Some things really are worth fighting for. Everyone believes that, especially when we include the fact that one can fight without using violence. The fight for free speech is often — though not always — one of the areas where that is most true.

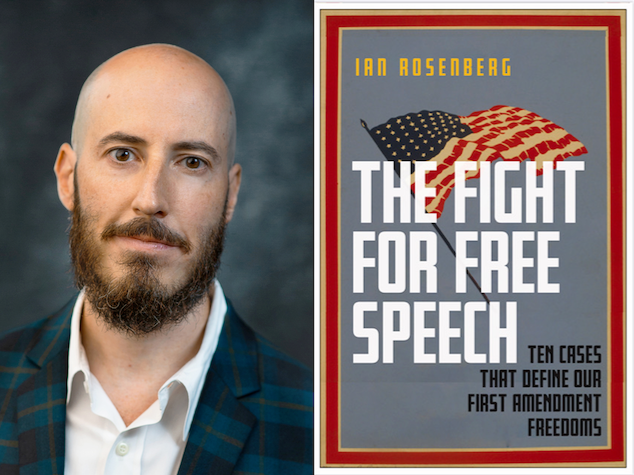

And while some combatants are good individual fighters, others — leaders — often shine most brightly by virtue of both leading by example, and by preparing others to enter the fray as well. Ian Rosenberg falls into the latter category, as demonstrated by his new book, The Fight For Free Speech, Ten Cases That Define Our First Amendment Freedoms. We sat down for a very interesting conversation, and I invite you to join us here, now.

Ecclesiastes 12:12 warns us that “To the making of books, there is no end,” suggesting that maybe it’s enough already with so many books and so much book-making, especially as some argue that among the central challenges we currently face is not that we have too little information, but too much. So, let me start by asking you — one author to another — why another book at this time, and what, if any, of Ecclesiastes’ concerns accompanied you in the making of this one?

The genesis of The Fight for Free Speech came after the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. I was talking to my family at the dinner table about the news report I was reviewing, as part of my job as a media lawyer, on the student survivors turned activists. My children (at the time ages twelve and ten) became very serious about what would happen if they left school during the day to join the National School Walkout protests. Could they be punished? What were their rights? Americans of all ages are confronted with increasing frequency by a barrage of free speech questions like these, and yet there hasn’t been a general-interest book explaining our First Amendment rights published in more than a decade. So that led me to write The Fight for Free Speech which is a user’s guide for understanding our free speech freedoms.

The strikingly contemporary focus of The Fight for Free Speech also sets it apart from other popular works on the First Amendment. Most classics in this field were written in a time before our speech landscape was radically altered by the internet and social media era in which we now live. In contrast, each chapter of The Fight for Free Speech begins with the exploration of a free speech dilemma that is plucked from the headlines of only the past few years. As a result, my book not only covers new territory but also conveys the pressing urgency of why Americans need this book now.

You state upfront, your belief, contrary to what is taught in most law schools, that “everyone can have a practical working knowledge of free speech law.” Why is that important, and why is it especially important now?

As President Biden has said, “democracy is fragile.” And I think if this past year has shown us anything–from election coverage to the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, to reporting on Covid– it’s that democracy is in danger unless vital information comes to light from protestors and the press. In The Fight for Free Speech, I explain why Collin Kaepernick should have the right to take a knee, why the press is allowed to publish top secret documents even during war time, how students have a right to protest in school, and I believe all of these stories are valuable because they give people the information they need to exercise their rights and support democracy. There’s also a story that Justice Souter liked to tell about Benjamin Franklin, who was asked “shortly after the 1787 constitutional convention adjourned, what kind of government the constitution would give us if it was adopted.” Franklin’s wise reply was, “A republic, if you can keep it.” Souter then cautioned, “you can’t keep it in ignorance.” We can’t hope to keep our democracy alive if citizens remain uninformed of our First Amendment rights and history. So I believe that The Fight for Free Speech can be a handbook for combating authoritarianism, protecting our democracy, and bringing an understanding of free speech law to all.

In that same introduction, you contend that “wisdom can be condensed without being dumbed down.” What is the difference, for you, between the “knowledge” you mentioned above, and “wisdom?”

I think that The Fight for Free Speech will give people the knowledge they need from the past about our First Amendment rights. But even more importantly I hope that through the stories in this book that people will gain the wisdom– the ability to put knowledge in context and to exercise good judgment– to advocate for free speech as a grassroots activity in the future.

The book is built around ten fascinating cases, and while I know that it may be akin to picking your favorite child, or at least your favorite movie, which of the ten is the one you think we most need to examine now, and why that one?

As a Jew, I think the most difficult chapter for me to write, and one of the most important, concerns the tragic Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, and those events are what start off my chapter entitled Nazis in Charlottesville, Funeral Protests and Speakers We Hate. Because in the aftermath of Charlottesville, the question facing us with renewed urgency is: must the First Amendment protect what is often called “hate speech?” I examine the case of Snyder v. Phelps, which involves the fringe Westboro Baptist Church taunting the families of dead soldiers at military funerals. In this 2011 decision, Chief Justice Roberts reiterated the court’s commitment to holding that the First Amendment does protect hate speech. He wrote that “Speech is powerful. It can stir people to action, move them to tears of both joy and sorrow, and–as it did here–inflict great pain. … [But] we cannot react to that pain by punishing the speaker.” And I agree that this is the right decision from a consistent First Amendment perspective because the most difficult problem with any attempt to regulate hate speech is “Who decides?” But at the same time, I am still troubled about what this means for our country, and most particularly for minorities who have faced systemic oppression in our society. This is definitely one of the most pressing free speech topics facing us today, and it’s also a key example of a situation where even if you want to change what the law protects, Americans need to start by knowing what the law is, and how the Supreme Court approaches hate speech, as a first step.

Which of the ten cases leaves you with the most questions, or the least sense, or the least sense of resolution?

I begin my chapter on social media speech, with Sacha Baron Cohen (aka Borat), who gave a powerful speech to the Anti-Defamation League in 2019, warning that “Our pluralistic democracies are on a precipice … and the role of social media could be determinant.” And I think he might well be right. However, this is an area where the Supreme Court is really late to the game. Their only significant decision on social media and free speech came in 2017. And in this case, Packingham, Justice Kennedy acknowledged it’s now clear that the most important place “for the exchange of views, today… is cyberspace–the vast democratic forums of the Internet in general, and social media in particular.” So at this stage, the court is granting full free speech protection to social media. What is not clear is what can be done to mitigate the problems created by social media–whether it’s trolls and hate mobs on Twitter or how to combat Nazi propaganda on Facebook. Although the Court doesn’t have easy answers for us on the question of social media, I do believe The Fight for Free Speech can help provide Americans with guidance on how to approach these issues within a First Amendment framework. The future of free speech is certainly online. How we seek to chart that future can only begin by taking in and learning from our First Amendment stories of the past.

At the end of the book, you offer what I would describe as a five-point compass that we can use as we chart the healthiest possible course for the future of free speech. What are those five points, and why did you choose them?

Most of The Fight for Free Speech is more descriptive than prescriptive. But as advice for how to consider future free speech controversies, my recommended maxims are:

- Protect Dissent

- Defend the Press

- Resist Government Speech Restrictions

- Expand the Marketplace of Ideas

- Allow Speakers to Express Messages How They Choose

While these lines don’t encapsulate all of the ideas behind our free speech rights today, I believe they are uniquely beneficial for guiding us in the years to come.

My experience is that writing a book changes the writer in all sorts of ways — large and small. How has writing this book changed you?

My wife has run marathons, and because I’m not a runner (or even someone who likes sports), I thought I would never know what it is like to face that kind of challenge. I had always wanted to write a book, and for a long time I’ve been thinking about writing this book, but even though I knew I had a lot to say and great stories to tell, I wasn’t entirely sure until the very end that I would actually be able to write the whole thing and finish it! For me, writing The Fight for Free Speech over the course of the last three years has given me an incredible sense of accomplishment that I think might be akin to finishing such an epic 26.2-mile race.

What’s next for you? What big project is taking up the time and energy that went into the making of this book?

I’m excited to let your readers know that my next project is a graphic novel adaptation of this book. It will be called Free Speech Handbook, and it will be coming out in September from First Second, an imprint of Macmillan, as part of their new World Citizen Comics series, that focuses on civics education and includes other adaptations like Dan Rather’s memoir as well. The incredible illustrations in Free Speech Handbook are by Eisner-nominated artist Mike Cavallaro, and they provide a uniquely exciting new dimension to these stories and free speech metaphors.

About what have I not asked you, but you wish I had?

I love talking about one of the characters in the first chapter of The Fight for Free Speech because I think she’s a relatively unsung, Jewish, feminist hero. Her name is Mollie Steimer. She fled the Russian pogroms and immigrated to the US in 1933 at age sixteen. She worked in a garment factory to support her family, and her life of struggle radicalized her. She became an anarchist. Emma Goldman said she had “an iron will and a tender heart.” Mollie tossed leaflets from the window of a factory on the Lower East Side that criticized the government for sending US troops to Russia during WWI and ended up sentenced to fifteen years in prison for sedition. It was her case (called Abrams v. US, 1919) that brought about a dissenting opinion by Justice Holmes that introduced the marketplace of ideas metaphor, which completely redefined free speech protections for protestors. And so Mollie’s actions lead the Court to ultimately recognize the First Amendment right to criticize the government and even advocate for illegal action (unless it likely causes imminent harm). It’s the beginning of modern free speech in America, and a lot of that is thanks to Mollie.

Listed for many years in Newsweek as one of America’s “50 Most Influential Rabbis” and recognized as one of our nation’s leading “Preachers and Teachers,” by Beliefnet.com, Rabbi Brad Hirschfield serves as the President of Clal–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a training institute, think tank, and resource center nurturing religious and intellectual pluralism within the Jewish community, and the wider world, preparing people to meet the biggest challenges we face in our increasingly polarized world.

An ordained Orthodox rabbi who studied for his PhD and taught at The Jewish Theological Seminary, he has also taught the University of Pennsylvania, where he directs an ongoing seminar, and American Jewish University. Rabbi Brad regularly teaches and consults for the US Army and United States Department of Defense, religious organizations — Jewish and Christian — including United Seminary (Methodist), Yeshivat Chovevei Torah (Modern Orthodox) Luther Seminary (Lutheran), and The Jewish Theological Seminary (Conservative) — civic organizations including No Labels, Odyssey Impact, and The Aspen Institute, numerous Jewish Federations, and a variety of communal and family foundations.

Hirschfield is the author and editor of numerous books, including You Don’t Have To Be Wrong For Me To Be Right: Finding Faith Without Fanaticism, writes a column for Religion News Service, and appears regularly on TV and radio in outlets ranging from The Washington Post to Fox News Channel. He is also the founder of the Stand and See Fellowship, which brings hundreds of Christian religious leaders to Israel, preparing them to address the increasing polarization around Middle East issues — and really all currently polarizing issues at home and abroad — with six words, “It’s more complicated than we know.”