morally. But as the cartoon above reminds us, not only is that an unending task, it’s also counterproductive. It’s not so much what we say, but who we’re talking to, how we say it, and the goal of this communication. A general public rebuke will generate likes and shares, but a specific and private conversation will be so much more effective.

And sometimes, we simply need to give up on trying to change people’s minds, and just go to bed.