On Friday, we got new Chabad emissaries on our block. Yeshiva boys were assigned to walk our neighborhood in downtown Toronto and give us the weekly Torah newsletter. It’s a neighborhood with many liberal Jews, several small liberal synagogues and independent minyans, and no kosher bakeries or butchers. Last year’s two teenage boys, one from Massachusetts, learned quickly that our house was pretty well set with the Jewish practice we have. Their visits were mostly pleasant pre-Shabbat chats with my husband, who works from home. He speaks yeshivish from his own yeshiva days and usually has challah baking when they come.

This week, I was home too, and the new yeshiva boys were eager. This year’s are from Brooklyn. They brought Shabbes candles. They offered my husband to put on tefillin, which he politely declined. They tried to teach him what tzedakah was and offered him a coin to put in the pushke (tzedakah box), to which my husband confusedly clarified, “In your pushke or in ours?” gesturing to our pushke next to our Shabbes candlesticks on our buffet. Finally, they offered to blow the shofar. I called to the front door from my computer set up in the dining room, “Yes! Shofar, I’ll take.”

I stood and closed my eyes. The teen haltingly blew the shofar with some false starts. It was the first time I heard shofar this Elul — a month in which the shofar is traditionally blown every weekday morning after services. And finally, before he left, he said that during the pre-High Holidays month of Elul, the King is in the field.

This, too, I could appreciate. More than other times in the year, Elul and Tishrei encapsulate a particular journey with God, beginning in Elul and going through the High Holidays to the end of Sukkot. The Alter Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, wrote two hundred years ago about this time of Elul through a parable: When the King approaches his city, its inhabitants go to greet Him in the field, and it’s a time of greater access by common folk before the King gets back to the palace. There’s a developing texture of our relationship with God in these weeks, starting in the field and culminating in the palace. Out here in the field, even us shleppers can access God, where we live and work, in our everyday moments.

God is different out here in the field without the finery of the throne. Many Jews only encounter God of the throne room on Yom Kippur, one of the only Jewish traditions the majority of Jews today participate in. But these weeks before the High Holidays are an opportunity to wake up to God right here, outside the grocery store, when I have the choice of giving tzedakah to the woman who sits there every day. When my youngest throws a tantrum. Before sleep, when I ask forgiveness from my spouse. God in the field is the moments full of potential holiness every day, not just in once-a-year peak experiences.

Elul is a chance to hear the false starts, the unskilled sound of the shofar as each of us attempt to wake up. This is no time for perfected performance; it’s time for striving to be better, no matter how haltingly. “Wake up,” the shofar says. “Turn this life around and get back to what you were put on this earth to do.” God might be on the throne in the palace during Yom Kippur, but for the next two weeks, God is still here with us in the field as we toil.

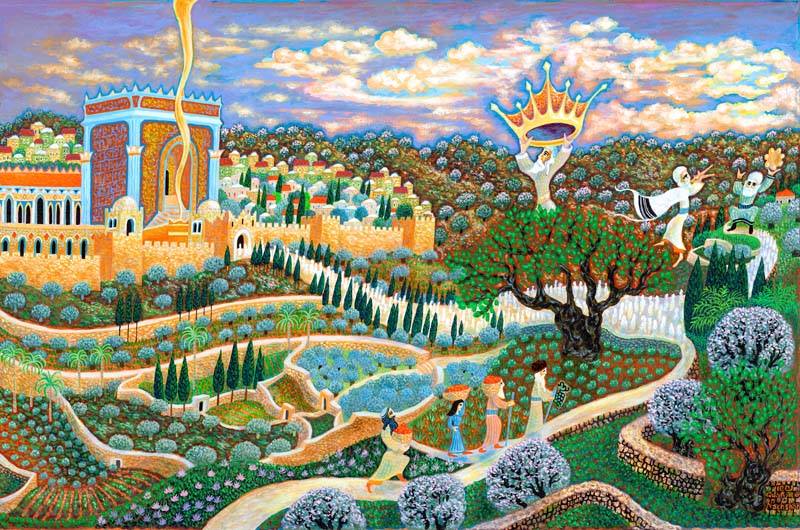

Artwork by Baruch Nachshon, nachshonart.com ©

Rabbi Julia Appel is Clal’s Senior Director of Innovation, helping Jewish professionals and lay leaders revitalize their communities by serving their people better. She is passionate about creating Jewish community that meets the challenges of the 21st century – in which Jewish identity is a choice, not an obligation. Her writing has been featured in such publications as The Forward, The Globe and Mail, and The Canadian Jewish News, among others.