Growing up, I was terrified of two things: being sent to the local Children’s Home (something my mother assured me would happen if I didn’t behave myself) and ending up in an iron lung. That I was afraid of the latter was a little neurotic, given that the Iron Lung went out of fashion after the polio vaccine was developed in the late 1950’s. Still, I’d seen a documentary about polio at school and, oblivious to the fact that it was historical, got it into my head that ending up in an iron lung was a real possibility.

Of course, had I been born a few decades earlier, my fear would’ve have been well founded; the iron lung was, without doubt, one of the most ominous medical contraptions ever invented. At least, I thought so, until I took the time to research its history and use; wherein I discovered that it deserves the honor of being one of the most wonderful medical contraptions ever invented; wonderful, because it saved the lives of thousands of people – mostly children, and was a crucial step in the development of modern-day respirators, which have saved 100’s of thousands.

Poliomyelitis (collq. polio)

Although the iron lung was not used exclusively in cases of polio, it is certainly the disease most commonly associated with it, and was the impetus behind its invention, continued development and mass production.

Polio (aka. Infantile Paralysis) is a highly contagious disease caused by the polio virus; it has a fecal to mouth transmission, and is usually contracted through contaminated water and/or food. It flourishes in warm weather and, when endemic, can rapidly spread through an entire population.

Humans produce natural antibodies to the polio virus, so it usually makes it no further than the digestive system. However, when antibody production is impeded due to a comprised immune system or poor nutrition, the virus can make its way into the bloodstream and central nervous system. Once the virus attacks the CNS, dysfunction and paralysis of the muscles occurs – usually in the extremities (fancy for arms and legs) and, in severe cases, the neck and chest.

As with most viruses, polio peaks and then subsides. If a patient can withstand the peak period – typically 2-3 weeks – then the chance of survival is high; however, the damage to their muscular system – ranging from mild to catastrophic – can last a lifetime.

[There is much more that can be said about polio – its history, spread and impact on the world; not to mention the fight to find a vaccine (a fascinating story itself, one filled with intrigue, acrimony, conspiracy, failure and success). However, this article focuses specifically on the iron lung and its role in – while not stopping – at least impeding the devastation caused by polio in America and other countries in the first half of the 20th century.]

Invention

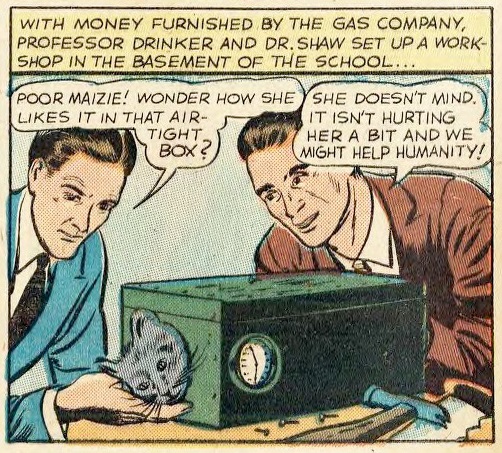

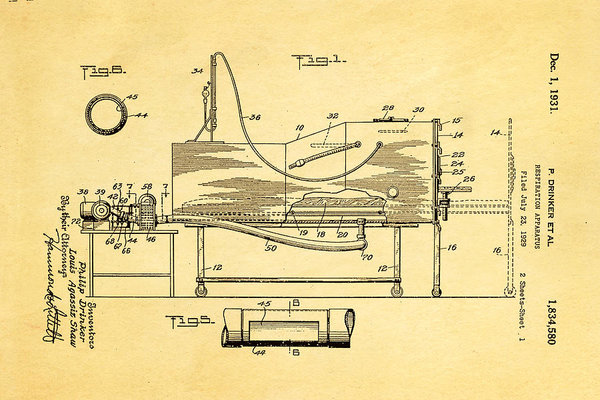

The iron lung was the brain child of Professor Philip Drinker (1894-1972) and Dr. Louis Agassiz Shaw(1886-1940) of Harvard Medical School. Necessity being the mother of invention, Drinker and Shaw were intent on developing a machine that could breathe for a person who was no longer capable of breathing for themselves – a potential consequence of polio. Funded by a Gas Company in New York – keen to find a solution for respiratory failure caused by coal-gas poisoning – the pair set about constructing a negative pressure ventilation chamber that could expand and contract the chest, thereby simulating breathing by drawing air into the lungs as the chamber pressure dropped, and forcing air out of the lungs as the pressure rose. A similar ventilator, based on the same principle, had been invented in 1670 by British scientist, John Mayow (1640-79); however, it never went into production, nor gained the notoriety of its American descendent.

Drinker and Shaw fashioned a metal box into an airtight chamber, hooked it up to a vacuum cleaner, and stuck in a cat. The cat fared well in their negative pressure ventilator, and the pair were convinced of its effectiveness.

The first human test took place at Boston Children’s hospital on October 12, 1928. The testee was an 8-year-old polio sufferer on the verge of death due to respiratory failure. Once encased in the iron lung, the young patient’s breathing rapidly improved; sadly, however, she died 5 days later of heart failure – the polio virus having also damaged her heart muscles. Despite proving capable of keeping a person alive in the event of respiratory failure, the death of its first test subject initially consigned the iron lung to a warehouse.

Soon after, however, a Boston Doctor, in a desperate bid to keep a polio-stricken Harvard student alive, contacted Professor Drinker and asked to use his iron lung. This time it was a success. Breathing for the young man during his period of respiratory paralysis, and afterwards as his chest muscles healed and strengthened, the iron lung, having plucked him from the brink of death, was deservedly hailed a miracle. Professor Drinker was deemed a hero, and his iron lung quickly went into production.

Controversy

As with most revolutionary inventions, the iron lung was not without controversy. A contemporary of Drinker’s, Inventor John Haven Emerson (1906-97), impressed with the lifesaving qualities of the iron lung, set about making some modifications – changing the motor, adding portal holes so medical staff could both see and access the patient, and installing a sliding bed, making it easier to get a patient in and out of the chamber.

That Emerson’s tinkering had vastly improved the iron lung was undeniable, not only was it quieter and lighter and more attractive (well, as attractive as a giant metal lung can be), it was also cheaper to produce. Drinker was having none of it, he thought Emerson was trying to get in on what was proving to be a lucrative business, and sued him for patent infringement. Emerson argued that a lifesaving device like the iron lung should be free to humanity; besides which, as he correctly pointed out, Drinker had nicked the idea off John Mayow. The court agreed with Emerson, and Drinker’s patent was torn up, leaving him to share the glory and profits with his invention-infringing nemesis.

Mass Production

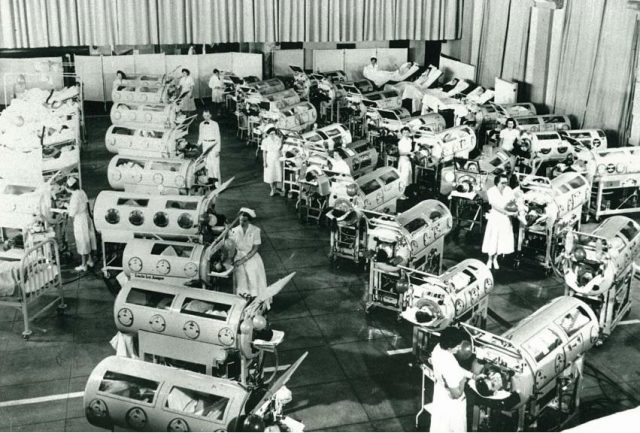

Drinker and Emerson’s squabbling was neither here nor there when the next wave of polio hit America and continued, unabated, for the next 3 decades, until the polio vaccine was developed. During this time, the only thing that stood between a polio-ravaged respiratory system and certain death, was the iron lung. Not that everyone who went into an iron lung, came out alive; if polio attacked the heart or brain stem, there was little chance of survival. Still, the iron lung saved many who would otherwise have died from respiratory failure, making them standard medical apparatus in most hospitals, and certainly in all major ones; some hospitals having wards full of them.

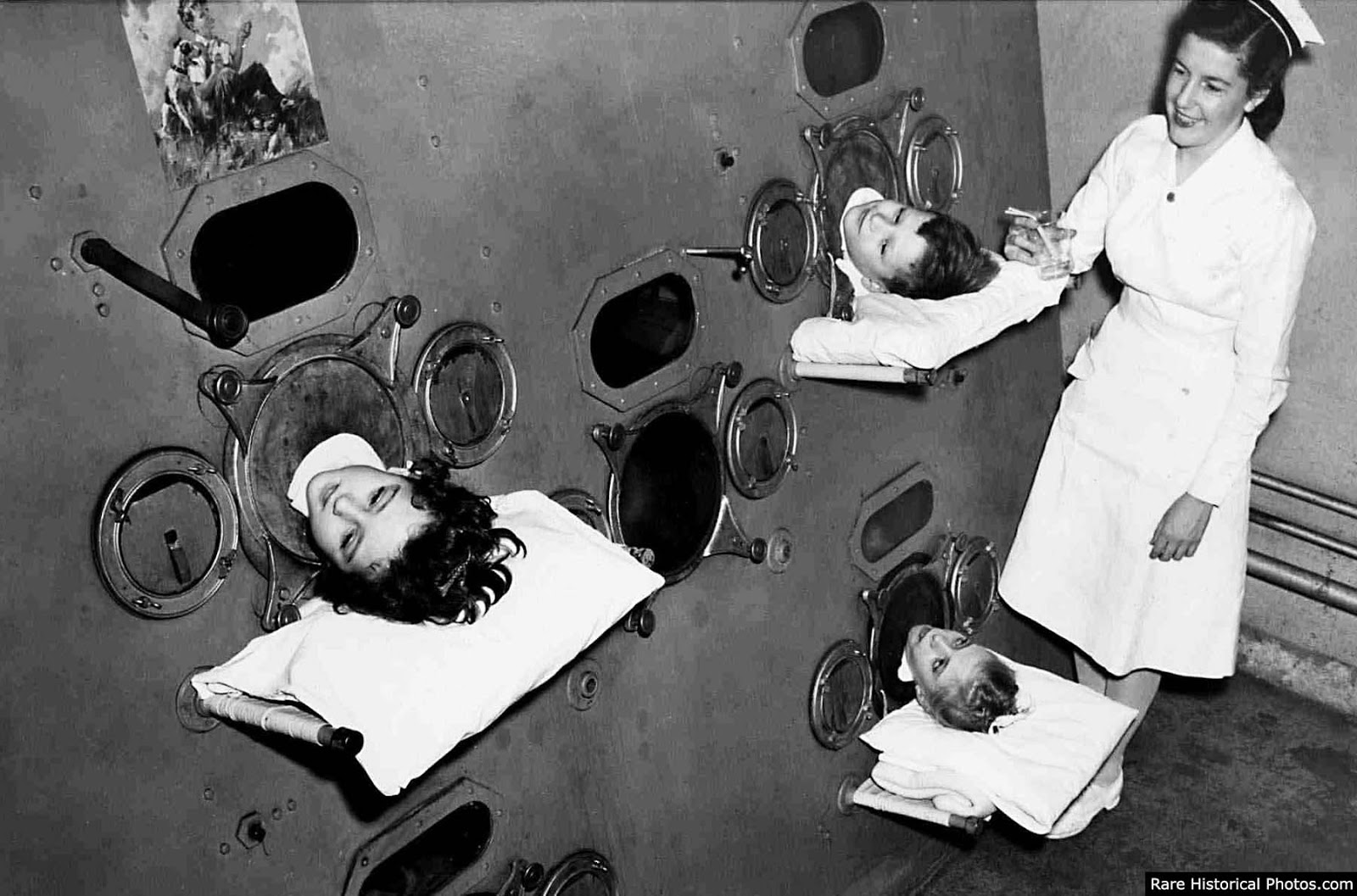

Further modifications to the iron were made over time, to improve its overall working and increase the comfort of patients. The most remarkable variant was a multi-storied, multi-occupant iron lung, which was big enough for hospital staff to stand up in.

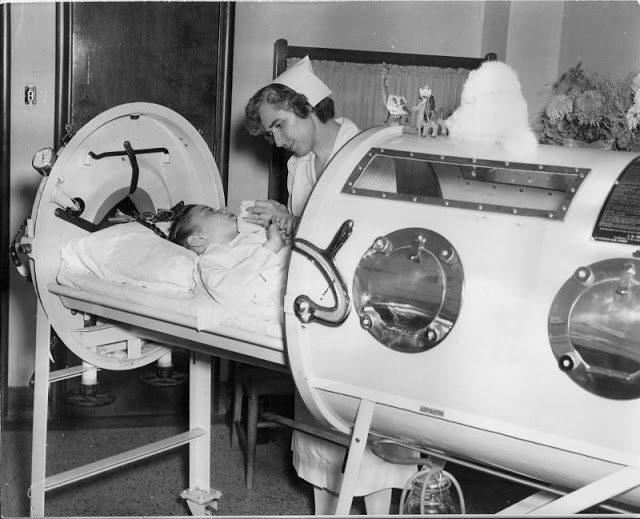

And saddest of all was the pediatric iron lung, the forerunner of the incubator.

March of Dimes

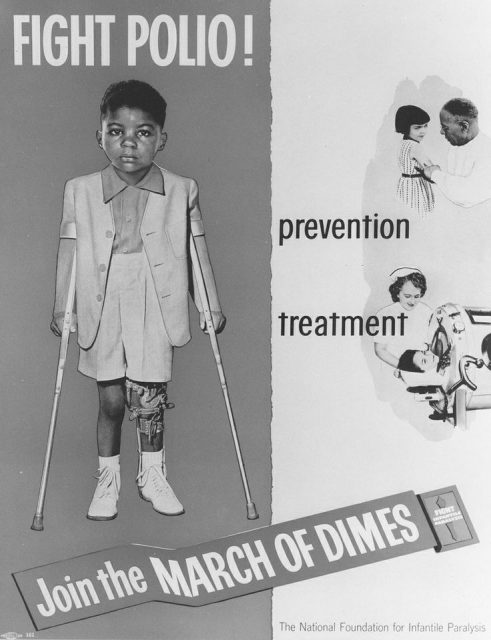

Even with the new modifications, iron lungs were expensive to produce and use; as was the rehabilitation necessary to bring an afflicted patient back to a semblance of health. Hitherto, hospitals and health services relied on the patronage of the wealthy few. But when polio afflicted the White House, all that changed.

Although polio’s primary target was young children, it could, in fact, strike a person at any age. One such adult sufferer of polio was the 32nd President of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who contracted the disease in 1921 at the age of 30, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down. In 1938, Roosevelt established The National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, to fight the war on polio. Rather than seek large contributions from wealthy individuals, the Foundation asked the public to make a small donation – a dime to be specific – in an annual drive, known as the March of Dimes.

It was a wildly successful campaign, raising millions for the cause, and ensuring hospitals were fitted out with polio paraphernalia – including iron lungs – and making rehabilitation resources available. Most importantly, it funded the fight for, and eventual development and distribution of, the polio vaccine.

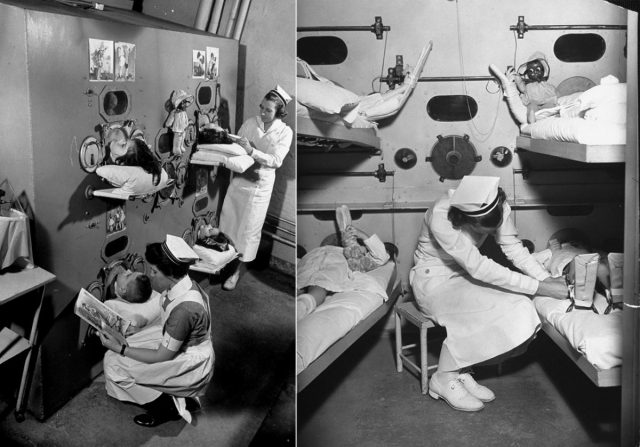

Life in an iron lung

Life in an iron lung was far from comfortable. With the head essentially detached from the body, all a person could do was breathe, speak and look around the room, with the aid of an angled mirror attached above the head. All bodily functions had to be taken care of by someone else, from eating to waste elimination. Bedsores were a common problem and, necessarily, mind-numbing boredom. Typically, a patient with respiratory difficulties would spend anywhere from a few days to a few weeks in an iron lung; although sometimes their encapsulation stretched on for months and, in very rare cases, years.

Thankfully, by the 1960’s, the iron lung was replaced by positive pressure ventilators – antecedents of the ventilators we see today – which push air into the lungs, and have the added advantage of not encasing the patient in iron, allowing for freedom of movement. Nonetheless, some people remained in their iron lungs long after they became obsolete in standard medical practice.

One such person was Dr Martha Mason (1937-2009), of Lattimore, North Carolina, who spent 61 years in an iron lung, from the time she contradicted polio at age of 11, until her death. Unbelievable as it may seem, Dr Mason lived a full and rewarding life despite her iron encasement; indeed, precisely because of her limitations, she developed a rich life of mind, earning a bachelor’s degree in English and an honorary doctorate. She was intelligent and erudite and insatiably curious about life. She loved and learned and grew as person, and was excellent company for her friends and academic peers who were devoted to her. She wrote a book about her life called: Breath: Life in the Rhythm of an Iron Lung, which is as fascinating as it is inspiring.

It is because of Dr Mason that I have been able to relinquish my fear of the iron lung, and come to regard it as the medical marvel and lifesaving device it was to many. And, in relinquishing that fear, I learned a valuable lesson about the nature of fears we gain through misunderstanding, and continue to nurse in our ignorance. The iron lung is not the macabre symbol of a devastating disease I thought it was; rather, it is a symbol of the human drive to preserve life and ease the suffering of others. And for that, it is wonderful.

Sources:

Mason, M. (2003) Breath: Life in the Rhythm of an Iron Lung, Down Home Press, USA

Pearson, D (1956) Iron Lung Documentary, Milton Hammer, Capital Hill Studios, Washington DC

(2004) Martha Mason Documentary, Gardner-Webb University, North Carolina

Photos 2, 3 & 4 Rare Historical Photos

Comic Comics with Problems

Rebecca is a painter, collage artist and writer. Originally from New Zealand, she now lives on a little Island in the Irish Sea. She has a degree in Religious Studies and is passionate about religious history, philosophy and esoteric goings on. Her favourite research topic is peculiar religious figures; those people who, through their devotion and vision of the divine, challenged the religious establishments to which they belonged, sometimes being crushed by those establishments, other times irrevocably changing them.

You can contact her and/or find her artwork and other writing on her website rebeccaodessa.com